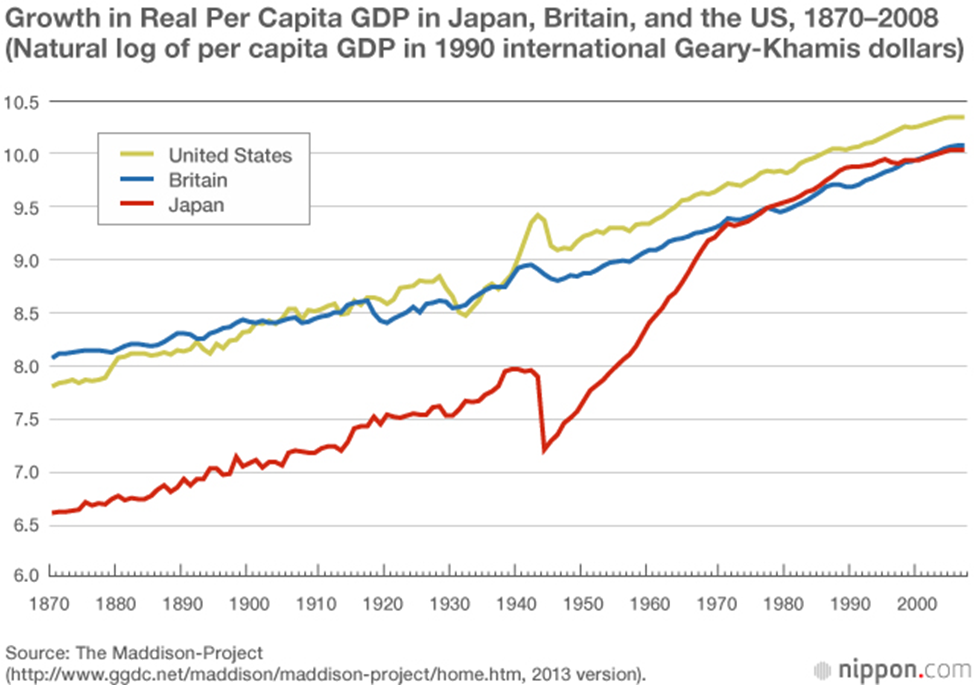

In my previous post, I discussed the progression of aircraft in use by the Japanese Air Self Defense Force (JASDF) since World War II. Japan has also invested significant sums in its domestic aerospace manufacturing capability over this same time period.

Japanese aircraft manufacturing has long been closely tied to the U.S Air Force (USAF) and U.S. aerospace majors offering aircraft for sales, as well as licensed production. Japanese aerospace trade groups categorize this into several distinct phases, including:

- Restarting the aircraft business – starting in 1952 during the Korean War, Japanese aerospace firms like Mitsubishi and Kawasaki reacquired aircraft manufacturing capability by securing contacts with the USAF for maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) of damaged USAF aircraft, including the F-86 Sabre, considered by the Americans to be the star aircraft of the war (although many believe its opponent from the Soviet side, the MiG-15 to have been superior.) There was little doubt, then, that the JASDF would purchase the F-86 and then license its domestic production.

- Licensed production of US military aircraft – “Japan has engaged in licensed production of U.S. state-of-the-art fighter planes, from the F-86 to the F-104, the F-4, and the F-15. Through these projects, the Japanese aircraft industry revived the technical capabilities necessary to domestically manufacture entire aircraft.”

- Domestic military aircraft production – Japanese designed aircraft, while independent, unique designs, also leveraged certain Western designed aircraft as their inspiration, such as the T-1 and eventual F-1 follow-on and the clear resemblance to the British Jaguar. This pattern was repeated in 1987 with the F-2 and its clear design basis on the F-16.

- Domestic Production of business, and civil aircraft – “Japan domestically produces the YS-11 passenger plane as well as the FA-200, MU-2, FA-300, MU-300, BK-117, and other commercial aircraft, and is an active participant in international joint development programs with partners such as the American passenger aircraft manufacturer Boeing.”

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) won a contract to build the wing for the Boeing 787, a job that Boeing now considers a core competency, and is unlikely to outsource again (they kept this task in house for the more recent 737 MAX, and 777X aircraft). This shows MHI’s depth of capability.

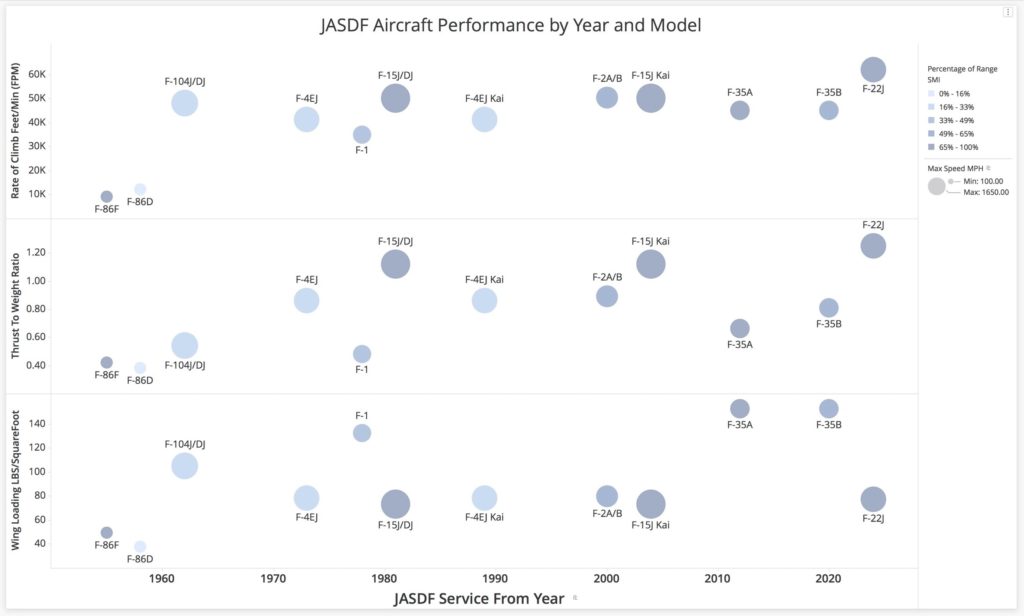

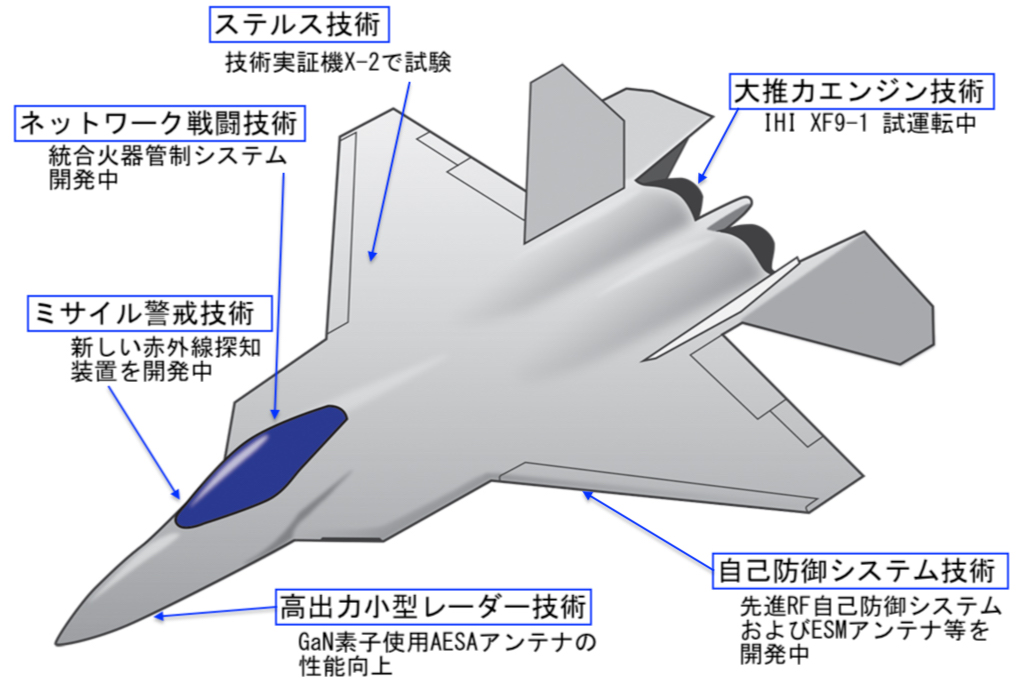

Also in the previous post, I could not help but include the “F-22J,” a hypothetical fighter that has been requested by the Japanese government numerous times, as the air power threat from the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) has grown. The export of the F-22, however, was outlawed by the Obey amendment to the 1998 Defense Authorization Act (a useful summary of this debate is here). So stymied, the JASDF and supporting Ministry of Defense personnel conducted a series of design studies in order to establish detailed requirements. These studies clarified the approach to be taken for the next aircraft to put into service, the F-3 program, ostensibly a successor to the F-2, although the role to be played is more of an air superiority or air dominance fighter, rather than a strike fighter. These studies concluded that range, or endurance is the most important metric for survivability, a very interesting result indeed.

Airframe developers…appear to have settled on something close to the 2013 configuration for the F-3 that emphasized endurance and weapons load over flight performance… That design, 25DMU, described a heavy fighter with a belly weapons bay for six ramjet missiles about the size of the MBDA Meteor. The wing was large and slender by fighter standards, offering high fuel volume and low drag due to lift but penalizing acceleration.… The key factor was that the high-endurance design provided more aircraft on station than would be available from an alternative fleet of high-performance fighters. – (Aviation Week & Space Technology, February 15-28, 2016)

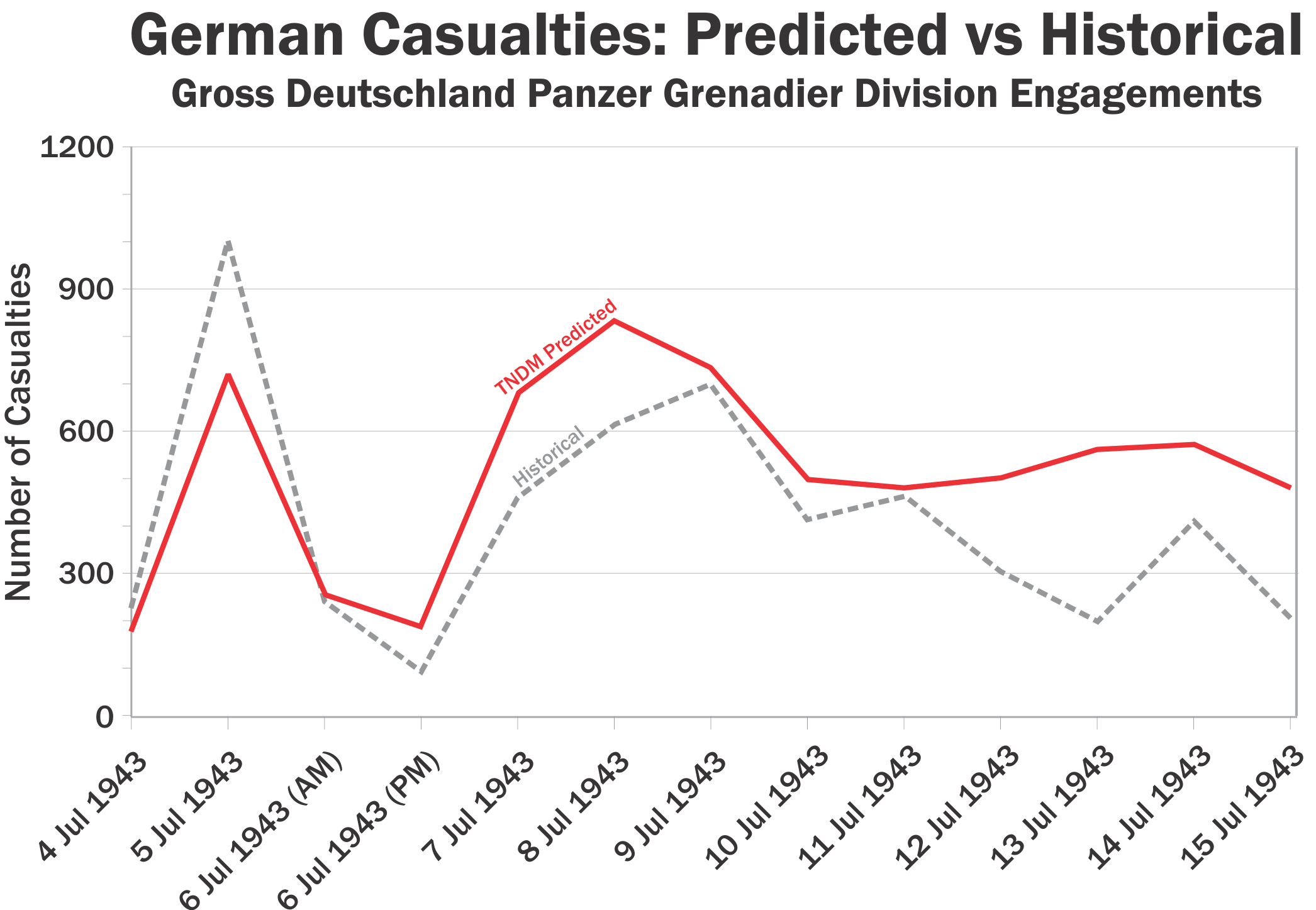

I am curious about the air combat models that reached the conclusion that endurance is the key metric for a new fighter. Similar USAF combat models indicated that in a conflict with PLA armed forces, the USAF would be pushed back to their bases in Japan after the first few days. “In any air war we do great in the first couple of days. Then we have to move everything back to Japan, and we can’t generate sufficient sorties from that point for deep strike on the mainland,” according to Christopher Johnson, former CIA senior China analyst [“The rivals,” The Economist, 20 October 2018]. (History reminds us of aircraft designed for range and maneuverability, the Mitsubishi A6M “Zero,” which also de-emphasized durability, such as pilot armor or self-sealing fuel tanks … was this the best choice?) Validation of combat models with historical combat data seems like an excellent choice if you are investing trillions of Yen, putting the lives of your military pilots on the line, and investing in a platform that will be in service for decades.

Given this expected cost, Japan faces a choice to develop the F-3 independently, or with foreign partners. Mitsubishi built and flew the X-2 “Shinshin” prototype in April 2016. The JASDF also issued an RFP to existing aircraft manufacturers, including the BAE Eurofighter Typhoon, the Boeing F-15 Eagle, and the Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor. In October 2018, the Typhoon and the Eagle were rejected for not meeting the requirements, while the Raptor was rejected because “no clear explanation was given about the possibility of the U.S. government lifting the export ban.” The prospect of funding the entire cost of the F-3 fighter by independently developing the X-2 also does not appear acceptable, so Japan will look for a foreign partner for co-development. There is no shortage of options, from the British, the Franco-Germans, or multiple options with the Americans.