There is a lot of smart writing being published over at The Strategy Bridge. If you don’t follow it, you should. Among the recent offerings is a very good piece by Erik Heftye, a retired Air Force officer and senior military analyst in the U.S. Army’s Mission Command Battle Laboratory at Fort Leavenworth. His article “Multi-Domain Confusion: All Domains Are Not Created Equal,” takes a look at an au courant topic central to the new concept of Multi-Domain Battle (MDB).

Defense grognards have been grumbling that MDB is just a new term for an old concept. This is true, insofar as it goes. I am not sure this is in dispute. After all, the subtitle of the U.S. Army/U.S. Marine Corps MDB white paper is “Combined Arms For The 21st Century.” However, such comments do raise the issue of whether new terms for old concepts are serving to clarify or cloud current understanding.

This is Heftye’s concern regarding the use of the term domain: “An ambiguous categorization of separate operating domains in warfare could actually pose an intractable conceptual threat to an integrated joint force, which is ironically the stated purpose of multi-domain battle.” Noting the vagueness of the concept, Heftye traces how the term entered into U.S. military doctrine in the 1990s and evolved into the current four physical (land, sea, air, and space) and one virtual (cyberspace) warfighting realms. He then discusses the etymology of the word and how its meanings imply that all of the domains are equivalent in nature and importance. While this makes sense for air, sea, and land, the physical aspects of those domains do not translate to space or cyberspace. He argues that treating them all analogously will inevitably lead to conceptual confusion.

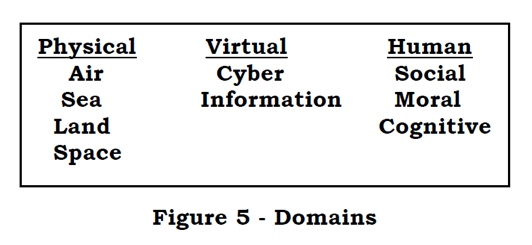

Heftye recommends a solution: “In order to minimize the problem of domain equivalence, a revised construct should distinguish different types of domains in relation to relevant and advantageous warfighting effects. Focusing on effects rather than domains would allow for the elimination of unnecessary bureaucratic seams, gaps, and turf wars.” He offers up a simplified variation of the domain construct that had been published in the superseded 2005 edition of the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s Capstone Concept for Joint Operations, which defined a domain as “any potential operating ‘space’ through which the target system can be influenced—not only the domains of land, sea, air, and space, but also the virtual (information and cyber) and human (cognitive, moral, and social) domains.”

This version not only simplifies by cutting the five existing categories to three, but it also groups like with like. “Land, sea, air, and space are physical domains involving material reality. Cyberspace and information, as well as the electromagnetic spectrum are virtual domains involving sensing and perception. The construct also included a human category involving value judgements.” Heftye acknowledges that looking at domains in terms of effects runs contrary to then-Joint Forces Commander General (and current Defense Secretary) James Mattis’s ban on the use of the Effects Based Operations (EBO) concept by the U.S. military 2008. He also points out that the concept of domains will not be going away anytime soon, either.

Of course, conceptual confusion is not a unique problem in U.S. military doctrine argues Steve Leonard in “Broken and Unreadable: Our Unbearable Aversion to Doctrine,” over at the Modern War Institute at West Point (which is also publishing great material these days). Leonard (aka Doctrine Man!!), a former U.S. Army senior strategist, ruminates about dissatisfaction and discontent with the American “rules of the game.” He offers up a personal anecdote about a popular military staff pastime: defining doctrinal terms.

We also tend to over-define our terminology. Words in common usage since the days of Noah Webster can find new life—and new meaning—in Army doctrine. Several years ago, I endured an hours-long argument among a group of doctrine writers trying to define the term “asymmetric.” The suggestion—after three full hours of debate—that the group consult a dictionary was not well-received.

I have no doubt Erik Heftye feels your pain, Doctrine Man.