While perusing Charles Shrader’s fascinating history of the U.S. Army’s experience with operations research (OR), I came across several references to the part played by historians and historical analysis in early era of that effort.

While perusing Charles Shrader’s fascinating history of the U.S. Army’s experience with operations research (OR), I came across several references to the part played by historians and historical analysis in early era of that effort.

The ground forces were the last branch of the Army to incorporate OR into their efforts during World War II, lagging behind the Army Air Forces, the technical services, and the Navy. Where the Army was a step ahead, however, was in creating a robust wartime historical field history documentation program. (After the war, this enabled the publication of the U.S. Army in World War II series, known as the “Green Books,” which set a new standard for government sponsored military histories.)

As Shrader related, the first OR personnel the Army deployed forward in 1944-45 often crossed paths with War Department General Staff Historical Branch field historian detachments. They both engaged in similar activities: collecting data on real-world combat operations, which was then analyzed and used for studies and reports written for the use of the commands to which they were assigned. The only significant difference was in their respective methodologies, with the historians using historical methods and the OR analysts using mathematical and scientific tools.

History and OR after World War II

The usefulness of historical approaches to collecting operational data did not go unnoticed by the OR practitioners, according to Shrader. When the Army established the Operations Research Office (ORO) in 1948, it hired a contingent of historians specifically for the purpose of facilitating research and analysis using WWII Army records, “the most likely source for data on operational matters.”

When the Korean War broke out in 1950, ORO sent eight multi-disciplinary teams, including the historians, to collect operational data and provide analytical support for U.S. By 1953, half of ORO’s personnel had spent time in combat zones. Throughout the 1950s, about 40-43% of ORO’s staff was comprised of specialists in the social sciences, history, business, literature, and law. Shrader quoted one leading ORO analyst as noting that, “there is reason to believe that the lawyer, social scientist or historian is better equipped professionally to evaluate evidence which is derived from the mind and experience of the human species.”

Among the notable historians who worked at or with ORO was Dr. Hugh M. Cole, an Army officer who had served as a staff historian for General George Patton during World War II. Cole rose to become a senior manager at ORO and later served as vice-president and president of ORO’s successor, the Research Analysis Corporation (RAC). Cole brought in WWII colleague Forrest C. Pogue (best known as the biographer of General George C. Marshall) and Charles B. MacDonald. ORO also employed another WWII field historian, the controversial S. L. A. Marshall, as a consultant during the Korean War. Dorothy Kneeland Clark did pioneering historical analysis on combat phenomena while at ORO.

The Demise of ORO…and Historical Combat Analysis?

By the late 1950s, considerable institutional friction had developed between ORO, the Johns Hopkins University (JHU)—ORO’s institutional owner—and the Army. According to Shrader,

Continued distrust of operations analysts by Army personnel, questions about the timeliness and focus of ORO studies, the ever-expanding scope of ORO interests, and, above all, [ORO director] Ellis Johnson’s irascible personality caused tensions that led in August 1961 to the cancellation of the Army’s contract with JHU and the replacement of ORO with a new, independent research organization, the Research Analysis Corporation [RAC].

RAC inherited ORO’s research agenda and most of its personnel, but changing events and circumstances led Army OR to shift its priorities away from field collection and empirical research on operational combat data in favor of the use of modeling and wargaming in its analyses. As Chris Lawrence described in his history of federally-funded Defense Department “think tanks,” the rise and fall of scientific management in DOD, the Vietnam War, social and congressional criticism, and an unhappiness by the military services with the analysis led to retrenchment in military OR by the end of the 60s. The Army sold RAC and created its own in-house Concepts Analysis Agency (CAA; now known as the Center for Army Analysis).

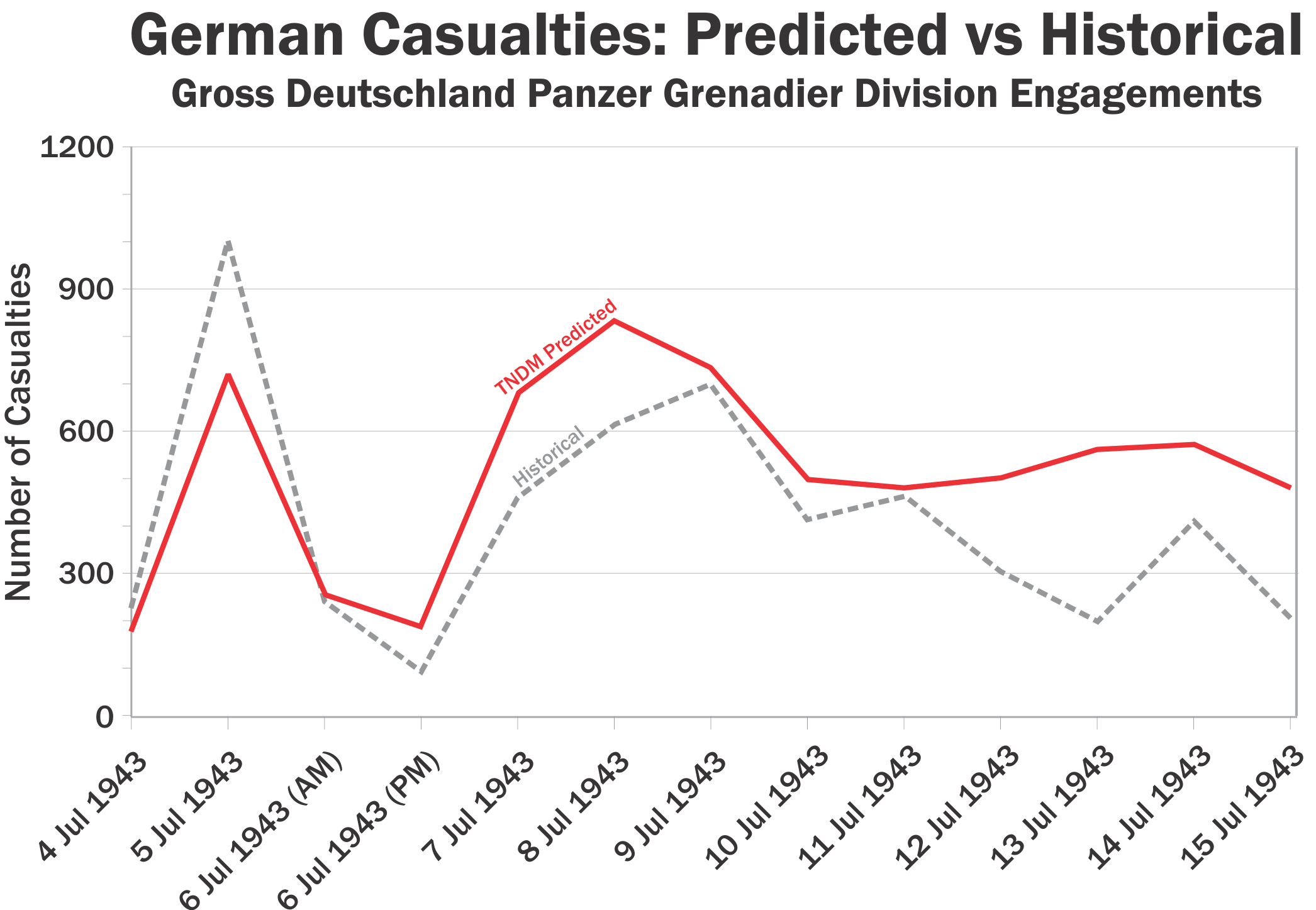

By the early 1970s, analysts, such as RAND’s Martin Shubik and Gary Brewer, and John Stockfisch, began to note that the relationships and processes being modeled in the Army’s combat simulations were not based on real-world data and that empirical research on combat phenomena by the Army OR community had languished. In 1991, Paul Davis and Donald Blumenthal gave this problem a name: the “Base of Sand.”

While perusing Charles Shrader’s fascinating

While perusing Charles Shrader’s fascinating