One of the primary scenarios the Third Offset Strategy is intended to address is a potential military conflict between the United States and the People’s Republic of China over the sovereignty of the Republic of China (Taiwan) and territorial control of the South and East China Seas. As surveyed by James Holmes in a wonderful Mahanian geopolitical analysis, the South China Sea is a semi-enclosed sea at the intersection between East Asia and the Indian Ocean region, bounded by strategic gaps and choke points between island chains, atolls, and reefs, and riven by competing territorial claims among rising and established regional powers.

One of the primary scenarios the Third Offset Strategy is intended to address is a potential military conflict between the United States and the People’s Republic of China over the sovereignty of the Republic of China (Taiwan) and territorial control of the South and East China Seas. As surveyed by James Holmes in a wonderful Mahanian geopolitical analysis, the South China Sea is a semi-enclosed sea at the intersection between East Asia and the Indian Ocean region, bounded by strategic gaps and choke points between island chains, atolls, and reefs, and riven by competing territorial claims among rising and established regional powers.

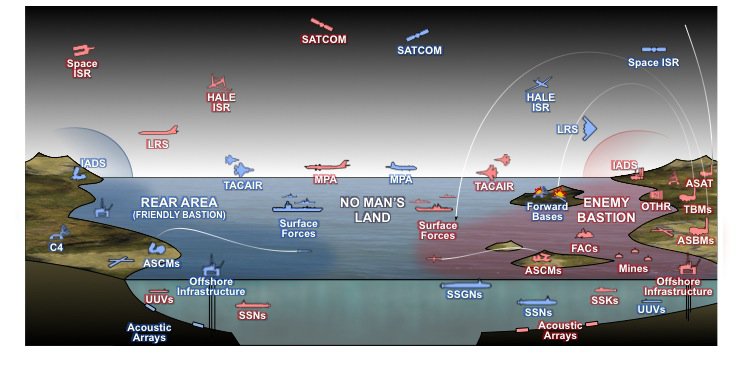

China’s current policy appears to be to develop the ability to assert military control over the Western Pacific and deny U.S. armed forces access to the area in case of overt conflict. The strategic dimension is framed by China’s pursuit of anti-access/area denial (A2/D2) capabilities enabled by development of sophisticated long-range strike, sensor, guidance, and other military technologies, and the use of asymmetrical warfare operational concepts such as psychological and information operations, and “lawfare” (the so-called “three warfares.”) China is also advancing its interests in decidedly low-tech ways as well, such as creating artificial islands on disputed reefs through dredging.

The current U.S. approach to thwarting China’s A2/D2 strategy is the Joint Concept for Access and Maneuver in the Global Commons (JAM-GC, aka “Jam Gee Cee”), or the concept formerly known as AirSea Battle. As described by Stephen Biddle and Ivan Oelrich, the current iteration of JAM-GC

…is designed to preserve U.S. access to the Western Pacific by combining passive defenses against Chinese missile attack with an emphasis on offensive action to destroy or disable the forces that China would use to establish A2/AD. This offensive action would use “cross-domain synergy” among U.S. space, cyber, air, and maritime forces (hence the moniker “AirSea”) to blind or suppress Chinese sensors. The heart of the concept, however, lies in physically destroying the Chinese weapons and infrastructure that underpin A2/AD.

The brute, counterforce character of JAM-GC provides the logic behind proposals for new long-range precision strike weapons such as the Air Force’s stealthy Long Range Strike-Bomber (LRS-B) program, recently designated the B-21 Raider.

The JAM-GC concept has not yet been officially set and continues to evolve. Both the A2/D2 construct and the premises behind JAM-GC are being challenged. As Biddle and Oelrich conclude in their detailed analysis of the strategic and military trends in the region, it is not at all clear that China’s A2/D2 approach will actually achieve its goal.

[W]e find that by 2040 China will not achieve military hegemony over the Western Pacific or anything close to it—even without ASB. A2/AD is giving air and maritime defenders increasing advantages, but those advantages are strongest over controlled landmasses and weaken over distance. As both sides deploy A2/AD, these capabilities will increasingly replace today’s U.S. command of the global commons not with Chinese hegemony but with a more differentiated pattern of control, with a U.S. sphere of influence around allied landmasses, a Chinese sphere of influence over the Chinese mainland, and contested battlespace covering much of the South and East China Seas, wherein neither power enjoys wartime freedom of surface or air movement.

They also raise deeper concerns about JAM-GC’s emphasis on an aggressive counterforce posture. In an era of constrained defense spending, developing and acquiring the military capability to execute it could be costly. Also, long-range air and missile strikes against the Chinese mainland runs the distinct risk of escalating a regional conflict into a general war between nuclear armed opponents.

A recent RAND analysis echoed these conclusions. The adoption of counterforce strategies by both the U.S. and China would result in heavy military losses by both sides that would make it difficult to constrain a longer, broader conflict. Although the RAND analysts foresee the U.S. prevailing in such a conflict, it would not be quick and the ramifications to both sides would be severe.

Dissatisfaction with these options and potential outcomes is partly what motivated the development of the Third Offset Strategy in the first place. It is not clear whether leveraging technological innovation can provide new operational capabilities that will enable successful solutions to these strategic dilemmas. What does seem apparent is that fresh thinking is needed.

![The Remote Controlled Abrams Tank [Hammacher Schlemmer]](https://dupuyinstitute.dreamhosters.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/remote-control-m1a2-abrams-tank-xl.jpg)