U.S. Army Major Amos Fox, who is quickly establishing himself as one of the brighter sparks analyzing the contemporary Russian way of land warfare, has a new article, “The Russian–Ukrainian War: Understanding the Dust Clouds on the Battlefield,” published by West Point’s Modern War Institute. In it he assesses the linkage between Russian land warfare operations, strategy, and policy.

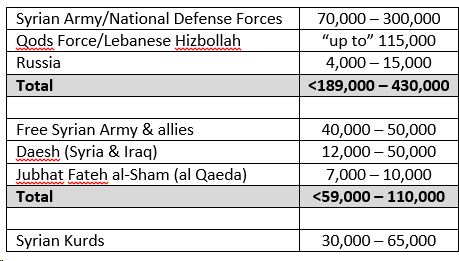

In Fox’s analysis, despite the decisive advantages afforded to the Russian Army and their Ukrainian Separatist proxies through “the employment of the semi-autonomous battalion tactical group, and a reconnaissance-strike model that tightly couples drones to strike assets, hastening the speed at which overwhelming firepower is available to support tactical commanders,” the actual operations executed by these forces should be characterized as classic sieges, as opposed to decisive operational maneuver.

Fox details three operations employing this approach – tactical combat overmatch enabling envelopment and the subsequent application of steady pressure – that produced military success leading directly to political results advantageous to the Russian government.

- The Battle of Ilovaisk in August 2014 led the Ukrainian government to seek negotiations leading to the Minsk Protocol on September 5, 2014.

- The Second Battle of Donetsk Airport from September 2014 to January 2015, which inflicted substantial casualties and equipment losses on the Ukrainian Army.

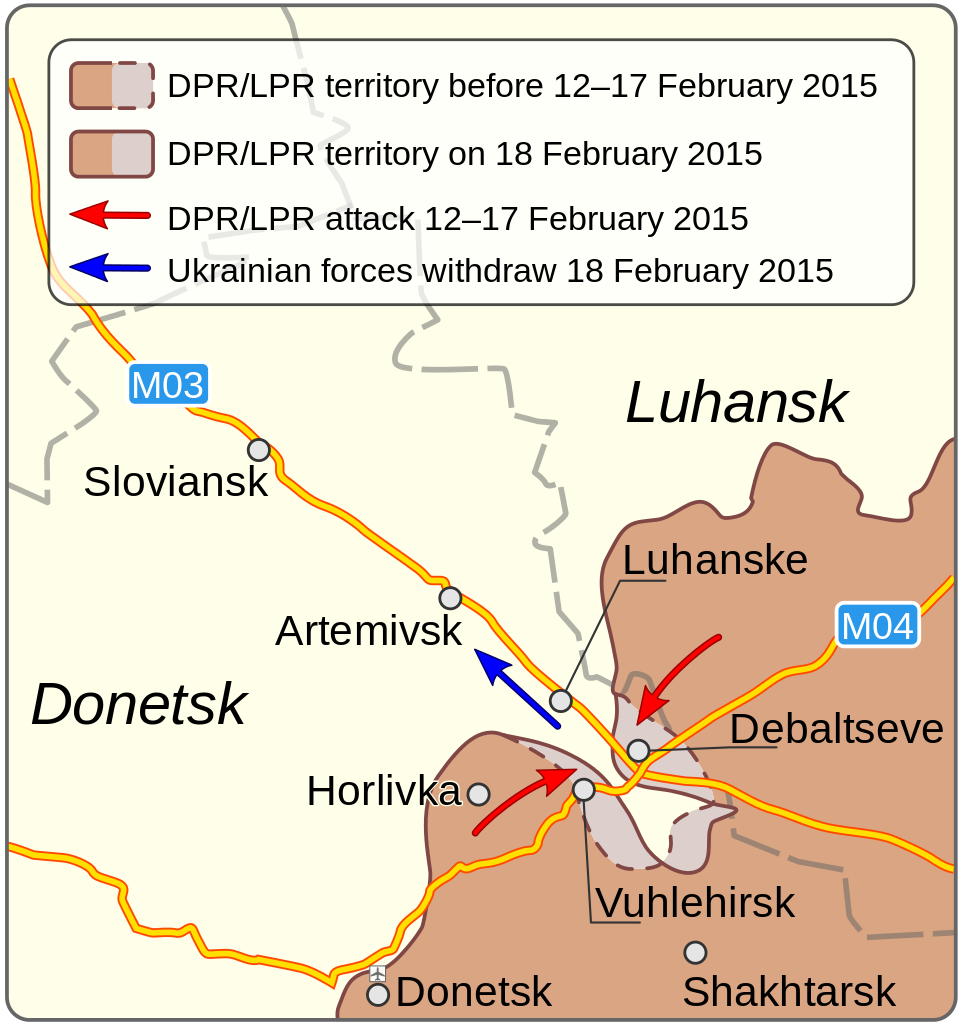

- The Battle of Debal’tseve in January-February 2015, which inflicted further military and civilian losses on the Ukrainians and triggered the Minsk II agreement.

According to Fox, the military strategy of siege operations effectively enabled the limited political goals of the Russian government.

What explains Russia’s evident preference for the siege? Would it not make more sense to quickly annihilate the Ukrainians? Perhaps. However, the siege’s benefit is its ability to transfer military power into political progress, while obfuscating the associated costs. A rapid, violent, decisive victory in which hundreds of Ukrainian soldiers are killed in a matter of days is counterproductive to Russia’s political goals, whereas the incremental use of violence over time accomplishes the same objectives with less disturbance to the international community.

Fox believes that this same operational concept was applied by the Syrian Army and its Russian enablers to capture the city of Aleppo last month, albeit with somewhat different tactics, such as substituting airstrikes for long-range artillery and rockets.

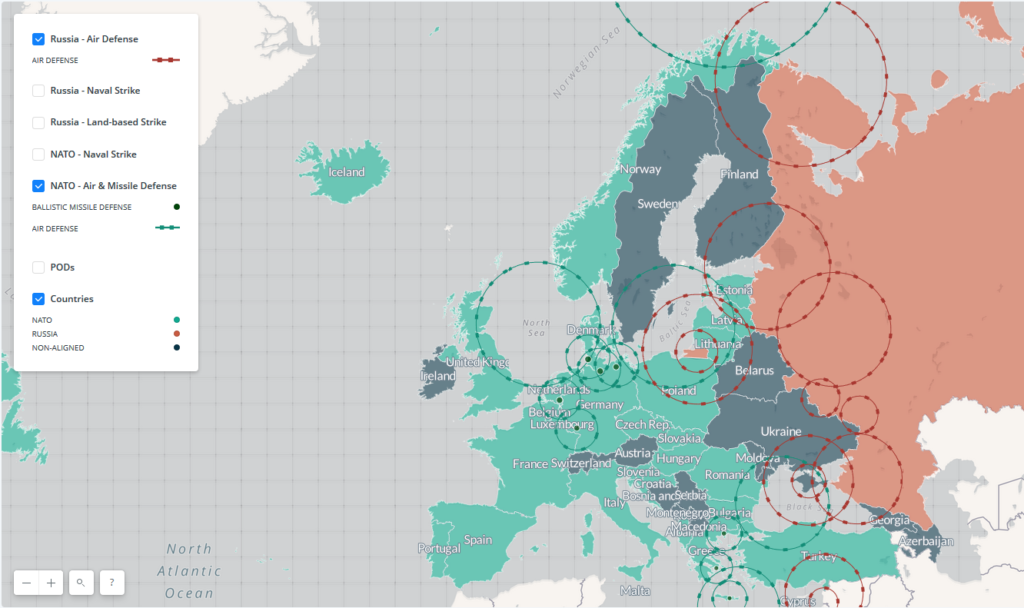

He advises that the U.S. would be prudent to plan for and prepare to face the new Russian land warfare capabilities.

These new features of Russian warfare—and an understanding of them in the context of that warfare’s very conventional character—should inform US planning. The contemporary Russian army is combat-experienced in combined arms maneuver at all echelons of command, a skill that the US Army is still working to recover after well over a decade of counterinsurgency operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. This fact could prove troublesome if Russia elects to push further in Europe, infringing upon NATO partners, or if US and Russian interests continue to collide in areas like Syria. Preparing to combat Russian cyber threats or hybrid tactics is important. But the lesson from Ukraine is clear: It is equally vital to train and equip US forces to counter the type of conventional capabilities Russia has demonstrated in Ukraine.

UPDATE: An Additional Comment on the Link Between Operations, Strategy, and Policy In Russian Hybrid Warfare

The International Security Studies Forum (ISSF) has posted a

The International Security Studies Forum (ISSF) has posted a