In the recently issued 2018 National Defense Strategy, the United States acknowledged that “long-term strategic competitions with China and Russia are the principal priorities for the Department [of Defense], and require both increased and sustained investment, because of the magnitude of the threats they pose to U.S. security and prosperity today, and the potential for those threats to increase in the future.”

The strategy statement lists technologies that will be focused upon:

The drive to develop new technologies is relentless, expanding to more actors with lower barriers of entry, and moving at accelerating speed. New technologies include advanced computing, “big data” analytics, artificial intelligence, autonomy, robotics, directed energy, hypersonics, and biotechnology— the very technologies that ensure we will be able to fight and win the wars of the future… The Department will invest broadly in military application of autonomy, artificial intelligence, and machine learning, including rapid application of commercial breakthroughs, to gain competitive military advantages.” (emphasis added).

Autonomy, robotics, artificial intelligence and machine learning…these are all related to the concept of “drone swarms.” TDI has reported previously on the idea of drone swarms on land. There is indeed promise in many domains of warfare for such technology. In testimony to the Senate Armed Services Committee on the future of warfare, Mr Bryan Clark of the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments argued that “America should apply new technologies to four main areas of warfare: undersea, strike, air and electromagnetic.”

Drones have certainly transformed the way that the U.S. wages war from the air. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) innovated, deployed and fired weapons from drones first against the Taliban in Afghanistan, less than one month after the 9/11 attacks against the U.S. homeland. Most drones today are airborne, partly because it is generally easier to navigate in the air than it is on the land, due to fewer obstacles and more uniform and predictable terrain. The same is largely true of the oceans, at least the blue water parts.

Aerial Drones and Artificial Intelligence

It is important to note that the drones in active use today by the U.S. military are actually remotely piloted Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). With the ability to fire missiles since 2001, one could argue that these crossed the threshold into Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles (UCAVs), but nonetheless, they have a pilot—typically a U.S. Air Force (USAF) member, who would very much like to be flying an F-16, rather than sitting in a shipping container in the desert somewhere safe, piloting a UAV in a distant theater of war.

Given these morale challenges, work on autonomy is clearly underway. Let’s look at a forecast from The Economist, which follows the development of artificial intelligence (AI) in both the commercial and military realms.

A distinction needs to be made between “narrow” AI, which allows a machine to carry out a specific task much better than a human could, and “general” AI, which has far broader applications. Narrow AI is already in wide use for civilian tasks such as search and translation, spam filters, autonomous vehicles, high-frequency stock trading and chess-playing computers… General AI may still be at least 20 years off. A general AI machine should be able to carry out almost any intellectual task that a human is capable of.” (emphasis added)

Thus, it is reasonable to assume that the U.S. military (or others) will not field a fully automated drone, capable of prosecuting a battle without human assistance, until roughly 2038. This means that in the meantime, a human will be somewhere “in” or “on” the loop, making at least some of the decisions, especially those involving deadly force.

The CIA’s initial generation of UAVs was armed in an ad-hoc fashion; further innovation was spurred by the drive to seek out and destroy the 9/11 perpetrators. These early vehicles were designed for intelligence, reconnaissance, and surveillance (ISR) missions. In this role, drones have some big advantages over manned aircraft, including the ability to loiter for long periods. They are not quick, not very maneuverable, and as such are suited to operations in permissive airspace.

The development of UCAVs has allowed their integration into strike (air-to-ground) and air superiority (air-to-air) missions in contested airspace. UCAV strike missions could target and destroy land and sea nodes in command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (C4ISR) networks in an attempt to establish “information dominance.” They might also be targeted against assets like surface to air missiles and radars, part of an adversary anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capability.

Given the sophistication of Russian and Chinese A2/AD networks and air forces, some focus should be placed upon developing more capable and advanced drones required to defeat these challenges. One example comes from Kratos, a drone maker, and reported on in Popular Science.

The Mako drone pictured above has much higher performance than some other visions of future drone swarms, which look more like paper airplanes. Given their size and numbers, they might be difficult to shoot down entirely, and this might be able to operate reasonably well within contested airspace. But, they’re not well suited for air-to-air combat, as they will not have the weapons or the speed necessary to engage with current manned aircraft in use with potential enemy air forces. Left unchecked, an adversary’s current fighters and bombers could easily avoid these types of drones and prosecute their own attacks on vital systems, installations and facilities.

The real utility of drones may lie in the unique tactic for which they are suited, swarming. More on that in my next post.

During this phase, planners are advised to account for “factors that are difficult to gauge, such as impact of past engagements, quality of leaders, morale, maintenance of equipment, and time in position. Levels of electronic warfare support, fire support, close air support, civilian support, and many other factors also affect arraying forces.” FM 6-0 offers no detail as to how these factors should be measured or applied, however.

During this phase, planners are advised to account for “factors that are difficult to gauge, such as impact of past engagements, quality of leaders, morale, maintenance of equipment, and time in position. Levels of electronic warfare support, fire support, close air support, civilian support, and many other factors also affect arraying forces.” FM 6-0 offers no detail as to how these factors should be measured or applied, however.

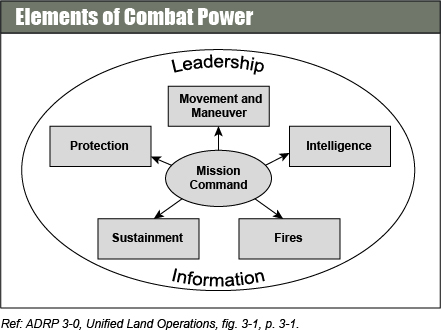

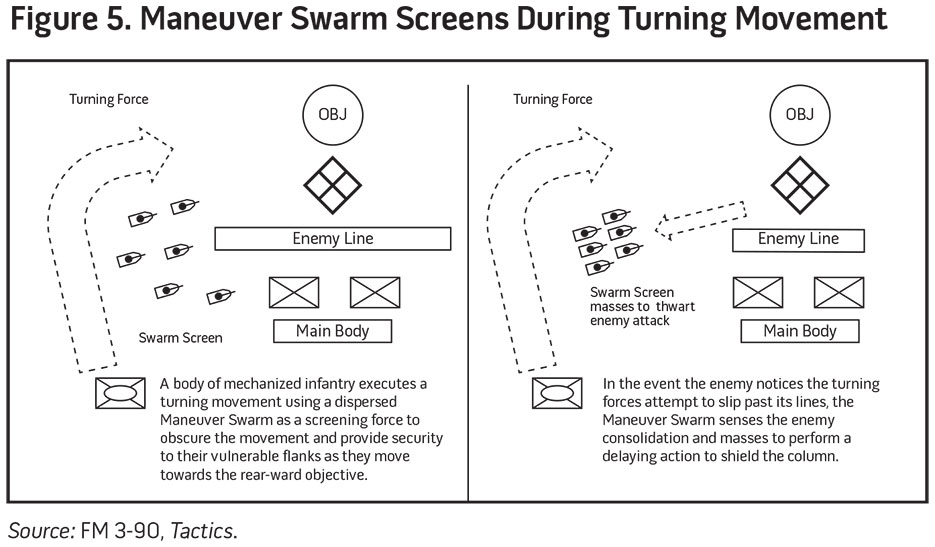

For a while now, military pundits have speculated about the role robotic drones and swarm tactics will play in future warfare. U.S. Army Captain Jules Hurst recently took a first crack at adapting drones and swarms into existing doctrine in

For a while now, military pundits have speculated about the role robotic drones and swarm tactics will play in future warfare. U.S. Army Captain Jules Hurst recently took a first crack at adapting drones and swarms into existing doctrine in