Trevor Dupuy was skeptical about the role of technology in determining outcomes in warfare. While he did believe technological innovation was crucial, he did not think that technology itself has decided success or failure on the battlefield. As he wrote posthumously in 1997,

I am a humanist, who is also convinced that technology is as important today in war as it ever was (and it has always been important), and that any national or military leader who neglects military technology does so to his peril and that of his country. But, paradoxically, perhaps to an extent even greater than ever before, the quality of military men is what wins wars and preserves nations. (emphasis added)

His conclusion was largely based upon his quantitative approach to studying military history, particularly the way humans have historically responded to the relentless trend of increasingly lethal military technology.

The Historical Relationship Between Weapon Lethality and Battle Casualty Rates

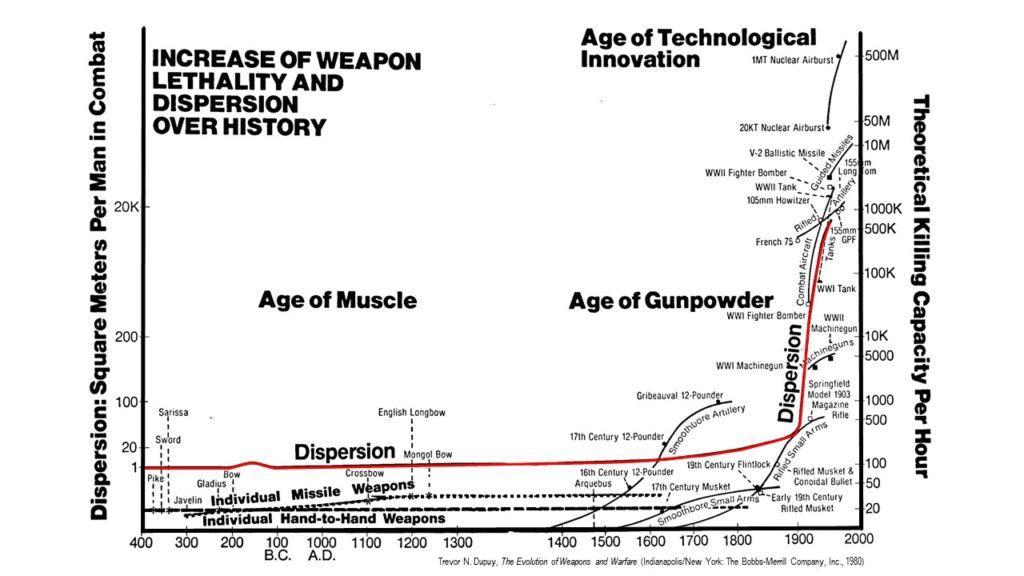

Based on a 1964 study for the U.S. Army, Dupuy identified a long-term historical relationship between increasing weapon lethality and decreasing average daily casualty rates in battle. (He summarized these findings in his book, The Evolution of Weapons and Warfare (1980). The quotes below are taken from it.)

Since antiquity, military technological development has produced weapons of ever increasing lethality. The rate of increase in lethality has grown particularly dramatically since the mid-19th century.

However, in contrast, the average daily casualty rate in combat has been in decline since 1600. With notable exceptions during the 19th century, casualty rates have continued to fall through the late 20th century. If technological innovation has produced vastly more lethal weapons, why have there been fewer average daily casualties in battle?

However, in contrast, the average daily casualty rate in combat has been in decline since 1600. With notable exceptions during the 19th century, casualty rates have continued to fall through the late 20th century. If technological innovation has produced vastly more lethal weapons, why have there been fewer average daily casualties in battle?

The primary cause, Dupuy concluded, was that humans have adapted to increasing weapon lethality by changing the way they fight. He identified three key tactical trends in the modern era that have influenced the relationship between lethality and casualties:

The primary cause, Dupuy concluded, was that humans have adapted to increasing weapon lethality by changing the way they fight. He identified three key tactical trends in the modern era that have influenced the relationship between lethality and casualties:

- Having reached their physical and psychological limits of endurance in battle, combatants have dispersed physically in frontage and depth on the battlefield, seeking advantage from cover and concealment;

- the granting of greater freedom to maneuver through decentralized decision-making and enhanced mobility; and

- improved use of combined arms and interservice coordination.

Technological Innovation and Organizational Assimilation

Dupuy noted that the historical correlation between weapons development and their use in combat has not been linear because the pace of integration has been largely determined by military leaders, not the rate of technological innovation. “The process of doctrinal assimilation of new weapons into compatible tactical and organizational systems has proved to be much more significant than invention of a weapon or adoption of a prototype, regardless of the dimensions of the advance in lethality.” [p. 337]

As a result, the history of warfare has been exemplified more often by a discontinuity between weapons and tactical systems than effective continuity.

During most of military history there have been marked and observable imbalances between military efforts and military results, an imbalance particularly manifested by inconclusive battles and high combat casualties. More often than not this imbalance seems to be the result of incompatibility, or incongruence, between the weapons of warfare available and the means and/or tactics employing the weapons. [p. 341]

In short, military organizations typically have not been fully effective at exploiting new weapons technology to advantage on the battlefield. Truly decisive alignment between weapons and systems for their employment has been exceptionally rare. Dupuy asserted that

There have been six important tactical systems in military history in which weapons and tactics were in obvious congruence, and which were able to achieve decisive results at small casualty costs while inflicting disproportionate numbers of casualties. These systems were:

- the Macedonian system of Alexander the Great, ca. 340 B.C.

- the Roman system of Scipio and Flaminius, ca. 200 B.C.

- the Mongol system of Ghengis Khan, ca. A.D. 1200

- the English system of Edward I, Edward III, and Henry V, ca. A.D. 1350

- the French system of Napoleon, ca. A.D. 1800

- the German blitzkrieg system, ca. A.D. 1940 [p. 341]

With one caveat, Dupuy could not identify any single weapon that had decisively changed warfare in of itself without a corresponding human adaptation in its use on the battlefield.

Save for the recent significant exception of strategic nuclear weapons, there have been no historical instances in which new and lethal weapons have, of themselves, altered the conduct of war or the balance of power until they have been incorporated into a new tactical system exploiting their lethality and permitting their coordination with other weapons; the full significance of this one exception is not yet clear, since the changes it has caused in warfare and the influence it has exerted on international relations have yet to be tested in war.

Until the present time, the application of sound, imaginative thinking to the problem of warfare (on either an individual or an institutional basis) has been more significant than any new weapon; such thinking is necessary to real assimilation of weaponry; it can also alter the course of human affairs without new weapons. [p. 340]

Technological Superiority and Offset Strategies

Will new technologies like robotics and artificial intelligence provide the basis for a seventh tactical system where weapons and their use align with decisive battlefield results? Maybe. If Dupuy’s analysis is accurate, however, it is more likely that future increases in weapon lethality will continue to be counterbalanced by human ingenuity in how those weapons are used, yielding indeterminate—perhaps costly and indecisive—battlefield outcomes.

Genuinely effective congruence between weapons and force employment continues to be difficult to achieve. Dupuy believed the preconditions necessary for successful technological assimilation since the mid-19th century have been a combination of conducive military leadership; effective coordination of national economic, technological-scientific, and military resources; and the opportunity to evaluate and analyze battlefield experience.

Can the U.S. meet these preconditions? That certainly seemed to be the goal of the so-called Third Offset Strategy, articulated in 2014 by the Obama administration. It called for maintaining “U.S. military superiority over capable adversaries through the development of novel capabilities and concepts.” Although the Trump administration has stopped using the term, it has made “maximizing lethality” the cornerstone of the 2018 National Defense Strategy, with increased funding for the Defense Department’s modernization priorities in FY2019 (though perhaps not in FY2020).

Dupuy’s original work on weapon lethality in the 1960s coincided with development in the U.S. of what advocates of a “revolution in military affairs” (RMA) have termed the “First Offset Strategy,” which involved the potential use of nuclear weapons to balance Soviet superiority in manpower and material. RMA proponents pointed to the lopsided victory of the U.S. and its allies over Iraq in the 1991 Gulf War as proof of the success of a “Second Offset Strategy,” which exploited U.S. precision-guided munitions, stealth, and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance systems developed to counter the Soviet Army in Germany in the 1980s. Dupuy was one of the few to attribute the decisiveness of the Gulf War both to airpower and to the superior effectiveness of U.S. combat forces.

Trevor Dupuy certainly was not an anti-technology Luddite. He recognized the importance of military technological advances and the need to invest in them. But he believed that the human element has always been more important on the battlefield. Most wars in history have been fought without a clear-cut technological advantage for one side; some have been bloody and pointless, while others have been decisive for reasons other than technology. While the future is certainly unknown and past performance is not a guarantor of future results, it would be a gamble to rely on technological superiority alone to provide the margin of success in future warfare.

Between 2001 and 2004, TDI undertook a series of studies on the effects of urban combat in cities for the U.S. Army Center for Army Analysis (CAA). These studies examined a total of 304 cases of urban combat at the divisional and battalion level that occurred between 1942 and 2003, as well as 319 cases of concurrent non-urban combat for comparison.

Between 2001 and 2004, TDI undertook a series of studies on the effects of urban combat in cities for the U.S. Army Center for Army Analysis (CAA). These studies examined a total of 304 cases of urban combat at the divisional and battalion level that occurred between 1942 and 2003, as well as 319 cases of concurrent non-urban combat for comparison.