I updated this post with tables! Click through to the original post and scroll to the bottom.

Excellence in Historical Research and Analysis

Excellence in Historical Research and Analysis

Tag Doctrine

Human Factors In Warfare: Combat Intensity

Trevor Dupuy considered intensity to be another combat phenomena influenced by human factors. The variation in the intensity of combat is an aspect of battle that is widely acknowledged but little studied.

No one who has paid any attention at all to historical combat statistics can have failed to notice that some battles have been very bloody and hard-fought, while others—often under circumstances superficially similar—have reached a conclusion with relatively light casualties on one or both sides. I don’t believe that it is terribly important to find a quantitative reason for such differences, mainly because I don’t think there is any quantitative reason. The differences are usually due to such things as the general circumstances existing when the battles are fought, the personalities of the commanders, and the natures of the missions or objectives of one or both of the hostile forces, and the interactions of these personalities and missions.

From my standpoint the principal reason for trying to quantify the intensity of a battle is for purposes of comparative analysis. Just because casualties are relatively low on one or both sides does not necessarily mean that the battle was not intensive. And if the casualty rates are misinterpreted, then the analysis of the outcome can be distorted. For instance, a battle fought on a flat plain between two military forces will almost invariably have higher casualty rates for both sides than will a battle between those same two forces in mountainous terrain. A battle between those two forces in a heavy downpour, or in cold, wintry weather, will have lower casualties than when the forces are opposed to each other, under otherwise identical circumstances, in good weather. Casualty rates for small forces in a given set of circumstances are invariably higher than the rates for larger forces under otherwise identical circumstances.

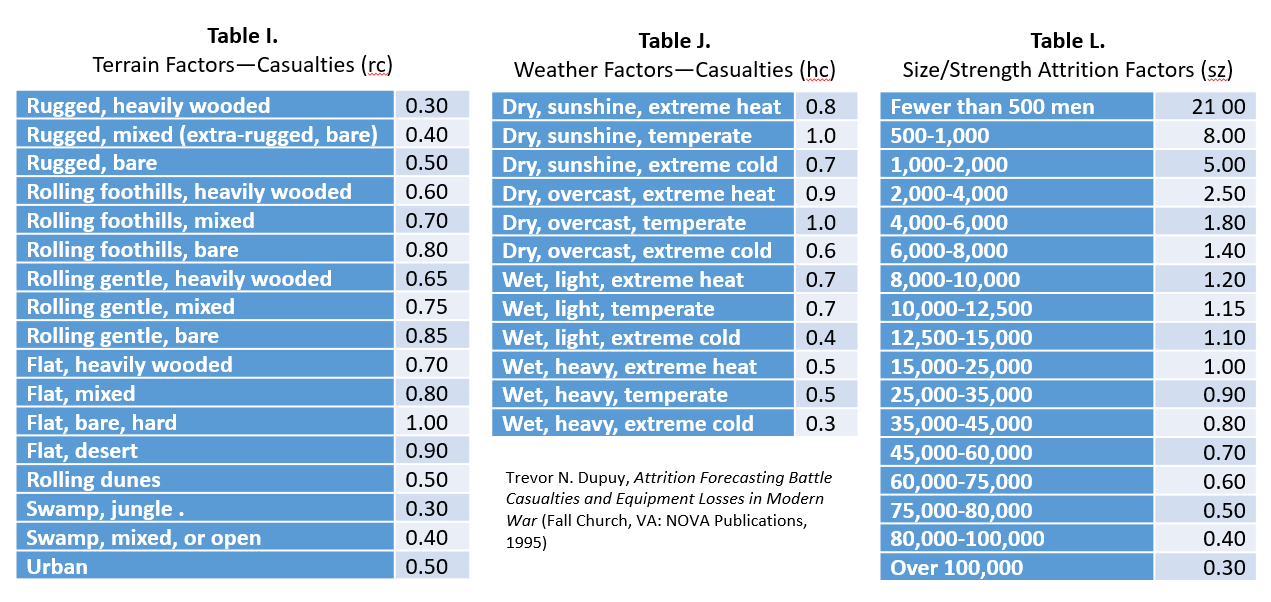

If all of these things are taken into consideration, then it is possible to assess combat intensity fairly consistently. The formula I use is as follows:

CI = CR / (sz’ x rc x hc)

When: CI = Combat Intensity Measure

CR = Casualty rate in percent per day

sz’ = Square root of sz, a factor reflecting the effect of size upon casualty rates, derived from historical experience

rc = The effect of terrain on casualty rates, derived from historical experience

hc = The effect of weather on casualty rates, derived from historical experience

I then (somewhat arbitrarily) identify seven levels of intensity:

0.00 to 0.49 Very low intensity (1)

0.50 to 0.99 Low intensity (56)

1.00 to 1.99 Normal intensity (213)

2.00 to 2.99 High intensity (101)

3.00 to 3.99 Very high intensity (30)

4.00 to 5.00 Extremely high intensity (17)

Over 5.00 Catastrophic outcome (20)

The numbers in parentheses show the distribution of intensity on each side in 219 battles in DMSi’s QJM data base. The catastrophic battles include: the Russians in the Battles of Tannenberg and Gorlice Tarnow on the Eastern Front in World War I; the Russians on the first day of the Battle of Kursk in July 1943; a British defeat in Malaya in December, 1941; and 16 Japanese defeats on Okinawa. Each of these catastrophic instances, quantitatively identified, is consistent with a qualitative assessment of the outcome.

[UPDATE]

As Clinton Reilly pointed out in the comments, this works better when the equation variables are provided. These are from Trevor N. Dupuy, Attrition Forecasting Battle Casualties and Equipment Losses in Modern War (Fall Church, VA: NOVA Publications, 1995), pp. 146, 147, 149.

Human Factors In Warfare: Surprise

Trevor Dupuy considered surprise to be one of the most important human factors on the battlefield.

A military force that is surprised is severely disrupted, and its fighting capability is severely degraded. Surprise is usually achieved by the side that has the initiative, and that is attacking. However, it can be achieved by a defending force. The most common example of defensive surprise is the ambush.

Perhaps the best example of surprise achieved by a defender was that which Hannibal gained over the Romans at the Battle of Cannae, 216 BC, in which the Romans were surprised by the unexpected defensive maneuver of the Carthaginians. This permitted the outnumbered force, aided by the multiplying effect of surprise, to achieve a double envelopment of their numerically stronger force.

It has been hypothesized, and the hypothesis rather conclusively substantiated, that surprise can be quantified in terms of the enhanced mobility (quantifiable) which surprise provides to the surprising force, by the reduced vulnerability (quantifiable) of the surpriser, and the increased vulnerability (quantifiable) of the side that is surprised.

I have written in detail previously about Dupuy’s treatment of surprise. He cited it as one of his timeless verities of combat. As one of the most powerful force multipliers available in battle, he calculated that achieving complete surprise could more than double the combat power of a force.

The U.S. Army’s Stryker Conundrum

As part of an initiative to modernize the U.S. Army in the late 1990s, then-Chief of Staff General Eric Shinseki articulated a need for combat units that were more mobile and rapidly deployable than the existing heavy armor brigades. This was the genesis of the Army’s medium-weight Stryker combat vehicle and the Stryker Brigade Combat Teams (SBCTs).

Since the Stryker’s introduction in 2002, SBCTs have participated successfully in U.S. expeditionary operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, validating for many the usefulness of Shinseki’s original medium-weight armor concept. However, changes in the strategic landscape and advances in technology and operational doctrine by potential adversaries are calling the medium armor concept back into question.

Medium armor faces the same conundrum that currently confronts the U.S. Army in general: should it optimize to conduct wide area security operations (which is the most likely type of future conflict) or combined arms maneuver (the most dangerous potential future conflict), or should it continue to hedge against strategic uncertainty by fielding a balanced, general purpose force which does a tolerable job of both, as it does now?

The Problem

In the current edition of Military Review, U.S. Army Captain Matthew D. Allgeyer presents an interesting critique of the Army’s existing medium-weight armor concept. He asserts that it is “is suffering from a lack of direction and focus…” Several improvements for the Stryker have been proposed based on perceptions of evolving Russian military capabilities, namely “a modern heavy-force threat supported by aviation assets.” The problem, according to Allgeyer, is that

The SBCT community wants all the positive aspects of a light force: lower cost, a small tooth-to-tail ratio, greater operational-level speed, etc. But, it also wants the ability to confront a heavy-armored force on its own terms without having to adopt the cost, support, and deployment time required by an armored force. Since these two ideas are mutuality exclusive, we have been forced to adopt a piecemeal response to shortcomings identified during training and training center rotations.

Even if the currently proposed improvements are adopted however, Allgeyer argues that updated Strykers would only provide the U.S. with a medium weight armor capability analogous to the 1960’s era Soviet motor-rifle regiment, a doctrinal step backward.

Allgeyer identifies the SBCT’s biggest weaknesses as a lack of firepower capable of successfully engaging enemy heavy armor and the absence of an organic air defense capability. Neither of these is a problem in wide area security missions such as peacekeeping or counterinsurgency, where deployability and mobility are priority considerations. However, both shortcomings are critical disadvantages in combined arms maneuver scenarios, particularly against Russian or Russian-equipped opposing forces.

Potential Solutions

These observations are not new. A 2001 TDI study of the historical effectiveness of lighter-weight armor pointed out its vulnerability to heavy armored forces, but also its utility in stability and contingency operations. The Russians long ago addressed these issues with their Bronetransporter (BTR)-equipped motor-rifle regiments by adding organic tank battalions to them, incorporating air defense platoons in each battalion, and upgunning the BTRs with 30mm cannons and anti-tank guided missiles (ATGMs).

The U.S. Army has similar solutions available. It has already sought to add 30mm cannons and TOW-2 ATGMs to the Styker. The Mobile Protected Firepower program that will provide a company of light-weight armored vehicles with high-caliber cannons to each infantry brigade combat team could easily be expanded to add a company or battalion of such vehicles to the SBCT. No proposals exist for improving air defense capabilities, but this too could be addressed.

Allgeyer agrees with the need for these improvements, but he is dissatisfied with the Army “simply reinventing on its own the wheel Russia made a long time ago.” His proposed “solution is a radical restructuring of thought around the Stryker concept.” He advocates ditching the term “Stryker” in favor of the more generic “medium armor” to encourage doctrinal thinking about the concept instead of the platform. Medium armor advocates should accept the need for a combined arms solution to engaging adversary heavy forces and incorporate more joint training into their mission-essential task lists. The Army should also do a better job of analyzing foreign medium armor platforms and doctrine to see what may be appropriate for U.S. adoption.

Allgeyer’s proposals are certainly worthy, but they may not add up to the radical restructuring he seeks. Even if adopted, they are not likely to change the fundamental characteristics of medium armor that make it more suitable to the wide area security mission than to combined arms maneuver. Optimizing it for one mission will invariably make it less useful for the other. Whether or not this is a wise choice is also the same question the Army must ponder with regard to its overall strategic mission.

Human Factors In Warfare: Defensive Posture

Like dispersion on the battlefield, Trevor Dupuy believed that fighting on the defensive derived from the effects of the human element in combat.

When men believe that their chances of survival in a combat situation become less than some value (which is probably quantifiable, and is unquestionably related to a strength ratio or a power ratio), they cannot and will not advance. They take cover so as to obtain some protection, and by so doing they redress the strength or power imbalance. A force with strength y (a strength less than opponent’s strength x) has its strength multiplied by the effect of defensive posture (let’s give it the symbol p) to a greater power value, so that power py approaches, equals, or exceeds x, the unenhanced power value of the force with the greater strength x. It was because of this that [Carl von] Clausewitz–who considered that battle outcome was the result of a mathematical equation[1]–wrote that “defense is a stronger form of fighting than attack.”[2] There is no question that he considered that defensive posture was a combat multiplier in this equation. It is obvious that the phenomenon of the strengthening effect of defensive posture is a combination of physical and human factors.

Dupuy elaborated on his understanding of Clausewitz’s comparison of the impact of the defensive and offensive posture in combat in his book Understanding War.

The statement [that the defensive is the stronger form of combat] implies a comparison of relative strength. It is essentially scalar and thus ultimately quantitative. Clausewitz did not attempt to define the scale of his comparison. However, by following his conceptual approach it is possible to establish quantities for this comparison. Depending upon the extent to which the defender has had the time and capability to prepare for defensive combat, and depending also upon such considerations as the nature of the terrain which he is able to utilize for defense, my research tells me that the comparative strength of defense to offense can range from a factor with a minimum value of about 1.3 to maximum value of more than 3.0.[3]

NOTES

[1] Dupuy believed Clausewitz articulated a fundamental law for combat theory, which Dupuy termed the “Law of Numbers.” One should bear in mind this concept of a theory of combat is something different than a fundamental law of war or warfare. Dupuy’s interpretation of Clausewitz’s work can be found in Understanding War: History and Theory of Combat (New York: Paragon House, 1987), 21-30.

[2] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, translation by Colonel James John Graham (London: N. Trübner, 1873), Book One, Chapter One, Section 17

[3] Dupuy, Understanding War, 26.

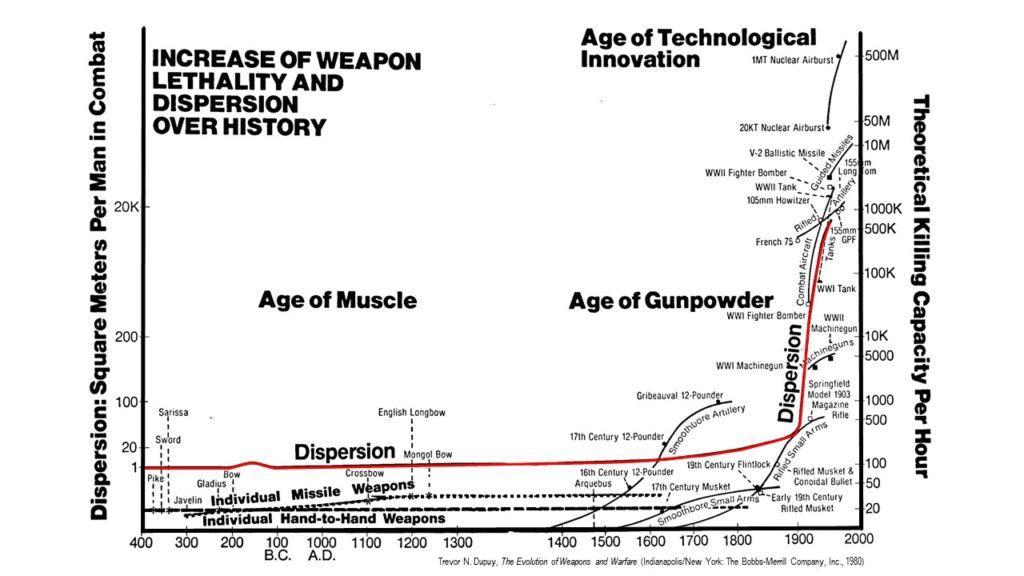

Human Factors In Warfare: Dispersion

As I have written about before, the foundation of Trevor Dupuy’s theories on combat were based on an initial study in 1964 of the relationship between weapon lethality, casualty rates, and dispersion on the battlefield. The historical trend toward greater dispersion was a response to continual increases in the lethality of weapons.

While this relationship might appear primarily technological in nature, Dupuy considered it the result of the human factor of fear on the battlefield. He put it in more human terms in a symposium paper from 1989:

There is one basic reason for the dispersal of troops on modern battlefields: to mitigate the lethal effects of firepower upon troops. As Lewis Richardson wrote in The Statistics of Deadly Quarrels, there is a limit to the amount of punishment human beings can sustain. Dispersion was resorted to as a tactical response to firepower mostly because—as weapons became more lethal in the 17th Century—soldiers were already beginning to disperse without official sanction. This was because they sensed that on the bloody battlefields of that century they were approaching the limit of the punishment men can stand.

More On The U.S. Army’s ‘Identity Crisis’

The new edition of the U.S. Army War College’s quarterly journal Parameters contains additional commentary on the question of whether the Army should be optimizing to wage combined arms maneuver warfare or wide-area security/Security Force Assistance.

The new edition of the U.S. Army War College’s quarterly journal Parameters contains additional commentary on the question of whether the Army should be optimizing to wage combined arms maneuver warfare or wide-area security/Security Force Assistance.

Conrad Crane, the chief of historical services at the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center offers some comments and criticism of an article by Gates Brown, “The Army’s Identity Crisis” in the Winter 2016–17 issue of Parameters. Brown then responds to Crane’s comments.

Attrition In Future Land Combat

Last autumn, U.S. Army Chief of Staff General Mark Milley asserted that “we are on the cusp of a fundamental change in the character of warfare, and specifically ground warfare. It will be highly lethal, very highly lethal, unlike anything our Army has experienced, at least since World War II.” He made these comments while describing the Army’s evolving Multi-Domain Battle concept for waging future combat against peer or near-peer adversaries.

How lethal will combat on future battlefields be? Forecasting the future is, of course, an undertaking fraught with uncertainties. Milley’s comments undoubtedly reflect the Army’s best guesses about the likely impact of new weapons systems of greater lethality and accuracy, as well as improved capabilities for acquiring targets. Many observers have been closely watching the use of such weapons on the battlefield in the Ukraine. The spectacular success of the Zelenopillya rocket strike in 2014 was a convincing display of the lethality of long-range precision strike capabilities.

It is possible that ground combat attrition in the future between peer or near-peer combatants may be comparable to the U.S. experience in World War II (although there were considerable differences between the experiences of the various belligerents). Combat losses could be heavier. It certainly seems likely that they would be higher than those experienced by U.S. forces in recent counterinsurgency operations.

Unfortunately, the U.S. Defense Department has demonstrated a tenuous understanding of the phenomenon of combat attrition. Despite wildly inaccurate estimates for combat losses in the 1991 Gulf War, only modest effort has been made since then to improve understanding of the relationship between combat and casualties. The U.S. Army currently does not have either an approved tool or a formal methodology for casualty estimation.

Historical Trends in Combat Attrition

Trevor Dupuy did a great deal of historical research on attrition in combat. He found several trends that had strong enough empirical backing that he deemed them to be verities. He detailed his conclusions in Understanding War: History and Theory of Combat (1987) and Attrition: Forecasting Battle Casualties and Equipment Losses in Modern War (1995).

Dupuy documented a clear relationship over time between increasing weapon lethality, greater battlefield dispersion, and declining casualty rates in conventional combat. Even as weapons became more lethal, greater dispersal in frontage and depth among ground forces led daily personnel loss rates in battle to decrease.

The average daily battle casualty rate in combat has been declining since 1600 as a consequence. Since battlefield weapons continue to increase in lethality and troops continue to disperse in response, it seems logical to presume the trend in loss rates continues to decline, although this may not necessarily be the case. There were two instances in the 19th century where daily battle casualty rates increased—during the Napoleonic Wars and the American Civil War—before declining again. Dupuy noted that combat casualty rates in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War remained roughly the same as those in World War II (1939-45), almost thirty years earlier. Further research is needed to determine if average daily personnel loss rates have indeed continued to decrease into the 21st century.

The average daily battle casualty rate in combat has been declining since 1600 as a consequence. Since battlefield weapons continue to increase in lethality and troops continue to disperse in response, it seems logical to presume the trend in loss rates continues to decline, although this may not necessarily be the case. There were two instances in the 19th century where daily battle casualty rates increased—during the Napoleonic Wars and the American Civil War—before declining again. Dupuy noted that combat casualty rates in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War remained roughly the same as those in World War II (1939-45), almost thirty years earlier. Further research is needed to determine if average daily personnel loss rates have indeed continued to decrease into the 21st century.

Dupuy also discovered that, as with battle outcomes, casualty rates are influenced by the circumstantial variables of combat. Posture, weather, terrain, season, time of day, surprise, fatigue, level of fortification, and “all out” efforts affect loss rates. (The combat loss rates of armored vehicles, artillery, and other other weapons systems are directly related to personnel loss rates, and are affected by many of the same factors.) Consequently, yet counterintuitively, he could find no direct relationship between numerical force ratios and combat casualty rates. Combat power ratios which take into account the circumstances of combat do affect casualty rates; forces with greater combat power inflict higher rates of casualties than less powerful forces do.

Dupuy also discovered that, as with battle outcomes, casualty rates are influenced by the circumstantial variables of combat. Posture, weather, terrain, season, time of day, surprise, fatigue, level of fortification, and “all out” efforts affect loss rates. (The combat loss rates of armored vehicles, artillery, and other other weapons systems are directly related to personnel loss rates, and are affected by many of the same factors.) Consequently, yet counterintuitively, he could find no direct relationship between numerical force ratios and combat casualty rates. Combat power ratios which take into account the circumstances of combat do affect casualty rates; forces with greater combat power inflict higher rates of casualties than less powerful forces do.

Winning forces suffer lower rates of combat losses than losing forces do, whether attacking or defending. (It should be noted that there is a difference between combat loss rates and numbers of losses. Depending on the circumstances, Dupuy found that the numerical losses of the winning and losing forces may often be similar, even if the winner’s casualty rate is lower.)

Dupuy’s research confirmed the fact that the combat loss rates of smaller forces is higher than that of larger forces. This is in part due to the fact that smaller forces have a larger proportion of their troops exposed to enemy weapons; combat casualties tend to concentrated in the forward-deployed combat and combat support elements. Dupuy also surmised that Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz’s concept of friction plays a role in this. The complexity of interactions between increasing numbers of troops and weapons simply diminishes the lethal effects of weapons systems on real world battlefields.

Somewhat unsurprisingly, higher quality forces (that better manage the ambient effects of friction in combat) inflict casualties at higher rates than those with less effectiveness. This can be seen clearly in the disparities in casualties between German and Soviet forces during World War II, Israeli and Arab combatants in 1973, and U.S. and coalition forces and the Iraqis in 1991 and 2003.

Combat Loss Rates on Future Battlefields

What do Dupuy’s combat attrition verities imply about casualties in future battles? As a baseline, he found that the average daily combat casualty rate in Western Europe during World War II for divisional-level engagements was 1-2% for winning forces and 2-3% for losing ones. For a divisional slice of 15,000 personnel, this meant daily combat losses of 150-450 troops, concentrated in the maneuver battalions (The ratio of wounded to killed in modern combat has been found to be consistently about 4:1. 20% are killed in action; the other 80% include mortally wounded/wounded in action, missing, and captured).

It seems reasonable to conclude that future battlefields will be less densely occupied. Brigades, battalions, and companies will be fighting in spaces formerly filled with armies, corps, and divisions. Fewer troops mean fewer overall casualties, but the daily casualty rates of individual smaller units may well exceed those of WWII divisions. Smaller forces experience significant variation in daily casualties, but Dupuy established average daily rates for them as shown below.

For example, based on Dupuy’s methodology, the average daily loss rate unmodified by combat variables for brigade combat teams would be 1.8% per day, battalions would be 8% per day, and companies 21% per day. For a brigade of 4,500, that would result in 81 battle casualties per day, a battalion of 800 would suffer 64 casualties, and a company of 120 would lose 27 troops. These rates would then be modified by the circumstances of each particular engagement.

Several factors could push daily casualty rates down. Milley envisions that U.S. units engaged in an anti-access/area denial environment will be constantly moving. A low density, highly mobile battlefield with fluid lines would be expected to reduce casualty rates for all sides. High mobility might also limit opportunities for infantry assaults and close quarters combat. The high operational tempo will be exhausting, according to Milley. This could also lower loss rates, as the casualty inflicting capabilities of combat units decline with each successive day in battle.

It is not immediately clear how cyberwarfare and information operations might influence casualty rates. One combat variable they might directly impact would be surprise. Dupuy identified surprise as one of the most potent combat power multipliers. A surprised force suffers a higher casualty rate and surprisers enjoy lower loss rates. Russian combat doctrine emphasizes using cyber and information operations to achieve it and forces with degraded situational awareness are highly susceptible to it. As Zelenopillya demonstrated, surprise attacks with modern weapons can be devastating.

Some factors could push combat loss rates up. Long-range precision weapons could expose greater numbers of troops to enemy fires, which would drive casualties up among combat support and combat service support elements. Casualty rates historically drop during night time hours, although modern night-vision technology and persistent drone reconnaissance might will likely enable continuous night and day battle, which could result in higher losses.

Drawing solid conclusions is difficult but the question of future battlefield attrition is far too important not to be studied with greater urgency. Current policy debates over whether or not the draft should be reinstated and the proper size and distribution of manpower in active and reserve components of the Army hinge on getting this right. The trend away from mass on the battlefield means that there may not be a large margin of error should future combat forces suffer higher combat casualties than expected.

On Domains And Doctrine

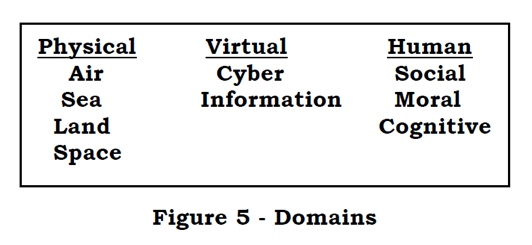

There is a lot of smart writing being published over at The Strategy Bridge. If you don’t follow it, you should. Among the recent offerings is a very good piece by Erik Heftye, a retired Air Force officer and senior military analyst in the U.S. Army’s Mission Command Battle Laboratory at Fort Leavenworth. His article “Multi-Domain Confusion: All Domains Are Not Created Equal,” takes a look at an au courant topic central to the new concept of Multi-Domain Battle (MDB).

Defense grognards have been grumbling that MDB is just a new term for an old concept. This is true, insofar as it goes. I am not sure this is in dispute. After all, the subtitle of the U.S. Army/U.S. Marine Corps MDB white paper is “Combined Arms For The 21st Century.” However, such comments do raise the issue of whether new terms for old concepts are serving to clarify or cloud current understanding.

This is Heftye’s concern regarding the use of the term domain: “An ambiguous categorization of separate operating domains in warfare could actually pose an intractable conceptual threat to an integrated joint force, which is ironically the stated purpose of multi-domain battle.” Noting the vagueness of the concept, Heftye traces how the term entered into U.S. military doctrine in the 1990s and evolved into the current four physical (land, sea, air, and space) and one virtual (cyberspace) warfighting realms. He then discusses the etymology of the word and how its meanings imply that all of the domains are equivalent in nature and importance. While this makes sense for air, sea, and land, the physical aspects of those domains do not translate to space or cyberspace. He argues that treating them all analogously will inevitably lead to conceptual confusion.

Heftye recommends a solution: “In order to minimize the problem of domain equivalence, a revised construct should distinguish different types of domains in relation to relevant and advantageous warfighting effects. Focusing on effects rather than domains would allow for the elimination of unnecessary bureaucratic seams, gaps, and turf wars.” He offers up a simplified variation of the domain construct that had been published in the superseded 2005 edition of the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s Capstone Concept for Joint Operations, which defined a domain as “any potential operating ‘space’ through which the target system can be influenced—not only the domains of land, sea, air, and space, but also the virtual (information and cyber) and human (cognitive, moral, and social) domains.”

This version not only simplifies by cutting the five existing categories to three, but it also groups like with like. “Land, sea, air, and space are physical domains involving material reality. Cyberspace and information, as well as the electromagnetic spectrum are virtual domains involving sensing and perception. The construct also included a human category involving value judgements.” Heftye acknowledges that looking at domains in terms of effects runs contrary to then-Joint Forces Commander General (and current Defense Secretary) James Mattis’s ban on the use of the Effects Based Operations (EBO) concept by the U.S. military 2008. He also points out that the concept of domains will not be going away anytime soon, either.

Of course, conceptual confusion is not a unique problem in U.S. military doctrine argues Steve Leonard in “Broken and Unreadable: Our Unbearable Aversion to Doctrine,” over at the Modern War Institute at West Point (which is also publishing great material these days). Leonard (aka Doctrine Man!!), a former U.S. Army senior strategist, ruminates about dissatisfaction and discontent with the American “rules of the game.” He offers up a personal anecdote about a popular military staff pastime: defining doctrinal terms.

We also tend to over-define our terminology. Words in common usage since the days of Noah Webster can find new life—and new meaning—in Army doctrine. Several years ago, I endured an hours-long argument among a group of doctrine writers trying to define the term “asymmetric.” The suggestion—after three full hours of debate—that the group consult a dictionary was not well-received.

I have no doubt Erik Heftye feels your pain, Doctrine Man.

Sketching Out Multi-Domain Battle Operational Doctrine

Small Wars Journal has published an insightful essay by U.S. Army Major Amos Fox, “Multi-Domain Battle: A Perspective on the Salient Features of an Emerging Operational Doctrine.” Fox is a recent graduate of Army’s School of Advanced Military Studies (SAMS) and author of several excellent pieces assessing Russian military doctrine and its application in the Ukraine.

Drawing upon an array of sources, including recent Russian military operations, preliminary conceptualizations of MDB, Carl von Clausewitz, J.F.C Fuller, and maneuver warfare theory, Fox takes a crack at shaping the parameters of a doctrine for Multi-Domain Battle (MDB) operations on land. He begins by summarizing how MDB will connect operations to strategy.

Current proponents suggest that [MDB] will occur against peer competitors in contested environments, providing the US Army and its joint partners with a much thinner margin of victory than in the recent past. As such, US forces should look to create zones of proximal dominance to enable the active pursuit of objectives and end states, and that dislocation is the key to defeating an adversary capable of multi-domain operations.

The essence of MDB will be a constant struggle for battlespace dominance, which will be “fleeting, fragile, and prone to shock or surprise.” Achieving temporary dominance only establishes the pre-conditions necessary for closing with and destroying enemy forces, however.

Fox suggests envisioning the cross-domain, combined arms, and individual arms of ground forces (i.e. direct fire weapons, indirect fire weapons, cyber, electronic, information, reconnaissance, et cetera) as “zones of proximal dominance” or “as an orb of power which radiates from a central position.” Long-range weapons perform a protective function and form the outer layers of the zone, while shorter-range weapons constitute the fighting functions.

[O]ne must understand that in multi-domain battle they must first strip away, or dislocate, the protective layers of an enemy’s force in order to destroy its strength, or its inner core. In the cross-domain environment, an enemy’s outer core is its cross-domain and joint capabilities. Therefore, the more of the enemy’s outer can be cleaved away or neutralized, the more success friendly forces will have in defeating the enemy’s main fighting force. Dislocating the outer layers and destroying the inner core will, in essence, defeats the cross-domain enemy.

Dislocation is a concept Fox adopts from maneuver warfare theory as “a critical component of defeating an enemy with cross-domain capabilities because it denies the enemy access to its tools, renders those tools irrelevant, or forces the enemy into environments in which those tools are ill-disposed.”

Fox’s perspective is well informed and logical, but exploration of the implications of MDB are in the earliest stages. The essay is a fascinating and highly-recommended read.