Preamble & Warning (P&W): Please forgive me, this is an acronym heavy post.

In May 2013, the U.S. Navy (USN) reached milestones by having a “drone,” or unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) land and take-off from an aircraft carrier. This was a significant achievement in aviation, and heralded an era of combat UAVs (UCAV) being integrated into carrier air wings (CVW). This vehicle, the X-47B, was built by Northrup Grumman, under the concept of a carrier-based stealthy strike vehicle.

Ultimately, after almost three years, their decision was announced:

On 1 February 2016, after many delays over whether the [Unmanned Carrier-Launched Airborne Surveillance and Strike] UCLASS would specialize in strike or intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) roles, it was reported that a significant portion of the UCLASS effort would be directed to produce a Super Hornet-sized carrier-based aerial refueling tanker as the Carrier-Based Aerial-Refueling System (CBARS), with ‘a little ISR’ and some capabilities for communications relay, and strike capabilities put off to a future version of the aircraft. In July 2016, it was officially named ‘MQ-25A Stingray’.

The USN, who had just proven that they can add a stealthy UCAV to carrier flight deck operations, decided to put this new capability on the shelf, and instead refocus the efforts of the aerospace defense industry on a brand new requirement, namely …

For mission tanking, the threshold requirement is offloading 14,000 lb. of fuel to aviation assets at 500 nm from the ship, thereby greatly extending the range of the carrier air wing, including the Lockheed Martin F-35C and Boeing F/A-18 Super Hornet. The UAV must also be able to integrate with the Nimitz-class carriers, being able to safely launch and recover and not take up more space than is allocated for storage, maintenance and repairs.

Why did they do this?

The Pentagon apparently made this program change in order to address the Navy’s expected fighter shortfall by directing funds to buy additional F/A-18E/F Super Hornets and accelerate purchases and development of the F-35C. Having the CBARS as the first carrier-based UAV provides a less complex bridge to the future F/A-XX, should it be an autonomous strike platform. It also addresses the carriers’ need for an organic refueling aircraft, proposed as a mission for the UCLASS since 2014, freeing up the 20–30 percent of Super Hornets performing the mission in a more capable and cost effective manner than modifying the F-35, V-22 Osprey, and E-2D Hawkeye, or bringing the retired S-3 Viking back into service.

Notice within this quote the supposition that the F/A-XX would be an autonomous strike platform. This program was originally a USN-specific program to build a next-generation platform to perform both strike and air superiority missions, much like the F/A-18 aircraft are “swing role.” The US Air Force (USAF) had a separate program for a next generation air superiority aircraft called the F-X. These programs were combined by the Department of Defense (DoD) into the Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) program. We can tell from the name of this program that it is clearly focused on the air superiority mission, as compared to the balance of strike and superiority, implicit in the USN program.

Senator John McCain, chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee (SASC), wrote a letter to then Secretary of Defense Ash Carter, on 2015-03-24, stating, “I strongly believe that the Navy’s first operational unmanned combat aircraft must be capable of performing a broad range of missions in contested environments as part of the carrier air wing, including precision strike as well as [ISR].” This is effectively an endorsement of the X-47B, and quite unlike the MQ-25.

I’m in agreement with Senator McCain on this. I think that a great deal of experience could have been gained by continuing the development and test of the X-47B, and possibly deploying the vehicle to the fleet.

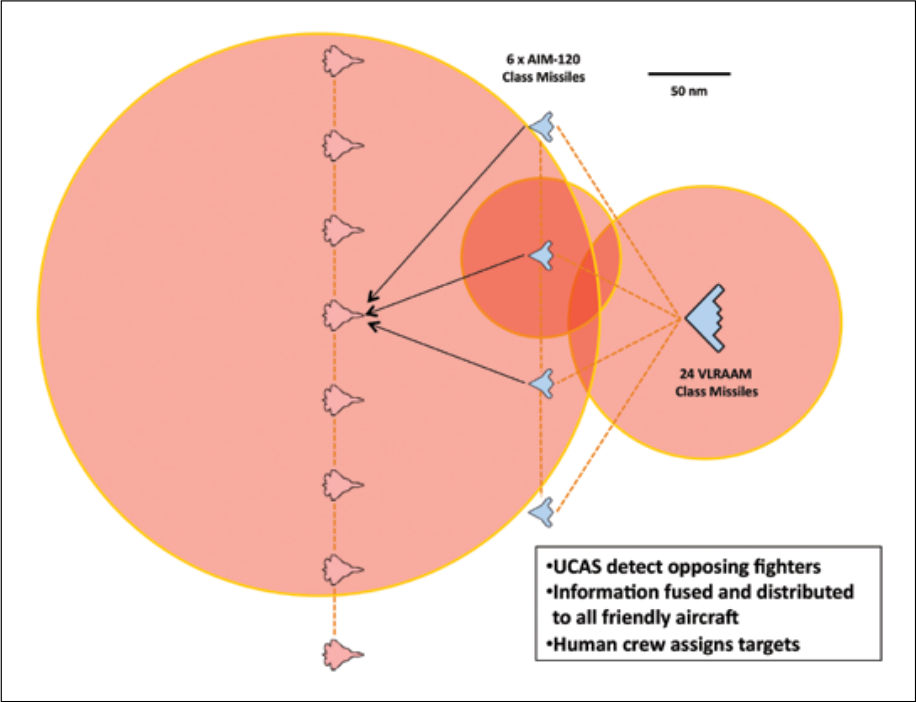

The Navy hinted at the possibility of using the UCLASS in air-to-air engagements as a ‘flying missile magazine’ to supplement the F/A-18 Super Hornet and F-35C Lightning II as a type of ‘robotic wingman.’ Its weapons bay could be filled with AIM-120 AMRAAMs and be remotely operated by an E-2D Hawkeye or F-35C flight leader, using their own sensors and human judgment to detect, track, and direct the UAV to engage an enemy aircraft. The Navy’s Naval Integrated Fire Control-Counter Air (NIFC-CA) concept gives a common picture of the battle space to multiple air platforms through data-links, where any aircraft could fire on a target in their range that is being tracked by any sensor, so the forward deployed UCLASS would have its missiles targeted by another controller. With manned-unmanned teaming for air combat, a dedicated unmanned supersonic fighter may not be developed, as the greater cost of high-thrust propulsion and an airframe of similar size to a manned fighter would deliver a platform with comparable operating costs and still without an ability to engage on its own.

Indeed, the German Luftwaffe has completed an air combat concept study, stating that the fighter of the 2040’s will be a “stealthy drone herder”:

Interestingly the twin-engine, twin-tail stealth design would be a twin-seat design, according to Alberto Gutierrez, Head of Eurofighter Programme, Airbus DS. The second crewmember may be especially important for the FCAS concept of operations, which would see it operate in a wider battle network, potentially as a command and control asset or UCAV/UAV mission commander.

Instead, the USN has decided to banish the drones into the tanker and light ISR roles, to focus on having more Super Hornets available, and move towards integrating the F-35C into the CVW. I believe that this is a missed opportunity to move ahead to get direct front line experience in operating UCAVs as part of combat carrier operations.

We are trying something new today, well, new for TDI anyway. This edition of TDI Friday Read will offer a selection of links to items we think may be of interest to our readers. We found them interesting but have not had the opportunity to offer observations or commentary about them. Hopefully you may find them useful or interesting as well.

We are trying something new today, well, new for TDI anyway. This edition of TDI Friday Read will offer a selection of links to items we think may be of interest to our readers. We found them interesting but have not had the opportunity to offer observations or commentary about them. Hopefully you may find them useful or interesting as well.