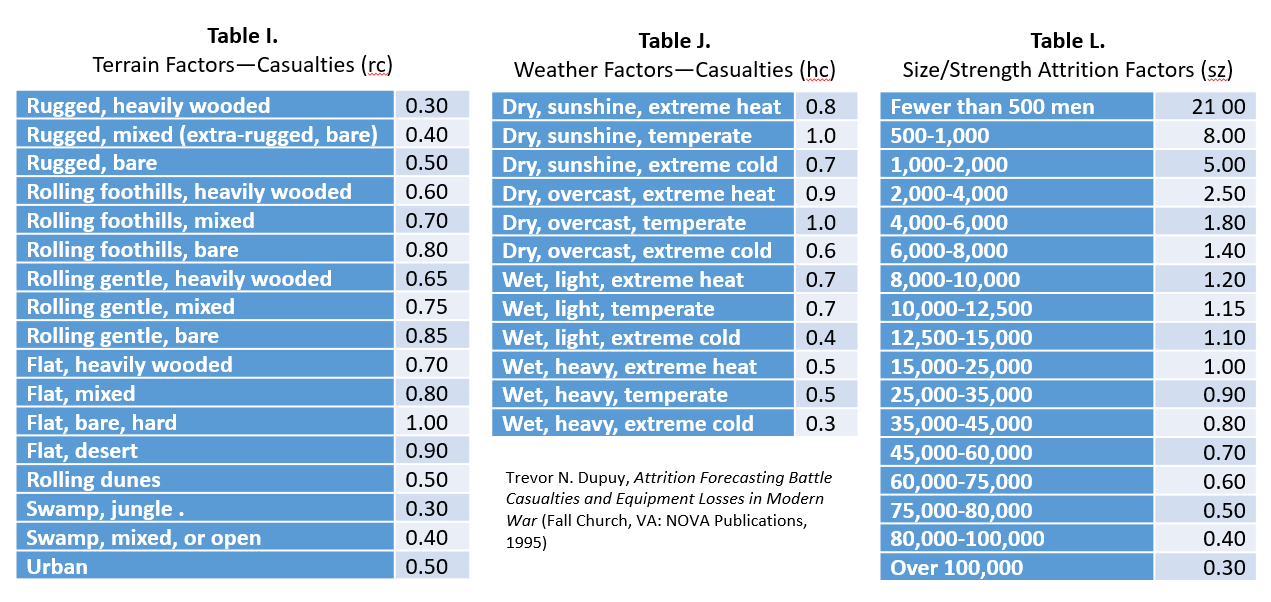

Trevor Dupuy thought that it was possible to identify and quantify the effects of some individual moral and behavioral (i.e. human) factors on combat. He also believed that many of these factors interacted with each other and with environmental and operational (i.e. physical) variables in combat as well, although parsing and quantifying these effects was a good deal more difficult. Among the combat phenomena he considered to be the result of interaction with human factors were:

- Interaction of Firepower, Mobility, Dispersion

- Combat Intensity

- Friction

- Defensive Posture

- Momentum

- Time & Space

- Chance

Dupuy was critical of combat models and simulations that failed to address these relationships. The prevailing approach to the design of combat modeling used by the U.S. Department of Defense is known as the aggregated, hierarchical, or “bottom-up” construct. Bottom-up models generally use the Lanchester equations, or some variation on them, to calculate combat outcomes between individual soldiers, tanks, airplanes, and ships. These results are then used as inputs for models representing warfare at the brigade/division level, the outputs of which are then fed into theater-level simulations. Many in the American military operations research community believe bottom-up models to be the most realistic method of modeling combat.

Dupuy criticized this approach for many reasons (including the inability of the Lanchester equations to accurately replicate real-world combat outcomes), but mainly because it failed to represent human factors and their interactions with other combat variables.

It is almost undeniable that there must be some interaction among and within the effects of physical as well as behavioral variable factors. I know of no way of measuring this. One thing that is reasonably certain is that the use of the bottom-up approach to model design and development cannot capture such interactions. (Most models in use today are bottom-up models, built up from one-on-one weapons interactions to many-on-many.) Presumably these interactions are captured in a top-down model derived from historical experience, of which there is at least one in existence [by which, Dupuy meant his own].

Dupuy was convinced that any model of combat that failed to incorporate human factors would invariably be inaccurate, which put him at odds with much of the American operations research community.

War does not consist merely of a number of duels. Duels, in fact, are only a very small—though integral—part of combat. Combat is a complex process involving interaction over time of many men and numerous weapons combined in a great number of different, and differently organized, units. This process cannot be understood completely by considering the theoretical interactions of individual men and weapons. Complete understanding requires knowing how to structure such interactions and fit them together. Learning how to structure these interactions must be based on scientific analysis of real combat data.[1]

While this unresolved debate went dormant some time ago, bottom-up models became the simulations of choice in Defense Department campaign planning and analysis. It should be noted, however, that the Defense Department disbanded its campaign-level modeling capabilities in 2011 because the use of the simulations in strategic analysis was criticized as “slow, manpower-intensive, opaque, difficult to explain because of its dependence on complex models, inflexible, and weak in dealing with uncertainty.”

NOTES

[1] Trevor N. Dupuy, Understanding War: History and Theory of Combat (New York: Paragon House, 1987), p. 195.