A number of forecasts of potential U.S. casualties in a war to evict Iraqi forces from Kuwait appeared in the media in the autumn of 1990. The question of the human costs became a political issue for the administration of George H. W. Bush and influenced strategic and military decision-making.

A number of forecasts of potential U.S. casualties in a war to evict Iraqi forces from Kuwait appeared in the media in the autumn of 1990. The question of the human costs became a political issue for the administration of George H. W. Bush and influenced strategic and military decision-making.

Almost immediately following President Bush’s decision to commit U.S. forces to the Middle East in August 1990, speculation appeared in the media about what a war between Iraq and a U.S.-led international coalition might entail. In early September, U.S. News & World Report reported “that the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff and the National Security Council estimated that the United States would lose between 20,000 and 30,000 dead and wounded soldiers in a Gulf war.” The Bush administration declined official comment on these figures at the time, but the media indicated that they were derived from Defense Department computer models used to wargame possible conflict scenarios.[1] The numbers shocked the American public and became unofficial benchmarks in subsequent public discussion and debate.

A Defense Department wargame exploring U.S. options in Iraq had taken place on 25 August, the results of which allegedly led to “major changes” in military planning.[2] Although linking the wargame and the reported casualty estimate is circumstantial, the cited figures were very much in line with other contemporary U.S. military casualty estimates. A U.S. Army Personnel Command [PERSCOM] document that informed U.S. Central Command [USCENTCOM] troop replacement planning, likely based on pre-crisis plans for the defense of Saudi Arabia against possible Iraqi invasion, anticipated “about 40,000” total losses.[3]

These early estimates were very likely to have been based on a concept plan involving a frontal attack on Iraqi forces in Kuwait using a single U.S. Army corps and a U.S. Marine Expeditionary Force. In part due to concern about potential casualties from this course of action, the Bush administration approved USCENTCOM commander General Norman Schwarzkopf’s preferred concept for a flanking offensive using two U.S. Army corps and additional Marine forces.[4] Despite major reinforcements and a more imaginative battle plan, USCENTCOM medical personnel reportedly briefed Defense Secretary Dick Cheney and Joint Chiefs Chairman Colin Powell in December 1990 that they were anticipating 20,000 casualties, including 7,000 killed in action.[5] Even as late as mid-February 1991, PERSCOM was forecasting 20,000 U.S. casualties in the first five days of combat.[6]

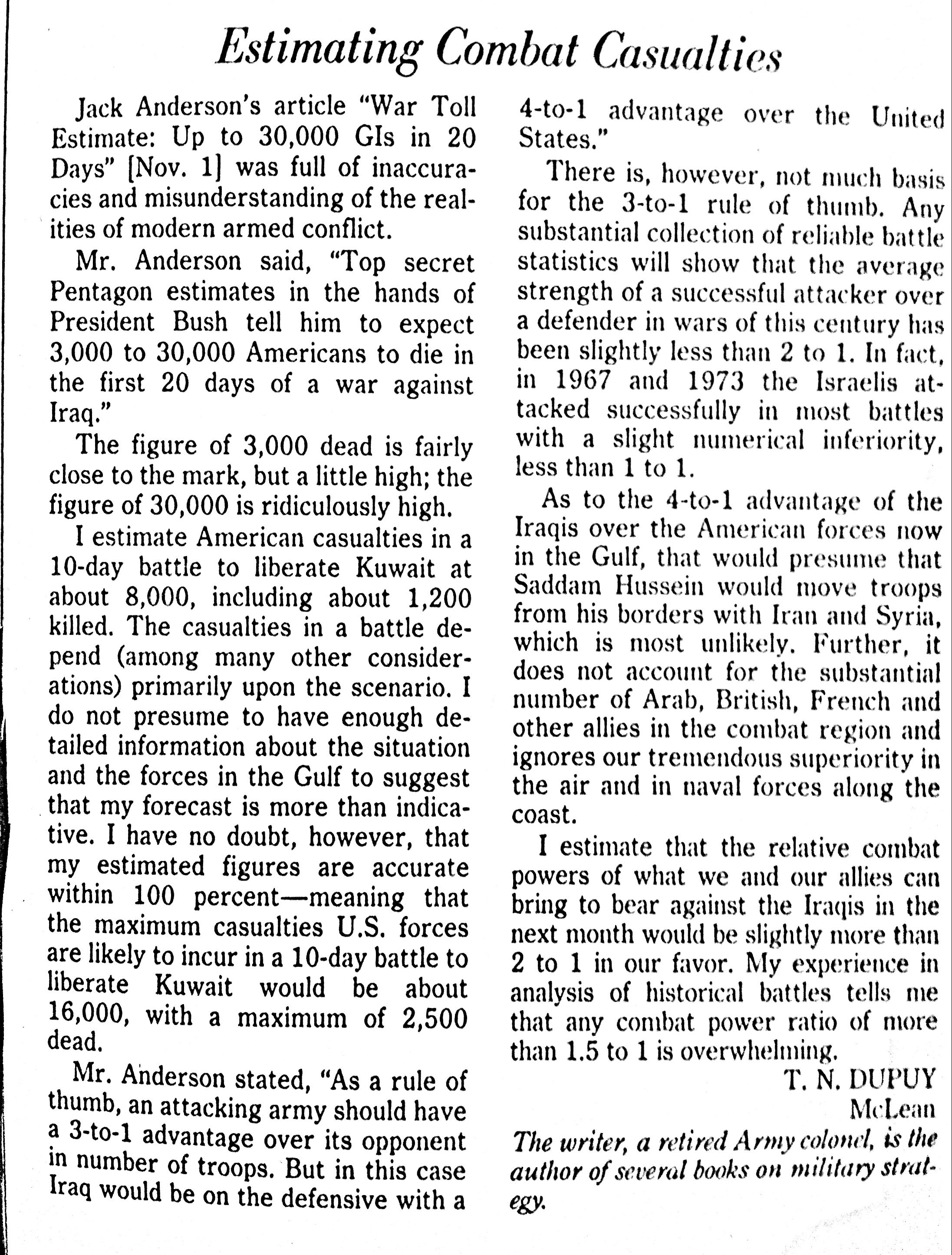

The reported U.S. government casualty estimates prompted various public analysts to offer their own public forecasts. One anonymous “retired general” was quoted as saying “Everyone wants to have the number…Everyone wants to be able to say ‘he’s right or he’s wrong, or this is the way it will go, or this is the way it won’t go, or better yet, the senator or the higher-ranking official is wrong because so-and-so says that the number is this and such.’”[7]

Trevor Dupuy’s forecast was among the first to be cited by the media[8], and he presented it before a hearing of the Senate Armed Services Committee in December.

Other prominent public estimates were offered by political scientists Barry Posen and John J. Mearshimer, and military analyst Joshua Epstein. In November, Posen projected that the Coalition would initiate an air offensive that would quickly gain air superiority, followed by a frontal ground attack lasting approximately 20 days incurring 4,000 (with 1,000 dead) to 10,000 (worst case) casualties. He used the historical casualty rates experienced by Allied forces in Normandy in 1944 and the Israelis in 1967 and 1973 as a rough baseline for his prediction.[9]

Epstein’s prediction in December was similar to Posen’s. Coalition forces would begin with a campaign to obtain control of the air, followed by a ground attack that would succeed within 15-21 days, incurring between 3,000 and 16,000 U.S. casualties, with 1,049-4,136 killed. Like Dupuy, Epstein derived his forecast from a combat model, the Adaptive Dynamic Model.[10]

On the eve of the beginning of the air campaign in January 1991, Mearshimer estimated that Coalition forces would defeat the Iraqis in a week or less and that U.S. forces would suffer fewer than 1,000 killed in combat. Mearshimer’s forecast was based on a qualitative analysis of Coalition and Iraqi forces as opposed to a quantitative one. Although like everyone else he failed to foresee the extended air campaign and believed that successful air/land breakthrough battles in the heart of the Iraqi defenses would minimize casualties, he did fairly evaluate the disparity in quality between Coalition and Iraqi combat forces.[11]

In the aftermath of the rapid defeat of Iraqi forces in Kuwait, the media duly noted the singular accuracy of Mearshimer’s prediction.[12] The relatively disappointing performance of the quantitative models, especially the ones used by the Defense Department, punctuated debates within the U.S. military operations research community over the state of combat modeling. Dubbed “the base of sand problem” by RAND analysts Paul Davis and Donald Blumenthal, serious questions were raised about the accuracy and validity of the methodologies and constructs that underpinned the models.[13] Twenty-five years later, many of these questions remain unaddressed. Some of these will be explored in future posts.

NOTES

[1] “Potential War Casualties Put at 100,000; Gulf crisis: Fewer U.S. troops would be killed or wounded than Iraq soldiers, military experts predict,” Reuters, 5 September 1990; Benjamin Weiser, “Computer Simulations Attempting to Predict the Price of Victory,” Washington Post, 20 January 1991

[2] Brian Shellum, A Chronology of Defense Intelligence in the Gulf War: A Research Aid for Analysts (Washington, D.C.: DIA History Office, 1997), p. 20

[3] John Brinkerhoff and Theodore Silva, The United States Army Reserve in Operation Desert Storm: Personnel Services Support (Alexandria, VA: ANDRULIS Research Corporation, 1995), p. 9, cited in Brian L. Hollandsworth, “Personnel Replacement Operations during Operations Desert Storm and Desert Shield” Master’s Thesis (Ft. Leavenworth, KS: U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 2015), p. 15

[4] Richard M. Swain, “Lucky War”: Third Army in Desert Storm (Ft. Leavenworth, KS: U.S. Army Command and General Staff College Press, 1994)

[5] Bob Woodward, The Commanders (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1991)

[6] Swain, “Lucky War”, p. 205

[7] Weiser, “Computer Simulations Attempting to Predict the Price of Victory”

[8] “Potential War Casualties Put at 100,000,” Reuters

[9] Barry R. Posen, “Political Objectives and Military Options in the Persian Gulf,” Defense and Arms Control Studies Working Paper, Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, November 1990)

[10] Joshua M. Epstein, “War with Iraq: What Price Victory?” Briefing Paper, Brookings Institution, December 1990, cited in Michael O’Hanlon, “Estimating Casualties in a War to Overthrow Saddam,” Orbis, Winter 2003; Weiser, “Computer Simulations Attempting to Predict the Price of Victory”

[11] John. J. Mearshimer, “A War the U.S. Can Win—Decisively,” Chicago Tribune, 15 January 1991

[12] Mike Royko, “Most Experts Really Blew It This Time,” Chicago Tribune, 28 February 1991

[13] Paul K. Davis and Donald Blumenthal, “The Base of Sand Problem: A White Paper on the State of Military Combat Modeling” (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 1991)

![Photograph of Russian T-90 tank following a hit by a U.S.-made TOW missile in Syria. [War Is Boring.com]](https://dupuyinstitute.dreamhosters.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/t_907.jpg)

A number of forecasts of potential U.S. casualties in a war to evict Iraqi forces from Kuwait appeared in the media in the autumn of 1990. The question of the human costs became a political issue for the administration of George H. W. Bush and influenced strategic and military decision-making.

A number of forecasts of potential U.S. casualties in a war to evict Iraqi forces from Kuwait appeared in the media in the autumn of 1990. The question of the human costs became a political issue for the administration of George H. W. Bush and influenced strategic and military decision-making.