One of Trevor Dupuy’s more important and controversial contributions to a theory of combat was the assertion that outcomes were dictated in part by behavioral factors, i.e. the human element. Among the influential human factors he identified were leadership, training, experience, and manpower quality. He also recognized the importance of morale.

Morale is an ephemeral quality of military forces and is certainly intangible. Yet even though it may not be easily defined and can probably never be quantified, troop morale is very real and can be very important as a contributor to victory or defeat. The significance of morale is probably inversely proportional to the quality of troops. A well-trained, well-led, cohesive force of veterans will fight well and effectively even if morale is low… Yet for ordinary armies, poor morale can contribute to defeat.[1]

Dr. Jonathan Fennell of the Defence Studies Department at King’s College London recently set out to determine if there were ways of measuring morale by looking at the combat experiences of the British Army in World War II. Fennell proposed

that the concept of morale has no place in a critical analysis of the past unless it is clearly differentiated from definitions associated solely or primarily with mood or cohesion and the group. Instead, for morale to have explanatory value, particularly in a combat environment, a functional conceptualisation is proposed, which, while not excluding the role of mood or group cohesion, focuses its meaning and relevance on motivation and the willingness to act in a manner required by an authority or institution.

Fennell constructed a multi-dimensional model of morale

By drawing on studies made across the social sciences and on primary archival evidence from the British and Commonwealth Army’s experiences in North Africa in the Second World War… It suggests that morale can best be understood as emerging from the subtle interdependencies and interrelationships of the many factors known to affect military means.

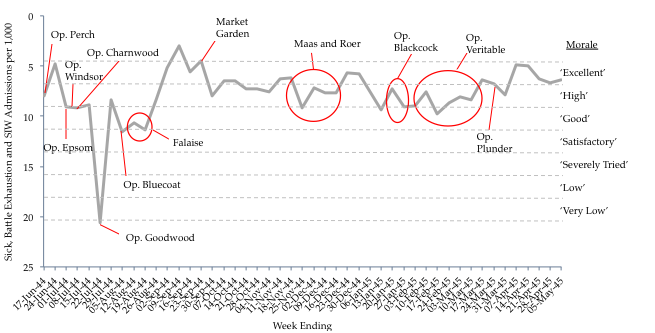

Fennell tested his methodology by developing a weekly morale score using bi-weekly censorship summaries of letters and correspondence from members of the British Second Army in the Northwest Europe Campaign in 1944-45.

These summaries proved a useful source to describe and ‘quantify’ levels of morale (through the use of a numerical morale scale). Where morale was described as ‘excellent’, it was awarded a score of 3. ‘High’ morale was given a score of 2 and ‘good’ morale was scored 1. ‘Satisfactory’ morale was given a score of 0 (neither positive or negative). Morale described as ‘severely tried’ was scored -1, while ‘low’ and ‘very low’ morale were scored -2 and -3 respectively.

He then correlated these scores with weekly statistics compiled by the British Second Army and 21st Army Group on rates of sickness, battle exhaustion, desertion, absence without leave (AWOL) and self-inflicted wounds (SIW).

The results of the correlation analysis showed that the tabulated rates (the combined rate of sickness, battle exhaustion, desertion, AWOL and SIW) had an extremely strong negative correlation with morale (-0.949, P<0.001), i.e. when morale was high, sickness rates etc. were low, and when morale was low, sickness rates etc. were high. This is a remarkably strong relationship and shows that these factors when taken together can be used as a quantitative method to assess levels of morale, at the very least for the Army and campaign under discussion.

The results are shown on the graph above. According to Fennell,

This analysis of morale supports the conclusions of much of the recent historiography on the British Army in Northwest Europe; morale was a necessary component of combat effectiveness (morale in Second Army was broadly speaking high throughout the victorious campaign); however, morale was not a sufficient explanation for Second Army’s successes and failures on the battlefield. For example, morale would appear to have been at its highest before and during Operation ‘Market Garden’. But ‘Market Garden’ was a failure. It is likely, as John Buckley has argued, that ‘Market Garden’ was a conceptual failure rather than a morale one. Morale would also appear to have been mostly high during operations in the Low Countries and Germany, but these operations were beset with setbacks and delays.

Fennell further explored the relationship between morale and combat performance, and combat performance and strategy, in his contribution to Anthony King, ed., Frontline: Combat and Cohesion in the Twenty-First Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015). An earlier version of his chapter can be found here.

NOTES

[1] Trevor N. Dupuy, Understanding Defeat: How To Recover From Loss In Battle To Gain Victory In War (New York: Paragon House, 1990), p. 67