[This piece was originally posted on 10 April 2017.]

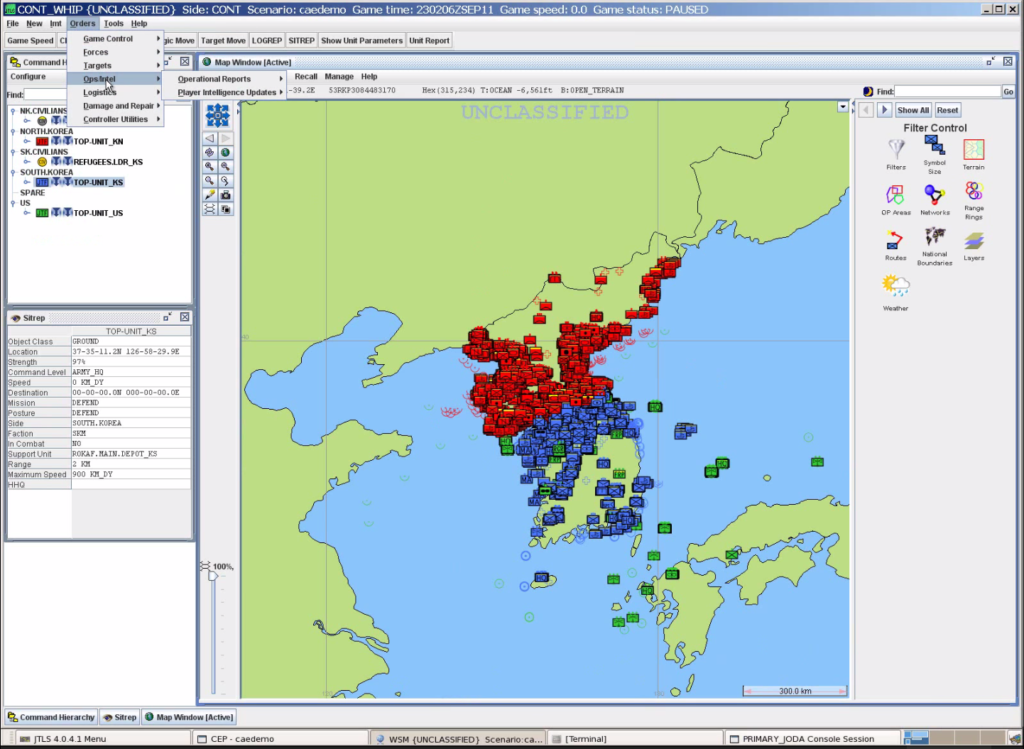

As the U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps work together to develop their joint Multi-Domain Battle concept, wargaming and simulation will play a significant role. Aspects of the construct have already been explored through the Army’s Unified Challenge, Joint Warfighting Assessment, and Austere Challenge exercises, and upcoming Unified Quest and U.S. Army, Pacific war games and exercises. U.S. Pacific Command and U.S. European Command also have simulations and exercises scheduled.

A great deal of importance has been placed on the knowledge derived from these activities. As the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command recently stated,

Concept analysis informed by joint and multinational learning events…will yield the capabilities required of multi-domain battle. Resulting doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership, personnel and facilities solutions will increase the capacity and capability of the future force while incorporating new formations and organizations.

There is, however, a problem afflicting the Defense Department’s wargames, of which the military operations research and models and simulations communities have long been aware, but have been slow to address: their models are built on a thin foundation of empirical knowledge about the phenomenon of combat. None have proven the ability to replicate real-world battle experience. This is known as the “base of sand” problem.

A Brief History of The Base of Sand

All combat models and simulations are abstracted theories of how combat works. Combat modeling in the United States began in the early 1950s as an extension of military operations research that began during World War II. Early model designers did not have large base of empirical combat data from which to derive their models. Although a start had been made during World War II and the Korean War to collect real-world battlefield data from observation and military unit records, an effort that provided useful initial insights, no systematic effort has ever been made to identify and assemble such information. In the absence of extensive empirical combat data, model designers turned instead to concepts of combat drawn from official military doctrine (usually of uncertain provenance), subject matter expertise, historians and theorists, the physical sciences, or their own best guesses.

As the U.S. government’s interest in scientific management methods blossomed in the late 1950s and 1960s, the Defense Department’s support for operations research and use of combat modeling in planning and analysis grew as well. By the early 1970s, it became evident that basic research on combat had not kept pace. A survey of existing combat models by Gary Shubik and Martin Brewer for RAND in 1972 concluded that

Basic research and knowledge is lacking. The majority of the MSGs [models, simulations and games] sampled are living off a very slender intellectual investment in fundamental knowledge…. [T]he need for basic research is so critical that if no other funding were available we would favor a plan to reduce by a significant proportion all current expenditures for MSGs and to use the saving for basic research.

In 1975, John Stockfish took a direct look at the use of data and combat models for managing decisions regarding conventional military forces for RAND. He emphatically stated that “[T]he need for better and more empirical work, including operational testing, is of such a magnitude that a major reallocating of talent from model building to fundamental empirical work is called for.”

In 1991, Paul K. Davis, an analyst for RAND, and Donald Blumenthal, a consultant to the Livermore National Laboratory, published an assessment of the state of Defense Department combat modeling. It began as a discussion between senior scientists and analysts from RAND, Livermore, and the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) sponsored an ensuing report, The Base of Sand Problem: A White Paper on the State of Military Combat Modeling.

Davis and Blumenthal contended

The [Defense Department] is becoming critically dependent on combat models (including simulations and war games)—even more dependent than in the past. There is considerable activity to improve model interoperability and capabilities for distributed war gaming. In contrast to this interest in model-related technology, there has been far too little interest in the substance of the models and the validity of the lessons learned from using them. In our view, the DoD does not appreciate that in many cases the models are built on a base of sand…

[T]he DoD’s approach in developing and using combat models, including simulations and war games, is fatally flawed—so flawed that it cannot be corrected with anything less than structural changes in management and concept. [Original emphasis]

As a remedy, the authors recommended that the Defense Department create an office to stimulate a national military science program. This Office of Military Science would promote and sponsor basic research on war and warfare while still relying on the military services and other agencies for most research and analysis.

As a remedy, the authors recommended that the Defense Department create an office to stimulate a national military science program. This Office of Military Science would promote and sponsor basic research on war and warfare while still relying on the military services and other agencies for most research and analysis.

Davis and Blumenthal initially drafted their white paper before the 1991 Gulf War, but the performance of the Defense Department’s models and simulations in that conflict underscored the very problems they described. Defense Department wargames during initial planning for the conflict reportedly predicted tens of thousands of U.S. combat casualties. These simulations were said to have led to major changes in U.S. Central Command’s operational plan. When the casualty estimates leaked, they caused great public consternation and inevitable Congressional hearings.

While all pre-conflict estimates of U.S. casualties in the Gulf War turned out to be too high, the Defense Department’s predictions were the most inaccurate, by several orders of magnitude. This performance, along with Davis and Blumenthal’s scathing critique, should have called the Defense Department’s entire modeling and simulation effort into question. But it did not.

The Problem Persists

The Defense Department’s current generation of models and simulations harbor the same weaknesses as the ones in use in the 1990s. Some are new iterations of old models with updated graphics and code, but using the same theoretical assumptions about combat. In most cases, no one other than the designers knows exactly what data and concepts the models are based upon. This practice is known in the technology world as black boxing. While black boxing may be an essential business practice in the competitive world of government consulting, it makes independently evaluating the validity of combat models and simulations nearly impossible. This should be of major concern because many models and simulations in use today contain known flaws.

Some, such as Joint Theater Level Simulation (JTLS), use the Lanchester equations for calculating attrition in ground combat. However, multiple studies have shown that these equations are incapable of replicating real-world combat. British engineer Frederick W. Lanchester developed and published them in 1916 as an abstract conceptualization of aerial combat, stating himself that he did not believe they were applicable to ground combat. If Lanchester-based models cannot accurately represent historical combat, how can there be any confidence that they are realistically predicting future combat?

Others, such as the Joint Conflict And Tactical Simulation (JCATS), MAGTF Tactical Warfare System (MTWS), and Warfighters’ Simulation (WARSIM) adjudicate ground combat using probability of hit/probability of kill (pH/pK) algorithms. Corps Battle Simulation (CBS) uses pH/pK for direct fire attrition and a modified version of Lanchester for indirect fire. While these probabilities are developed from real-world weapon system proving ground data, their application in the models is combined with inputs from subjective sources, such as outputs from other combat models, which are likely not based on real-world data. Multiplying an empirically-derived figure by a judgement-based coefficient results in a judgement-based estimate, which might be accurate or it might not. No one really knows.

Potential Remedies

One way of assessing the accuracy of these models and simulations would be to test them against real-world combat data, which does exist. In theory, Defense Department models and simulations are supposed to be subjected to validation, verification, and accreditation, but in reality this is seldom, if ever, rigorously done. Combat modelers could also open the underlying theories and data behind their models and simulations for peer review.

The problem is not confined to government-sponsored research and development. In his award-winning 2004 book examining the bases for victory and defeat in battle, Military Power: Explaining Victory and Defeat in Modern Battle, analyst Stephen Biddle noted that the study of military science had been neglected in the academic world as well. “[F]or at least a generation, the study of war’s conduct has fallen between the stools of the institutional structure of modern academia and government,” he wrote.

This state of affairs seems remarkable given the enormous stakes that are being placed on the output of the Defense Department’s modeling and simulation activities. After decades of neglect, remedying this would require a dedicated commitment to sustained basic research on the military science of combat and warfare, with no promise of a tangible short-term return on investment. Yet, as Biddle pointed out, “With so much at stake, we surely must do better.”

[NOTE: The attrition methodologies used in CBS and WARSIM have been corrected since this post was originally published per comments provided by their developers.]

With the December 2018 update of the U.S. Army’s Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) concept, this seems like a good time to review the evolution of doctrinal thinking about it. We will start with the event that sparked the Army’s thinking about the subject: the 2014 rocket artillery barrage fired from Russian territory that devastated Ukrainian Army forces near the village of Zelenopillya. From there we will look at the evolution of Army thinking beginning with the initial draft of an operating concept for Multi-Domain Battle (MDB) in 2017. To conclude, we will re-up two articles expressing misgivings over the manner with which these doctrinal concepts are being developed, and the direction they are taking.

With the December 2018 update of the U.S. Army’s Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) concept, this seems like a good time to review the evolution of doctrinal thinking about it. We will start with the event that sparked the Army’s thinking about the subject: the 2014 rocket artillery barrage fired from Russian territory that devastated Ukrainian Army forces near the village of Zelenopillya. From there we will look at the evolution of Army thinking beginning with the initial draft of an operating concept for Multi-Domain Battle (MDB) in 2017. To conclude, we will re-up two articles expressing misgivings over the manner with which these doctrinal concepts are being developed, and the direction they are taking.