[This piece was originally posted on 13 July 2016.]

[This piece was originally posted on 13 July 2016.]

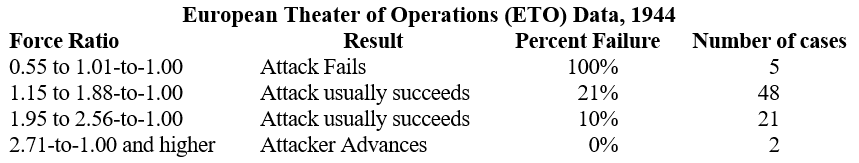

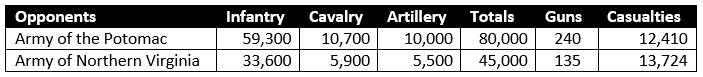

Trevor Dupuy’s article cited in my previous post, “Combat Data and the 3:1 Rule,” was the final salvo in a roaring, multi-year debate between two highly regarded members of the U.S. strategic and security studies academic communities, political scientist John Mearsheimer and military analyst/polymath Joshua Epstein. Carried out primarily in the pages of the academic journal International Security, Epstein and Mearsheimer argued the validity of the 3-1 rule and other analytical models with respect the NATO/Warsaw Pact military balance in Europe in the 1980s. Epstein cited Dupuy’s empirical research in support of his criticism of Mearsheimer’s reliance on the 3-1 rule. In turn, Mearsheimer questioned Dupuy’s data and conclusions to refute Epstein. Dupuy’s article defended his research and pointed out the errors in Mearsheimer’s assertions. With the publication of Dupuy’s rebuttal, the International Security editors called a time out on the debate thread.

The Epstein/Mearsheimer debate was itself part of a larger political debate over U.S. policy toward the Soviet Union during the administration of Ronald Reagan. This interdisciplinary argument, which has since become legendary in security and strategic studies circles, drew in some of the biggest names in these fields, including Eliot Cohen, Barry Posen, the late Samuel Huntington, and Stephen Biddle. As Jeffery Friedman observed,

These debates played a prominent role in the “renaissance of security studies” because they brought together scholars with different theoretical, methodological, and professional backgrounds to push forward a cohesive line of research that had clear implications for the conduct of contemporary defense policy. Just as importantly, the debate forced scholars to engage broader, fundamental issues. Is “military power” something that can be studied using static measures like force ratios, or does it require a more dynamic analysis? How should analysts evaluate the role of doctrine, or politics, or military strategy in determining the appropriate “balance”? What role should formal modeling play in formulating defense policy? What is the place for empirical analysis, and what are the strengths and limitations of existing data?[1]

It is well worth the time to revisit the contributions to the 1980s debate. I have included a bibliography below that is not exhaustive, but is a place to start. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War diminished the intensity of the debates, which simmered through the 1990s and then were obscured during the counterterrorism/ counterinsurgency conflicts of the post-9/11 era. It is possible that the challenges posed by China and Russia amidst the ongoing “hybrid” conflict in Syria and Iraq may revive interest in interrogating the bases of military analyses in the U.S and the West. It is a discussion that is long overdue and potentially quite illuminating.

NOTES

[1] Jeffery A. Friedman, “Manpower and Counterinsurgency: Empirical Foundations for Theory and Doctrine,” Security Studies 20 (2011)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

(Note: Some of these are behind paywalls, but some are available in PDF format. Mearsheimer has made many of his publications freely available here.)

John J. Mearsheimer, “Why the Soviets Can’t Win Quickly in Central Europe,” International Security, Vol. 7, No. 1 (Summer 1982)

Samuel P. Huntington, “Conventional Deterrence and Conventional Retaliation in Europe,” International Security 8, no. 3 (Winter 1983/84)

Joshua Epstein, Strategy and Force Planning (Washington, DC: Brookings, 1987)

Joshua M. Epstein, “Dynamic Analysis and the Conventional Balance in Europe,” International Security 12, no. 4 (Spring 1988)

John J. Mearsheimer, “Numbers, Strategy, and the European Balance,” International Security 12, no. 4 (Spring 1988)

Stephen Biddle, “The European Conventional Balance,” Survival 30, no. 2 (March/April 1988)

Eliot A. Cohen, “Toward Better Net Assessment: Rethinking the European Conventional Balance,” International Security Vol. 13, No. 1 (Summer 1988)

Joshua M. Epstein, “The 3:1 Rule, the Adaptive Dynamic Model, and the Future of Security Studies,” International Security 13, no. 4 (Spring 1989)

John J. Mearsheimer, “Assessing the Conventional Balance,” International Security 13, no. 4 (Spring 1989)

John J. Mearsheimer, Barry R. Posen, Eliot A. Cohen, “Correspondence: Reassessing Net Assessment,” International Security 13, No. 4 (Spring 1989)

Trevor N. Dupuy, “Combat Data and the 3:1 Rule,” International Security 14, no. 1 (Summer 1989)

Stephen Biddle et al., Defense at Low Force Levels (Alexandria, VA: Institute for Defense Analyses, 1991)