[This article was originally posted on 11 October 2016]

[This article was originally posted on 11 October 2016]

In 2004, military analyst and academic Stephen Biddle published Military Power: Explaining Victory and Defeat in Modern Battle, a book that addressed the fundamental question of what causes victory and defeat in battle. Biddle took to task the study of the conduct of war, which he asserted was based on “a weak foundation” of empirical knowledge. He surveyed the existing literature on the topic and determined that the plethora of theories of military success or failure fell into one of three analytical categories: numerical preponderance, technological superiority, or force employment.

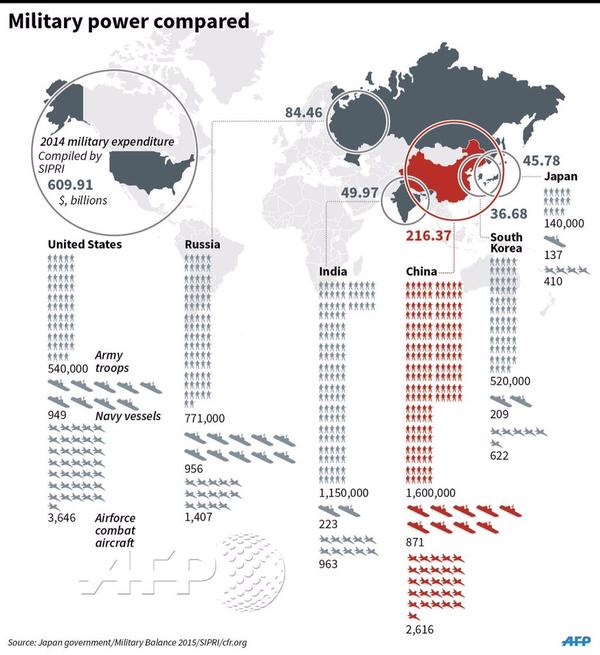

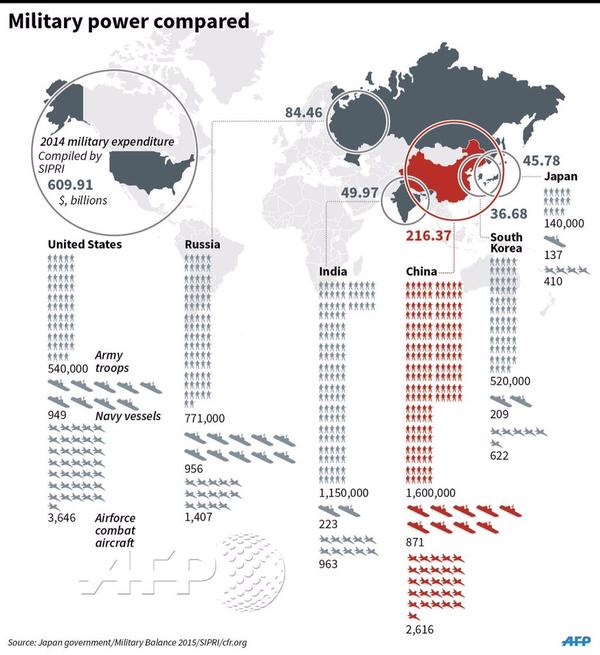

Numerical preponderance theories explain victory or defeat in terms of material advantage, with the winners possessing greater numbers of troops, populations, economic production, or financial expenditures. Many of these involve gross comparisons of numbers, but some of the more sophisticated analyses involve calculations of force density, force-to-space ratios, or measurements of quality-adjusted “combat power.” Notions of threshold “rules of thumb,” such as the 3-1 rule, arise from this. These sorts of measurements form the basis for many theories of power in the study of international relations.

The next most influential means of assessment, according to Biddle, involve views on the primacy of technology. One school, systemic technology theory, looks at how technological advances shift balances within the international system. The best example of this is how the introduction of machine guns in the late 19th century shifted the advantage in combat to the defender, and the development of the tank in the early 20th century shifted it back to the attacker. Such measures are influential in international relations and political science scholarship.

The other school of technological determinacy is dyadic technology theory, which looks at relative advantages between states regardless of posture. This usually involves detailed comparisons of specific weapons systems, tanks, aircraft, infantry weapons, ships, missiles, etc., with the edge going to the more sophisticated and capable technology. The use of Lanchester theory in operations research and combat modeling is rooted in this thinking.

Biddle identified the third category of assessment as subjective assessments of force employment based on non-material factors including tactics, doctrine, skill, experience, morale or leadership. Analyses on these lines are the stock-in-trade of military staff work, military historians, and strategic studies scholars. However, international relations theorists largely ignore force employment and operations research combat modelers tend to treat it as a constant or omit it because they believe its effects cannot be measured.

The common weakness of all of these approaches, Biddle argued, is that “there are differing views, each intuitively plausible but none of which can be considered empirically proven.” For example, no one has yet been able to find empirical support substantiating the validity of the 3-1 rule or Lanchester theory. Biddle notes that the track record for predictions based on force employment analyses has also been “poor.” (To be fair, the problem of testing theory to see if applies to the real world is not limited to assessments of military power, it afflicts security and strategic studies generally.)

So, is Biddle correct? Are there only three ways to assess military outcomes? Are they valid? Can we do better?

Armies have historically responded to the increasing lethality of weapons by dispersing mass in frontage and depth on the battlefield. Will combat see a new period of adjustment over the next 50 years like the previous half-century, where dispersion continues to shift in direct proportion to increased weapon range and precision, or will there be a significant change in the character of warfare?

Armies have historically responded to the increasing lethality of weapons by dispersing mass in frontage and depth on the battlefield. Will combat see a new period of adjustment over the next 50 years like the previous half-century, where dispersion continues to shift in direct proportion to increased weapon range and precision, or will there be a significant change in the character of warfare?

[This article was originally posted on 11 October 2016]

[This article was originally posted on 11 October 2016]