The ninth of Trevor Dupuy’s Timeless Verities of Combat is:

Superior Combat Power Always Wins.

From Understanding War (1987):

Military history demonstrates that whenever an outnumbered force was successful, its combat power was greater than that of the loser. All other things being equal, God has always been on the side of the heaviest battalions and always will be.

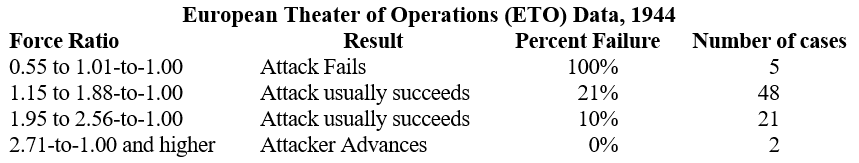

In recent years two or three surveys of modern historical experience have led to the finding that relative strength is not a conclusive factor in battle outcome. As we have seen, a superficial analysis of historical combat could support this conclusion. There are a number of examples of battles won by the side with inferior numbers. In many battles, outnumbered attackers were successful.

These examples are not meaningful, however, until the comparison includes the circumstances of the battles and opposing forces. If one take into consideration surprise (when present), relative combat effectiveness of the opponents, terrain features, and the advantage of defensive posture, the result may be different. When all of the circumstances are quantified and applied to the numbers of troops and weapons, the side with the greater combat power on the battlefield is always seen to prevail.

The concept of combat power is foundational to Dupuy’s theory of combat. He did not originate it; the notion that battle encompasses something more than just “physics-based” aspects likely originated with British theorist J.F.C. Fuller during World War I and migrated into U.S. Army thinking via post-war doctrinal revision. Dupuy refined and sharpened the Army’s vague conceptualization of it in the first iterations of his Quantified Judgement Model (QJM) developed in the 1970s.

Dupuy initially defined his idea of combat power in formal terms, as an equation in the QJM:

P = (S x V x CEV)

When:

P = Combat Power

S = Force Strength

V = Environmental and Operational Variable Factors

CEV = Combat Effectiveness Value

Essentially, combat power is the product of:

- force strength as measured in his models through the Theoretical/Operational Lethality Index (TLI/OLI), a firepower scoring method for comparing the lethality of weapons relative to each other;

- the intangible environmental and operational variables that affect each circumstance of combat; and

- the intangible human behavioral (or moral) factors that determine the fighting quality of a combat force.

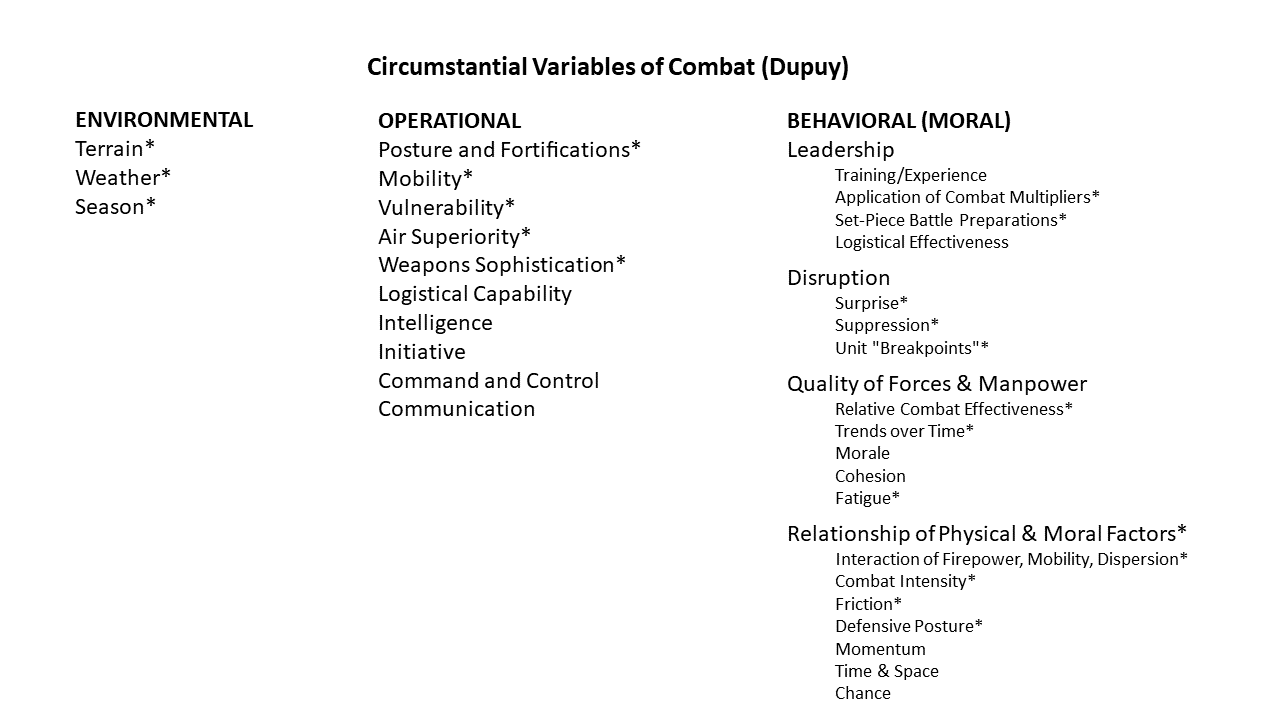

Dupuy’s theory of combat power and its functional realization in his models have two virtues. First, unlike most existing combat models, it incorporates the effects of those intangible factors unique to each engagement or battle that influence combat outcomes, but are not readily measured in physical terms. As Dupuy argued, combat consists of more than duels between weapons systems. A list of those factors can be found below.

Second, the analytical research in real-world combat data done by him and his colleagues allowed him to begin establishing the specific nature combat processes and their interaction that are only abstracted in other combat theories and models. Those factors and processes for which he had developed a quantification hypothesis are denoted by an asterisk below.

Today’s edition of TDI Friday Read is a roundup of posts by TDI President Christopher Lawrence exploring the details of tank combat between German and Soviet forces

Today’s edition of TDI Friday Read is a roundup of posts by TDI President Christopher Lawrence exploring the details of tank combat between German and Soviet forces

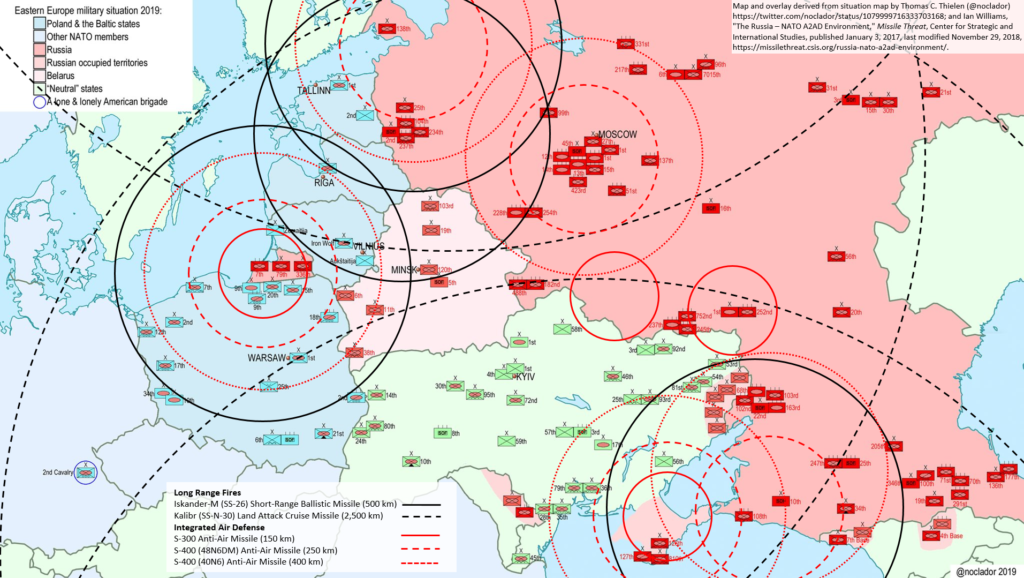

With the December 2018 update of the U.S. Army’s Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) concept, this seems like a good time to review the evolution of doctrinal thinking about it. We will start with the event that sparked the Army’s thinking about the subject: the 2014 rocket artillery barrage fired from Russian territory that devastated Ukrainian Army forces near the village of Zelenopillya. From there we will look at the evolution of Army thinking beginning with the initial draft of an operating concept for Multi-Domain Battle (MDB) in 2017. To conclude, we will re-up two articles expressing misgivings over the manner with which these doctrinal concepts are being developed, and the direction they are taking.

With the December 2018 update of the U.S. Army’s Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) concept, this seems like a good time to review the evolution of doctrinal thinking about it. We will start with the event that sparked the Army’s thinking about the subject: the 2014 rocket artillery barrage fired from Russian territory that devastated Ukrainian Army forces near the village of Zelenopillya. From there we will look at the evolution of Army thinking beginning with the initial draft of an operating concept for Multi-Domain Battle (MDB) in 2017. To conclude, we will re-up two articles expressing misgivings over the manner with which these doctrinal concepts are being developed, and the direction they are taking.