Small Wars Journal has published an article I wrote, titled “Manpower and Counterinsurgency.”

Small Wars Journal has published an article I wrote, titled “Manpower and Counterinsurgency.”

SWJ is a great site for all things related to irregular warfare and more, and a must-read for me. Check it out.

Excellence in Historical Research and Analysis

Excellence in Historical Research and Analysis

Small Wars Journal has published an article I wrote, titled “Manpower and Counterinsurgency.”

Small Wars Journal has published an article I wrote, titled “Manpower and Counterinsurgency.”

SWJ is a great site for all things related to irregular warfare and more, and a must-read for me. Check it out.

Cheng Lai Ki, a student in International Intelligence and Security at King’s College London reviewed America’s Modern Wars for Strife, the War Studies Department blog.

Cheng Lai Ki, a student in International Intelligence and Security at King’s College London reviewed America’s Modern Wars for Strife, the War Studies Department blog.

Keying off Shawn’s previous post…if the DOD figures are accurate this means:

It appears that there are some bad estimates being made here. Nothing wrong with doing an estimate, but something is very wrong if you are doing estimates that are significantly off. Some of these appear to be off.

This is, of course, a problem we encountered with Iraq and Afghanistan and is discussed to some extent in my book America’s Modern Wars. It was also a problem with the Soviet Army in World War II, and is something I discuss in some depth in my Kursk book.

It would be useful to develop a set of benchmarks from past wars looking at insurgents killed per sorties, insurgents killed per civilian killed in air operations (an other types of operations), insurgents killed compared to force strength, and so forth.

Over at Foreign Policy, Michah Zenko, a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, has taken a critical look at the estimates of Daesh fighters the U.S. has killed provided by various Department of Defense sources since 2015. Despite several about-faces on a policy of releasing such figures, the lure to do so is powerful because of the impact they have on public opinion.

Zenko notes the inconsistent logic in the the numbers released, the lack of explanation of the methodology at how they were derived, and how denials about their validity undermine the public policy value of providing them in the first place. There is also the problem of acknowledging noncombatant deaths but asserting that only 55 civilians have been killed in over 15,000 confirmed airstrikes.

Here is the list Zenko compiled of Defense Department cumulative estimates of Daesh fighters killed in Iraq and Syria by U.S. airstrikes:

January 2015: 6,000

March 3, 2015: 8,500

June 1, 2015: ~13,000

July 29, 2015: 15,000

October 12, 2015: 20,000

November 30, 2015: 23,000

January 6, 2016: 25,500

April 12, 2016: 25-26,000

August 10, 2016: 45,000

Chris cited an article two weeks ago in the New York Times, that provided an estimate by a Defense Department source that there are currently 19-25,000 Daesh fighters in Iraq and Syria.

Just a few comments on this article:

Anyhow, interesting blast from the past, although some of this discussion we were also conducting a little over a week ago at a presentation we provided.

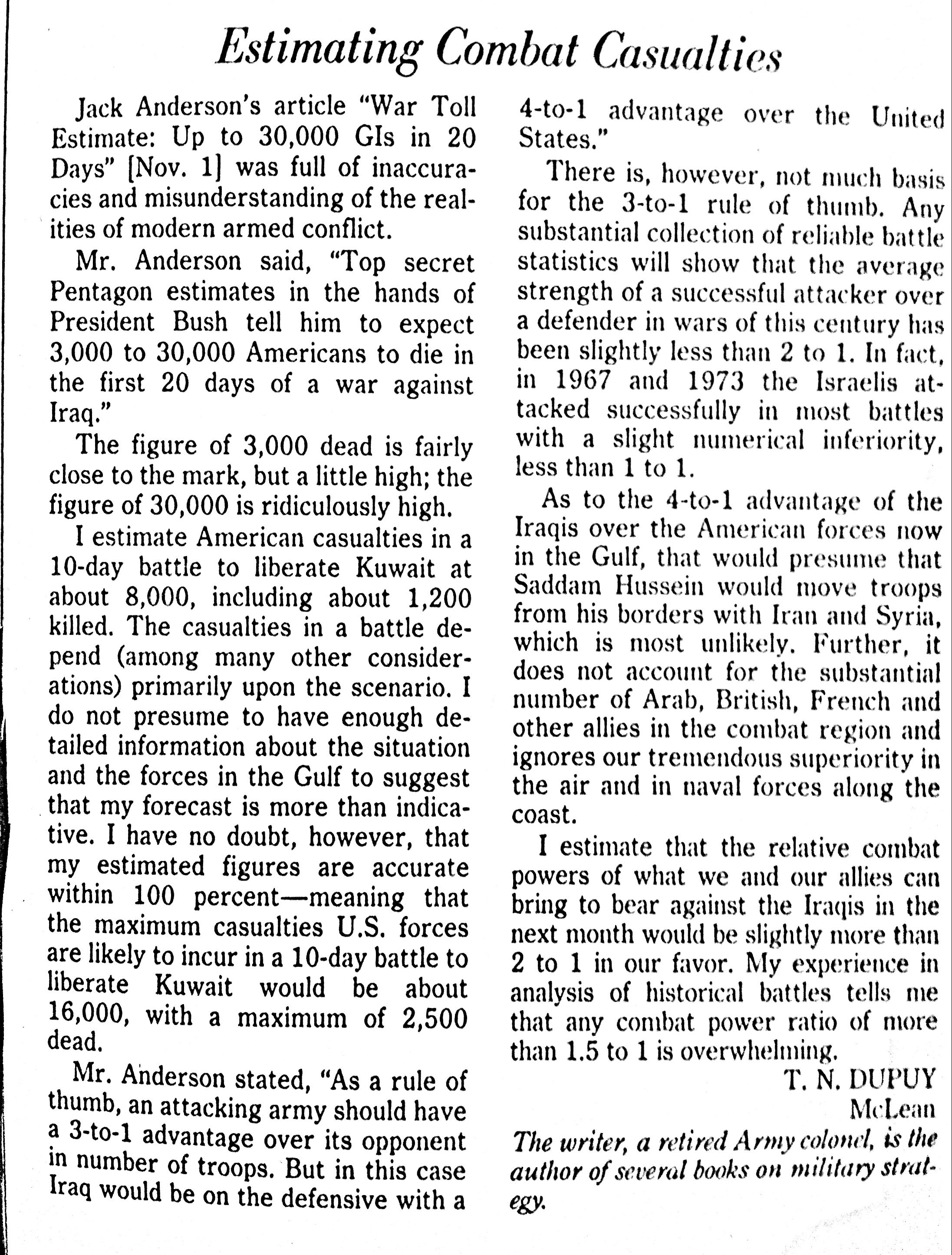

Shawn Woodford was recently browsing in a used bookstore in Annapolis. He came across a copy of Genius for War. Tucked in the front cover was this clipping from the Washington Post. It is undated, but makes reference to a Jack Anderson article from 1 November, presumably 1990. So it must have been published sometime shortly thereafter.

Is it possible for an outside country to build an effective indigenous military? The United States inter-agency and national security communities have a strong current interest in helping other countries develop and sustain effective security establishments. This is officially termed Security Cooperation (SC). The assistance provided directly by the U.S. military to foreign military organizations is called Security Force Assistance (SFA). SC and SFA are both integral aspects of current U.S. foreign policy and military strategy.

The U.S. has been providing SFA since at least World War II, but its success in this undertaking has been decidedly mixed. A two-decade effort by the U.S. to build an effective South Vietnamese army culminated in abject failure at the hands of North Vietnam in 1975. Despite a decade of investment in money, resources, and manpower, the U.S. has yet to build (or rebuild) independently effective military establishments in Afghanistan and Iraq.

One consistent factor in each of these cases has been the lack of a stable, effective indigenous government to underpin the military forces. How important is effective governance to successful military establishments? History suggests that it may be integral.

On his wonderful blog, The Best Defense, Tom Ricks recently posed the question “Is the existence of a capable infantry a sign of a strong government bureaucracy?” In his recently published The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Tonio Andrade cited Stephen Morillo’s observation that “strong infantry depends on strong government” to support that assertion that Europe had poor infantry in the 15th century by Chinese standards because of underdeveloped governments.

According to Ricks, Morillo made six implicit points:

Historical experience would suggest not only that capable military forces are reflective of effective governance, but that strong governments are necessary in order to field strong military establishments. This fundamental lesson may be vital to the future success of U.S. SC and SFA efforts.

A number of forecasts of potential U.S. casualties in a war to evict Iraqi forces from Kuwait appeared in the media in the autumn of 1990. The question of the human costs became a political issue for the administration of George H. W. Bush and influenced strategic and military decision-making.

A number of forecasts of potential U.S. casualties in a war to evict Iraqi forces from Kuwait appeared in the media in the autumn of 1990. The question of the human costs became a political issue for the administration of George H. W. Bush and influenced strategic and military decision-making.

Almost immediately following President Bush’s decision to commit U.S. forces to the Middle East in August 1990, speculation appeared in the media about what a war between Iraq and a U.S.-led international coalition might entail. In early September, U.S. News & World Report reported “that the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff and the National Security Council estimated that the United States would lose between 20,000 and 30,000 dead and wounded soldiers in a Gulf war.” The Bush administration declined official comment on these figures at the time, but the media indicated that they were derived from Defense Department computer models used to wargame possible conflict scenarios.[1] The numbers shocked the American public and became unofficial benchmarks in subsequent public discussion and debate.

A Defense Department wargame exploring U.S. options in Iraq had taken place on 25 August, the results of which allegedly led to “major changes” in military planning.[2] Although linking the wargame and the reported casualty estimate is circumstantial, the cited figures were very much in line with other contemporary U.S. military casualty estimates. A U.S. Army Personnel Command [PERSCOM] document that informed U.S. Central Command [USCENTCOM] troop replacement planning, likely based on pre-crisis plans for the defense of Saudi Arabia against possible Iraqi invasion, anticipated “about 40,000” total losses.[3]

These early estimates were very likely to have been based on a concept plan involving a frontal attack on Iraqi forces in Kuwait using a single U.S. Army corps and a U.S. Marine Expeditionary Force. In part due to concern about potential casualties from this course of action, the Bush administration approved USCENTCOM commander General Norman Schwarzkopf’s preferred concept for a flanking offensive using two U.S. Army corps and additional Marine forces.[4] Despite major reinforcements and a more imaginative battle plan, USCENTCOM medical personnel reportedly briefed Defense Secretary Dick Cheney and Joint Chiefs Chairman Colin Powell in December 1990 that they were anticipating 20,000 casualties, including 7,000 killed in action.[5] Even as late as mid-February 1991, PERSCOM was forecasting 20,000 U.S. casualties in the first five days of combat.[6]

The reported U.S. government casualty estimates prompted various public analysts to offer their own public forecasts. One anonymous “retired general” was quoted as saying “Everyone wants to have the number…Everyone wants to be able to say ‘he’s right or he’s wrong, or this is the way it will go, or this is the way it won’t go, or better yet, the senator or the higher-ranking official is wrong because so-and-so says that the number is this and such.’”[7]

Trevor Dupuy’s forecast was among the first to be cited by the media[8], and he presented it before a hearing of the Senate Armed Services Committee in December.

Other prominent public estimates were offered by political scientists Barry Posen and John J. Mearshimer, and military analyst Joshua Epstein. In November, Posen projected that the Coalition would initiate an air offensive that would quickly gain air superiority, followed by a frontal ground attack lasting approximately 20 days incurring 4,000 (with 1,000 dead) to 10,000 (worst case) casualties. He used the historical casualty rates experienced by Allied forces in Normandy in 1944 and the Israelis in 1967 and 1973 as a rough baseline for his prediction.[9]

Epstein’s prediction in December was similar to Posen’s. Coalition forces would begin with a campaign to obtain control of the air, followed by a ground attack that would succeed within 15-21 days, incurring between 3,000 and 16,000 U.S. casualties, with 1,049-4,136 killed. Like Dupuy, Epstein derived his forecast from a combat model, the Adaptive Dynamic Model.[10]

On the eve of the beginning of the air campaign in January 1991, Mearshimer estimated that Coalition forces would defeat the Iraqis in a week or less and that U.S. forces would suffer fewer than 1,000 killed in combat. Mearshimer’s forecast was based on a qualitative analysis of Coalition and Iraqi forces as opposed to a quantitative one. Although like everyone else he failed to foresee the extended air campaign and believed that successful air/land breakthrough battles in the heart of the Iraqi defenses would minimize casualties, he did fairly evaluate the disparity in quality between Coalition and Iraqi combat forces.[11]

In the aftermath of the rapid defeat of Iraqi forces in Kuwait, the media duly noted the singular accuracy of Mearshimer’s prediction.[12] The relatively disappointing performance of the quantitative models, especially the ones used by the Defense Department, punctuated debates within the U.S. military operations research community over the state of combat modeling. Dubbed “the base of sand problem” by RAND analysts Paul Davis and Donald Blumenthal, serious questions were raised about the accuracy and validity of the methodologies and constructs that underpinned the models.[13] Twenty-five years later, many of these questions remain unaddressed. Some of these will be explored in future posts.

NOTES

[1] “Potential War Casualties Put at 100,000; Gulf crisis: Fewer U.S. troops would be killed or wounded than Iraq soldiers, military experts predict,” Reuters, 5 September 1990; Benjamin Weiser, “Computer Simulations Attempting to Predict the Price of Victory,” Washington Post, 20 January 1991

[2] Brian Shellum, A Chronology of Defense Intelligence in the Gulf War: A Research Aid for Analysts (Washington, D.C.: DIA History Office, 1997), p. 20

[3] John Brinkerhoff and Theodore Silva, The United States Army Reserve in Operation Desert Storm: Personnel Services Support (Alexandria, VA: ANDRULIS Research Corporation, 1995), p. 9, cited in Brian L. Hollandsworth, “Personnel Replacement Operations during Operations Desert Storm and Desert Shield” Master’s Thesis (Ft. Leavenworth, KS: U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 2015), p. 15

[4] Richard M. Swain, “Lucky War”: Third Army in Desert Storm (Ft. Leavenworth, KS: U.S. Army Command and General Staff College Press, 1994)

[5] Bob Woodward, The Commanders (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1991)

[6] Swain, “Lucky War”, p. 205

[7] Weiser, “Computer Simulations Attempting to Predict the Price of Victory”

[8] “Potential War Casualties Put at 100,000,” Reuters

[9] Barry R. Posen, “Political Objectives and Military Options in the Persian Gulf,” Defense and Arms Control Studies Working Paper, Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, November 1990)

[10] Joshua M. Epstein, “War with Iraq: What Price Victory?” Briefing Paper, Brookings Institution, December 1990, cited in Michael O’Hanlon, “Estimating Casualties in a War to Overthrow Saddam,” Orbis, Winter 2003; Weiser, “Computer Simulations Attempting to Predict the Price of Victory”

[11] John. J. Mearshimer, “A War the U.S. Can Win—Decisively,” Chicago Tribune, 15 January 1991

[12] Mike Royko, “Most Experts Really Blew It This Time,” Chicago Tribune, 28 February 1991

[13] Paul K. Davis and Donald Blumenthal, “The Base of Sand Problem: A White Paper on the State of Military Combat Modeling” (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 1991)

[NOTE: This post has been edited to more accurately characterize Trevor Dupuy’s public comments on TNDA’s estimates.]

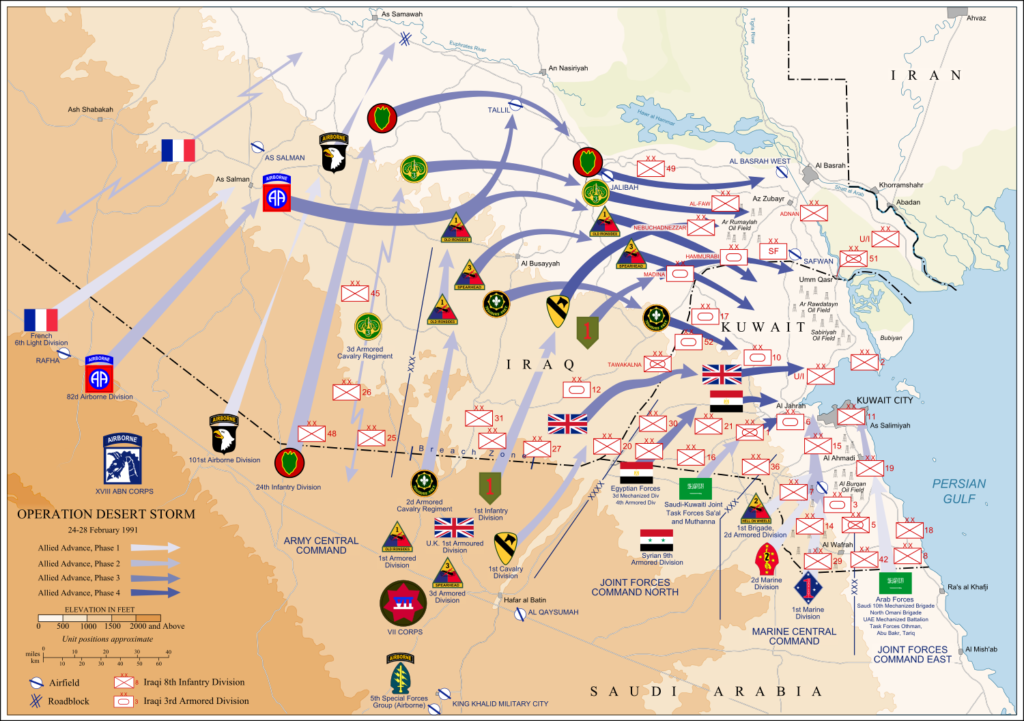

Operation DESERT STORM began on 17 January 1991 with an extended aerial campaign that lasted 38 days. Ground combat operations were initiated on 24 February and concluded after four days and four hours, with U.S. and Coalition forces having routed the Iraqi Army in Kuwait and in position to annihilate surviving elements rapidly retreating northward. According to official accounting, U.S. forces suffered 148 killed in action and 467 wounded in action, for a total of 614 combat casualties. An additional 235 were killed in non-hostile circumstances.[1]

In retrospect, TNDA’s casualty forecasts turned out to be high, with the actual number of casualties falling below the lowest +/- 50% range of estimates. Forecasts, of course, are sensitive to the initial assumptions they are based upon. In public comments made after the air campaign had started but before the ground phase began, Trevor Dupuy forthrightly stated that TNDA’s estimates were likely to be too high.[2]

In a post-mortem on the forecast in March 1991, Dupuy identified three factors which TNDA’s estimates miscalculated:

There were also factors that influenced the outcome that TNDA could not have known beforehand. Its estimates were based on an Iraqi Army force of 480,000, a figure derived from open source reports available at the time. However, the U.S. Air Force’s 1993 Gulf War Air Power Survey, using intelligence collected from U.S. government sources, calculated that there were only 336,000 Iraqi Army troops in and near Kuwait in January 1991 (out of a nominal 540,000) due to unit undermanning and troops on leave. The extended air campaign led a further 25-30% to desert and inflicted about 10% casualties, leaving only 200,000-220,000 depleted and demoralized Iraqi troops to face the U.S. and Coalition ground offensive.[4].

TNDA also underestimated the number of U.S. and Coalition ground troops, crediting them with a total of 435,000, when the actual number was approximately 540,000.[5] Instead of the Iraqi Army slightly outnumbering its opponents in Kuwait as TNDA approximated (480,000 to 435,000), U.S. and Coalition forces probably possessed a manpower advantage approaching 2 to 1 or more at the outset of the ground campaign.

There were some aspects of TNDA’s estimate that were remarkably accurate. Although no one foresaw the 38-day air campaign or the four-day ground battle, TNDA did come quite close to anticipating the overall duration of 42 days.

DESERT STORM as planned and executed also bore a striking resemblance to TNDA’s recommended course of action. The opening air campaign, followed by the “left hook” into the western desert by armored and airmobile forces, coupled with holding attacks and penetration of the Iraqi lines on the Kuwaiti-Saudi border were much like a combination of TNDA’s “Colorado Springs,” “Leavenworth,” and “Siege” scenarios. The only substantive difference was the absence of border raids and the use of U.S. airborne/airmobile forces to extend the depth of the “left hook” rather than seal off Kuwait from Iraq. The extended air campaign served much the same intent as TNDA’s “Siege” concept. TNDA even anticipated the potential benefit of the unprecedented effectiveness of the DESERT STORM aerial attack.

How effective “Colorado Springs” will be in damaging and destroying the military effectiveness of the Iraqi ground forces is debatable….On the other hand, the circumstances of this operation are different from past efforts of air forces to “go it alone.” The terrain and vegetation (or lack thereof) favor air attacks to an exceptional degree. And the air forces will be operating with weapons of hitherto unsuspected accuracy and effectiveness against fortified targets. Given these new circumstances, and considering recent historical examples in the 1967 and 1973 Arab-Israeli Wars, the possibility that airpower alone can cause such devastation, destruction, and demoralization as to destroy totally the effectiveness of the Iraqi ground forces cannot be ignored. [6]

In actuality, the U.S. Central Command air planners specifically targeted Saddam’s government in the belief that air power alone might force regime change, which would lead the Iraqi Army to withdraw from Kuwait. Another objective of the air campaign was to reduce the effectiveness of the Iraqi Army by 50% before initiating the ground offensive.[7]

Dupuy and his TNDA colleagues did anticipate that a combination of extended siege-like assault on Iraqi forces in Kuwait could enable the execution of a quick ground attack coup de grace with minimized losses.

The potential of success for such an operation, in the wake of both air and ground efforts made to reduce the Iraqi capacity for offensive along the lines of either Operation “Leavenworth’…or the more elaborate and somewhat riskier “RazzleDazzle”…would produce significant results within a short time. In such a case, losses for these follow-on ground operations would almost certainly be lower than if they had been launched shortly after the war began.[8]

Unfortunately, TNDA did not hazard a casualty estimate for a potential “Colorado Springs/ Siege/Leavenworth/RazzleDazzle” combination scenario, a forecast for which might very well have come closer to the actual outcome.

Dupuy took quite a risk in making such a prominently public forecast, opening his theories and methodology to criticism and judgement. In my next post, I will examine how it stacked up with other predictions and estimates made at the time.

NOTES

[1] Nese F. DeBruyne and Anne Leland, “American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics,” (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, 2 January 2015), pp. 3, 11

[2] Christopher A. Lawrence, America’s Modern Wars: Understanding Iraq, Afghanistan and Vietnam (Philadelphia, PA: Casemate, 2015) p. 52

[3] Trevor N. Dupuy, “Report on Pre-War Forecasting For Information and Comment: Accuracy of Pre-Kuwait War Forecasts by T.N. Dupuy and HERO-TNDA,” 18 March, 1991. This was published in the April 1991 edition of the online wargaming “fanzine” Simulations Online. The post-mortem also included a revised TNDM casualty calculation for U.S. forces in the ground war phase, using the revised assumptions, of 70 killed and 417 wounded, for a total of 496 casualties. The details used in this revised calculation were not provided in the post-mortem report, so its veracity cannot be currently assessed.

[4] Thomas A. Keaney and Eliot A. Cohen, Gulf War Airpower Survey Summary Report (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Air Force, 1993), pp. 7, 9-10, 107

[5] Keaney and Cohen, Gulf War Airpower Survey Summary Report, p. 7

[6] Trevor N. Dupuy, Curt Johnson, David L. Bongard, Arnold C. Dupuy, How To Defeat Saddam Hussein: Scenarios and Strategies for the Gulf War (New York: Warner Books, 1991), p. 58

[7] Gulf War Airpower Survey, Vol. I: Planning and Command and Control, Pt. 1 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Air Force, 1993), pp. 157, 162-165

[8] Dupuy, et al, How To Defeat Saddam Hussein, p. 114

In my last post on the subject of prediction in security studies, I mentioned that TDI has a public forecasting track record. The first of these, and possibly the most well know, involves the 1990-1991 Gulf War.

On 13 December 1990, Trevor N. Dupuy, President of Trevor N. Dupuy & Associates (TNDA), testified before the House Armed Services Committee on the topic of the looming military confrontation between the military forces of the United States and United Nations Coalition allies and those of Iraq.[1] He offered TNDA’s assessment of the potential character of the forthcoming conflict, as well as estimates of the likely casualties that both sides would suffer. Dupuy published a refined and expanded version of TNDA’s analysis in January 1991.[2]

Based on a methodology derived from Dupuy’s combat models and synthesized data on historical personnel and material combat attrition, TNDA forecast a successful U.S. and Coalition air/ground offensive campaign into Kuwait.[3] Using publicly available sources, TNDA calculated that Iraqi forces in Iraq numbered 480,000, U.S. forces at 310,000, and Coalition allies at 125,000.

The estimated number of casualties varied based on a campaign anticipated to last from 10 to 40 days depending on five projected alternate operational scenarios:

Based on these assumptions, TNDA produced a range of casualty predictions for U.S. forces that TNDA asserted would probably be accurate to within +/- 50%. These ranged from a low of 380 for a 10-day “Colorado Springs” air-only campaign, to a top-end calculation of 16,645 for a 10-day “Colorado Springs” followed by a 20-day “Bulldozer” frontal assault.

TNDA’s Projection of Likely U.S. Casualties

| Scenario | Duration |

Killed |

Wounded |

Total |

+/-50% |

| Colorado Springs |

10-40 days |

190-315 |

190-315 |

380-630 |

— |

| Bulldozer* |

10-20 days |

1,858-2,068 |

8,332-9,222 |

10,190-11,290 |

5,335-16,645 |

| Leavenworth* |

10-20 days |

1,454-1,664 |

6,309-7,199 |

7,763-8,863 |

4,122-12,995 |

| RazzleDazzle* |

10-20 days |

1,319-1,529 |

5,534-6,524 |

6,853-8,053 |

3,717-11,790 |

| Siege* |

10-30 days |

564-1,339 |

1,858-5,470 |

2,422-6,809 |

1,451-10,479 |

* Figures include air casualties

Based on these calculations, TNDA recommended the following course of action:

If the above figures are close to accurate (and history tells us they should should be), then the proper solution is to begin the war with the air campaign of Operation “Colorado Springs.” If this should result in an Iraqi surrender, so much the better. If not, then after about ten days of “Colorado Springs,“ to continue the air campaign for about ten more days while initiating Operation “Siege.” If this does not bring about an Iraqi surrender, the ground campaign should be concluded with Operation “RazzleDazzle.” If this has not brought about an Iraqi surrender, then an advance should be made through the desert to destroy any resisting Iraqi forces and to occupy Baghdad if necessary.[4]

In my next post, I will assess the accuracy of TNDA’s forecast and how it stacked up against others made at the time.

Notes

[1] Armed Services Committee, U.S. House of Representatives, Testimony of Col. T. N. Dupuy, USA, Ret. (Washington D.C.: 13 December 1990)

[2] Trevor N. Dupuy, Curt Johnson, David L. Bongard, Arnold C. Dupuy, If War Comes, How To Defeat Saddam Hussein (McLean, VA.: HERO Books, 1991); subsequently republished as How To Defeat Saddam Hussein: Scenarios and Strategies for the Gulf War (New York: Warner Books, 1991).

[3] These are the Quantified Judgement Model (QJM) and Tactical Numerical Deterministic Model (TNDM). Dupuy’s methodological approach and his first cut on a Gulf War estimate are described in Chapter 7 of Trevor N. Dupuy, Attrition: Forecasting Battle Casualties and Equipment Losses in Modern War (McLean, VA.: HERO Books, 1990).

[4] Dupuy, et al, How To Defeat Saddam Hussein, 126