The 36th Panzer Regiment was the tank component of the 14th Panzer Division, which had been destroyed at Stalingrad. When recreated, the division was supposed to have a three-battalion panzer regiment. However, it only received the I. and III. battalions before transferring to the eastern front in the autumn 1943. As losses accumulated, its remaining tanks and assault guns were concentrated in the III. battalion and the I. battalion was sent out of the theatre to replenish.

On 1 January 1944, the regiment had the following vehicles operational: 10 StuG, 11 Pz III, 11 Pz IV. In short term repair were: 7 StuG, 1 Pz III and 8 Pz IV. However, there is some uncertainty regarding the Pz III tanks, as they are not to be found in the organization chart, except for 6 command tanks in the battalion and the regiment. This is according to the monthly report to the Inspector-General of Panzer Troops (BA-MA RH 10/152).

The battalion war diary can be found in file BA-MA RH39/380. It is not as detailed as the war diary I have used for previous posts on I./Pz.Rgt. 26 Panther battalion. It just contains a narrative and I don’t have the kind of detailed annexes included in the file on I./Pz.Rgt. 26.

From the war diary, I conclude the following losses during January 1944:

StuG: 10 complete losses. One of them was only damaged by enemy fire, but could not be recovered due to nearby enemy units and was fired upon by other German StuG until it caught fire. Another 10 StuG were damaged, either by enemy fire or suffered from technical breakdowns.

Pz IV: 3 complete losses, 6 damaged. As there has been some posts on the effectiveness of artillery versus armour on the blog, it can be worth mentioning that one of the damaged Pz IV was hit by artillery fire.

Pz III tanks are not mentioned at all in the battalion war diary.

There are two comments on repairs in the war diary. On 14 January, it is said that one repaired tank returns and on 27 January, it is reported that 3 Pz IV and 1 StuG returns from workshops. However, this can not be all repairs. On 1 February, the battalion had 5 operational Stug and 2 in short term repair. As it started out with 10+7 StuG, had 5+2 on 1 February, while reporting 10 destroyed and 10 damaged during January, there must have been more repairs. The figures would suggest that 15 StuG were repaired, as there were no shipments of new StuG from the factories, according to the records in BA-MA RH 10/349 (list of deliveries of new AFV). Neither is any transfer of AFV from other units mentioned in the war diary.

It seems that the number of repaired Pz IV is 5, given the number on hand on 1 February.

All in all, this would mean that the battalion started out with 10 StuG and 11 Pz IV on 1 January, lost irretrievably 10 StuG and 3 Pz IV, 10 StuG damaged and 6 Pz IV damaged, while 15 StuG and 5 Pz IV were repaired. It should be noted that these figures are less certain than those given for the I./Pz.Rgt. 26 in previous posts, as the war diary of the III./Pz.Rgt 36 is not as detailed.

Admittedly, it is problematic to compare loss rates between units fighting different enemy formations, but it is still tempting to compare the III./Pz.Rgt. 36 with the I./Pz.Rgt. 26. After all, they fought in the same general area (Ukraine south of Kiev) in similar conditions against similar Soviet units. Clearly, the StuG and Pz IV were far more often directly destroyed by hits from enemy units. On the other hand, there seems to have been significantly fewer cases of mechanical breakdown among StuG and Pz IV. Ten such cases are explicitly mentioned, but in many cases the war diary just says that a tank was out of action, without giving a cause. Most likely, in those cases the cause was enemy action.

Clearly the proportions between destroyed by enemy fire, damaged by enemy fire and lost due to other causes differ considerably between the III./Pz.Rgt 36 and I./Pz.Rgt. 26.

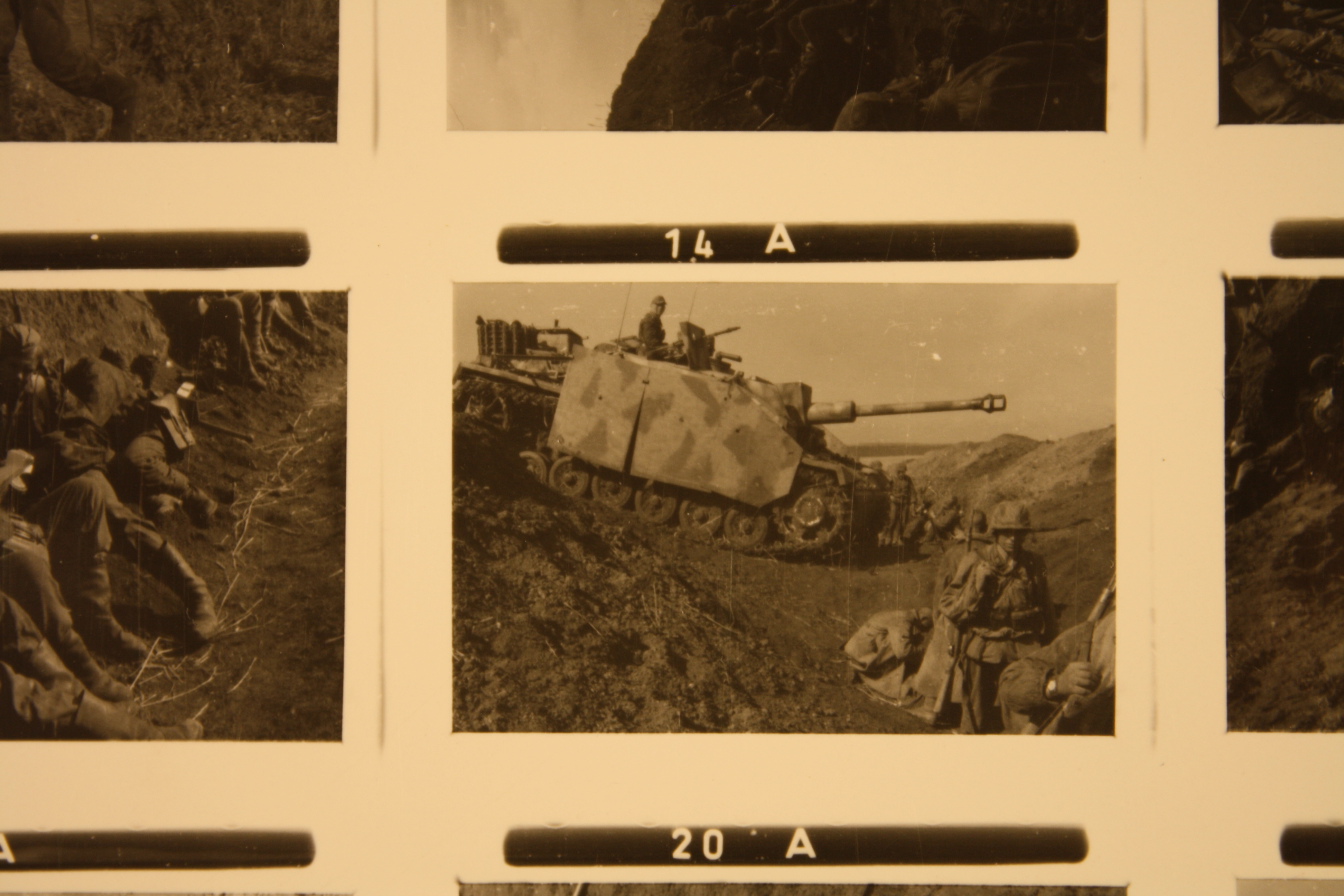

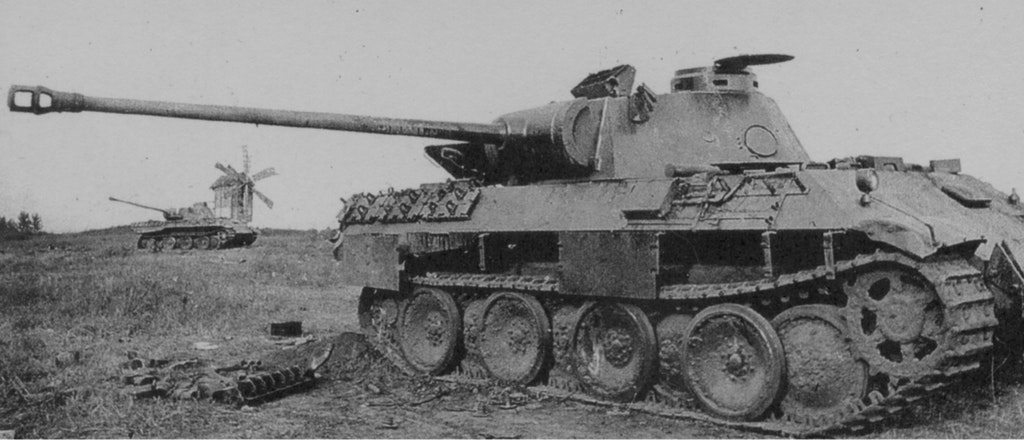

This Picture is TAKEN FROM The SS Panzer corps in July 1943.

This blog

This blog