In an article published by West Point’s Modern War Institute last month, “The US Army is Wrong on Future War,” Nathan Jennings, Amos Fox and Adam Taliaferro laid out a detailed argument that current and near-future political, strategic, and operational realities augur against the Army’s current doctrinal conceptualization for Multi-Domain Operations (MDO).

[T]he US Army is mistakenly structuring for offensive clashes of mass and scale reminiscent of 1944 while competitors like Russia and China have adapted to twenty-first-century reality. This new paradigm—which favors fait accompli acquisitions, projection from sovereign sanctuary, and indirect proxy wars—combines incremental military actions with weaponized political, informational, and economic agendas under the protection of nuclear-fires complexes to advance territorial influence…

These factors suggest, cumulatively, that the advantage in military confrontation between great powers has decisively shifted to those that combine strategic offense with tactical defense.

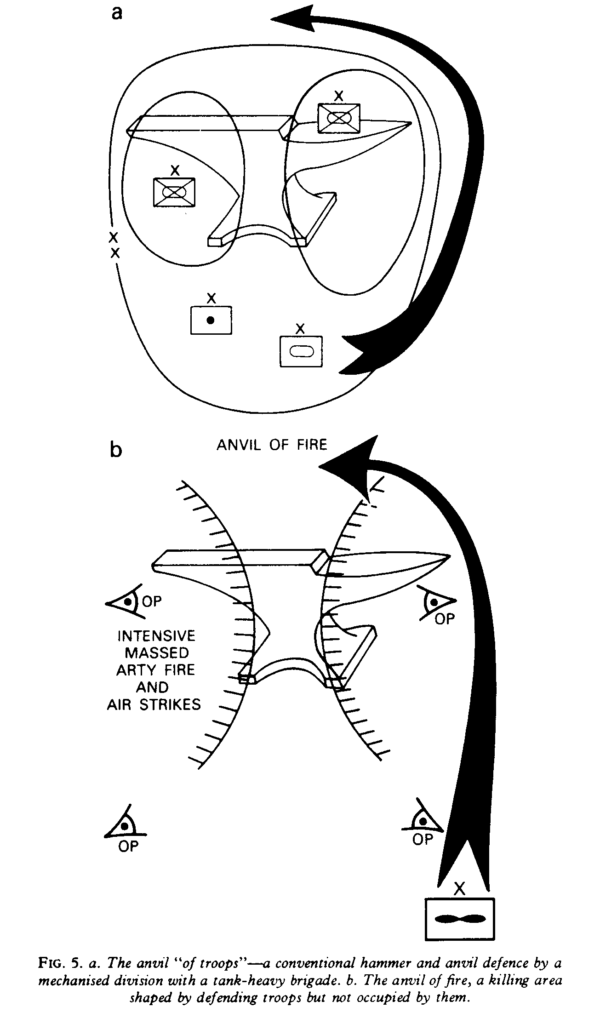

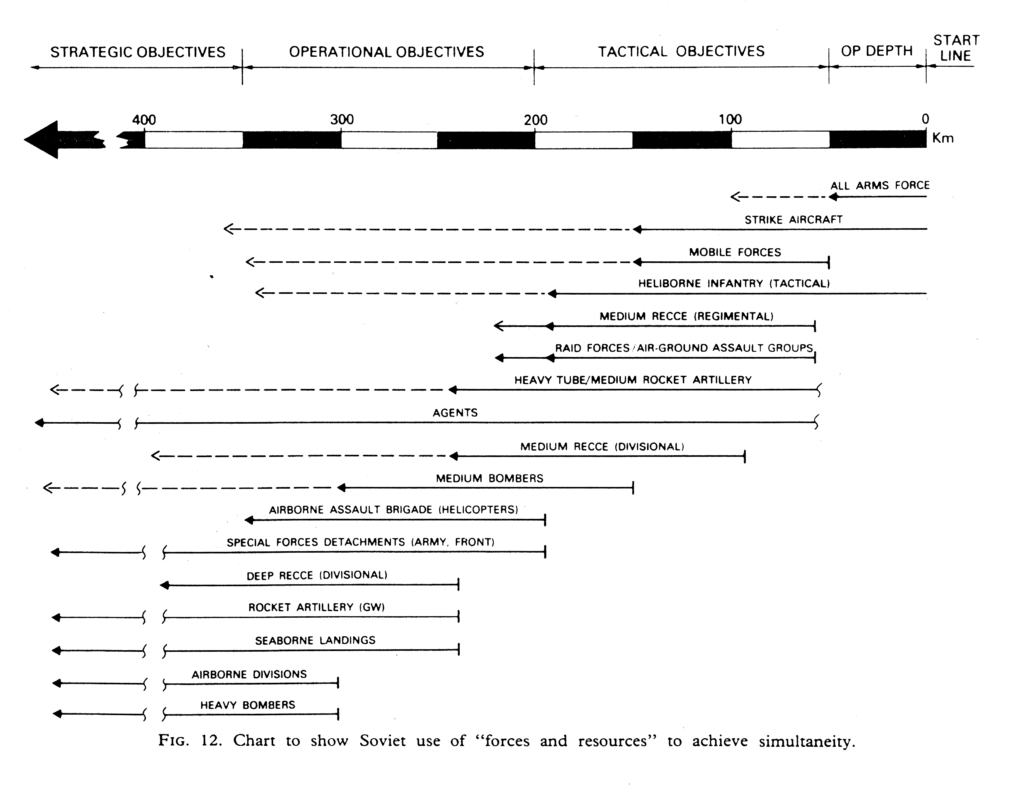

As a consequence, the authors suggested that “the US Army should recognize the evolved character of modern warfare and embrace strategies that establish forward positions of advantage in contested areas like Eastern Europe and the South China Sea. This means reorganizing its current maneuver-centric structure into a fires-dominant force with robust capacity to defend in depth.”

Forward Defense, Active Defense, and AirLand Battle

To illustrate their thinking, Jennings, Fox, and Taliaferro invoked a specific historical example:

This strategic realignment should begin with adopting an approach more reminiscent of the US Army’s Active Defense doctrine of the 1970s than the vaunted AirLand Battle concept of the 1980s. While many distain (sic) Active Defense for running counter to institutional culture, it clearly recognized the primacy of the combined-arms defense in depth with supporting joint fires in the nuclear era. The concept’s elevation of the sciences of terrain and weaponry at scale—rather than today’s cult of the offense—is better suited to the current strategic environment. More importantly, this methodology would enable stated political aims to prevent adversary aggression rather than to invade their home territory.

In the article’s comments, many pushed back against reviving Active Defense thinking, which has apparently become indelibly tarred with the derisive criticism that led to its replacement by AirLand Battle in the 1980s. As the authors gently noted, much of this resistance stemmed from the perceptions of Army critics that Active Defense was passive and defensively-oriented, overly focused on firepower, and suspicions that it derived from operations research analysts reducing warfare and combat to a mathematical “battle calculus.”

While AirLand Battle has been justly lauded for enabling U.S. military success against Iraq in 1990-91 and 2003 (a third-rank, non-nuclear power it should be noted), it always elided the fundamental question of whether conventional deep strikes and operational maneuver into the territory of the Soviet Union’s Eastern European Warsaw Pact allies—and potentially the Soviet Union itself—would have triggered a nuclear response. The criticism of Active Defense similarly overlooked the basic political problem that led to the doctrine in the first place, namely, the need to provide a credible conventional forward defense of West Germany. Keeping the Germans actively integrated into NATO depended upon assurances that a Soviet invasion could be resisted effectively without resorting to nuclear weapons. Indeed, the political cohesion of the NATO alliance itself rested on the contradiction between the credibility of U.S. assurances that it would defend Western Europe with nuclear weapons if necessary and the fears of alliance members that losing a battle for West Germany would make that necessity a reality.

Forward Defense in Eastern Europe

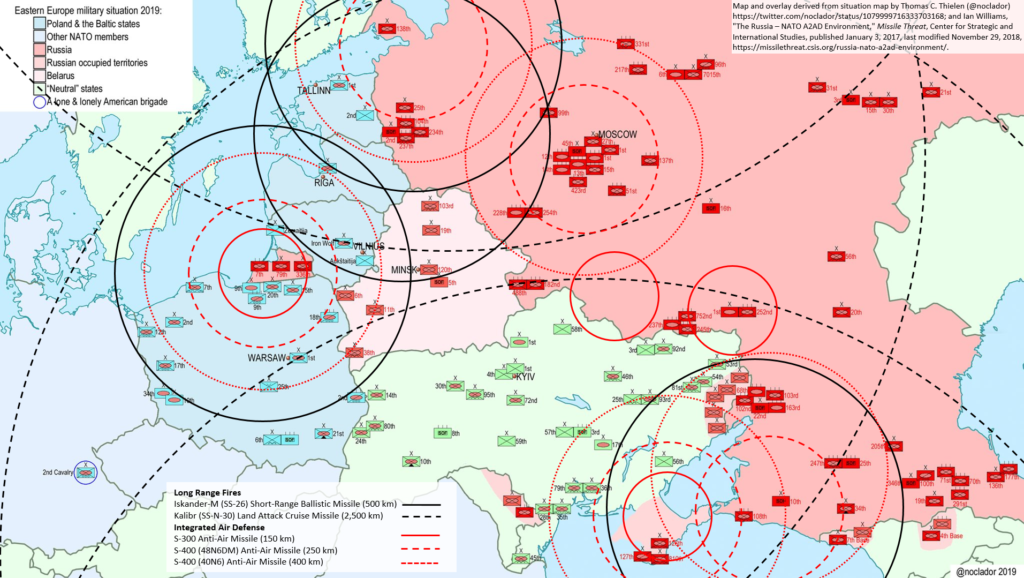

A cursory look at the current military situation in Eastern Europe along with Russia’s increasingly robust anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities (see map) should clearly illustrate the logic behind a doctrine of forward defense. U.S. and NATO troops based in Western Europe would have to run a gauntlet of well protected long-range fires systems just to get into battle in Ukraine or the Baltics. Attempting operational maneuver at the end of lengthy and exposed logistical supply lines would seem to be dauntingly challenging. The U.S. 2nd U.S. Cavalry ABCT Stryker Brigade Combat Team based in southwest Germany appears very much “lone and lonely.” It should also illustrate the difficulties in attacking the Russian A2/AD complex; an act, which Jennings, Fox, and Taliaferro remind, that would actively court a nuclear response.

In this light, Active Defense—or better—a MDO doctrine of forward defense oriented on “a fires-dominant force with robust capacity to defend in depth,” intended to “enable stated political aims to prevent adversary aggression rather than to invade their home territory,” does not really seem foolishly retrograde after all.

With the December 2018 update of the U.S. Army’s Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) concept, this seems like a good time to review the evolution of doctrinal thinking about it. We will start with the event that sparked the Army’s thinking about the subject: the 2014 rocket artillery barrage fired from Russian territory that devastated Ukrainian Army forces near the village of Zelenopillya. From there we will look at the evolution of Army thinking beginning with the initial draft of an operating concept for Multi-Domain Battle (MDB) in 2017. To conclude, we will re-up two articles expressing misgivings over the manner with which these doctrinal concepts are being developed, and the direction they are taking.

With the December 2018 update of the U.S. Army’s Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) concept, this seems like a good time to review the evolution of doctrinal thinking about it. We will start with the event that sparked the Army’s thinking about the subject: the 2014 rocket artillery barrage fired from Russian territory that devastated Ukrainian Army forces near the village of Zelenopillya. From there we will look at the evolution of Army thinking beginning with the initial draft of an operating concept for Multi-Domain Battle (MDB) in 2017. To conclude, we will re-up two articles expressing misgivings over the manner with which these doctrinal concepts are being developed, and the direction they are taking.

[This piece was originally posted on 13 July 2016.]

[This piece was originally posted on 13 July 2016.]