[This post is based on “Iranian Casualties in the Iran-Iraq War: A Reappraisal,” by H. W. Beuttel, originally published in the December 1997 edition of the International TNDM Newsletter.]

Posts in this series:

Iranian Casualties in the Iran-Iraq War: A Reappraisal

Iranian Missing In Action From The Iran-Iraq War

Iranian Prisoners of War From The Iran-Iraq War

The “Missing” Iranian Prisoners of War From The Iran-Iraq War

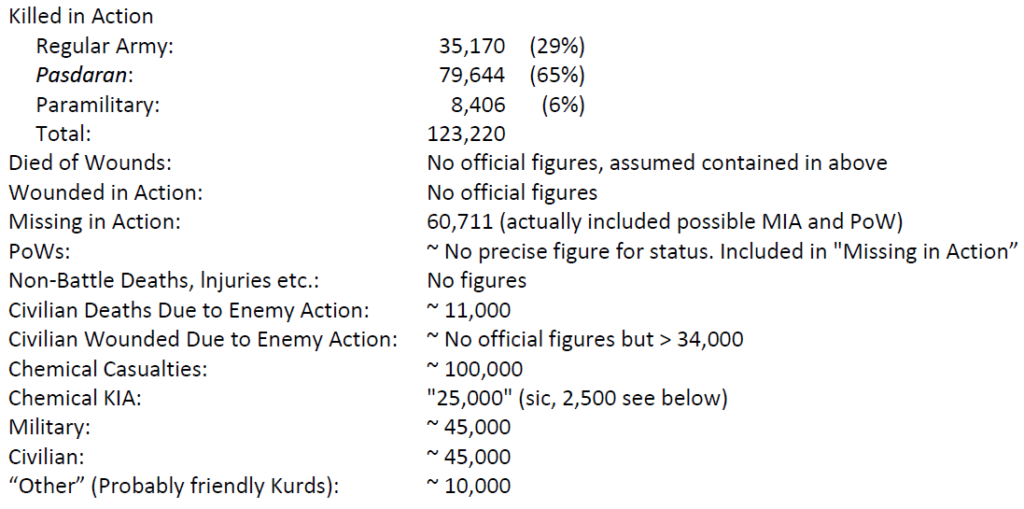

Iranian Killed And Died Of Wounds In The Iran-Iraq War

Iranian Wounded In Action In The Iran-Iraq War

Iranian Chemical Casualties In The Iran-Iraq War

Iranian Civil Casualties In The Iran-Iraq War

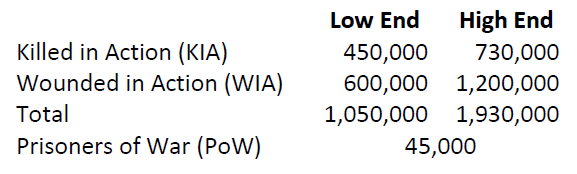

A Summary Estimate Of Iranian Casualties In The Iran-Iraq War

Iranian Missing in Action: Wanted Dead or Alive

By 1995 Iran had conducted seventeen dedicated MIA [missing in action] retrieval operations from wartime battlefields. Approximately 80% of the MIAs are believed to lie in Iraqi territory. In that year Iran proposed a joint Iranian-Iraqi accord to retrieve the missing of both sides.[18] Brigadier General Mir Feisel Baqerzadeh and IRGC Brigadier General Behahim Safaie head the Special Commission for MIA Retrieval. Iran claimed to have recovered or settled some 21,000 cases by early 1995. In that time 2,505 MIAs had been retrieved by joint search operations in Iraq and another 12,638 in Iranian territory, the latter representing 85% of those estimated missing in Iranian held ground. Back calculating these figures indicates total Iranian missing was now regarded as 72,753, up 20% from the original figure of 60,711. By October 1996 the count was 24,000 retrieved.[19] By June of 1997 the number of MIA cases resolved had risen to 33,000 including 6,000 death certificates issued at family request for individuals of whom no trace had ever been found.[20] As of September 1997 the total number of MIA bodies recovered stood at over 37,000 according to Brigadier General Baqerzadeh.[21] “Martyr” (i.e. killed in action) status entitles the family to a $24,000 lump sum death benefit as well as a $280 monthly pension with provision for $56 a month for each dependent child from the Foundation for the Martyrs,[22]

The rate of actual forensic identification of the remains is unknown. One source mentions a positive identification of some 900. The standard practice seems to be determination of the operation in which they were martyred and the provincial origins of units in that engagement. Wartime operations which have yielded large numbers of MIA remains are Beit al-Moqqadas-4, Kheiber, Karbala-4, Karbala-5, Karbala-6, Karbala-8, Karbala-10, Ramazan, Badr, Kheiber, Muslim Ibn-e Aqil, Wal Fajir Preliminary Operation, Wal Fajir-1, Wal Fajir-2, Wal Fajir-6, Wal Fajir-8, Fath-5, and the Iraqi attacks on Majnoon and Shalamech, The retrieval operations are often dangerous and occur in former minefields. As of 1995 eleven IRGC personnel had been killed and fourteen seriously wounded in MIA retrieval operations. Individual military units often recover their own MIAs. In a speech at Gurgan, Ali Mirtaheri, head of the committee in charge of search teams for MIAs of the 27th Huzrat-e Rasul Pasdaran Infantry Division, stated in November 1997 that divisional teams had recovered 1,610 MIA bodies. Forty-two team members from the division have been killed and another eighty maimed in the operations (probably from leftover mines).[23]

Due to the number of cases and the vigorous retrieval operations MIA funerals tend to be mass affairs. Burials in Tehran alone tell the story. In October 1993 208 were buried in Tehran and 360 in other locations. In October 1994 1,000 martyrs were buried in Tehran; in April 1995 another 600 of 3,000 just recovered MIAs and the following month 405 more in Mashad; in October 1995 600 were interred; 750 in October 1996; 1,000 more in January 1997; in July 1997 another 2,000 including 400 from Tehran Province were interred nationwide; in September 1997 200 of 1,233 interred nationwide, including 47 in Qazvin, 34 in Khuzistan, 5 in Shustar and 5 in Sistan-Baluchistan. Of these only 118 were unknowns.[24] Unrecovered Iranian MIAs are carried as active soldiers on their unit personnel rolls with their current status listed simply as “still at the front.” Iran has also recovered Iraqi MIAs, returning up to 400 bodies at a time in a mutual exchange program usually accomplished at the Khosrawi border station in Kermanshah Province.[25] A total of 31,000 Iraqi bodies have been so returned compared to 2,500 Iranian dead returned by Iraq as of January 1997.[26] In January 1997, in conjunction with the Iraqi return of the remains of sixty Iranian MIAs of the Wal Fajir Preliminary Operation, Brigadier General Mir Feisel Baqerzadeh stated that Iran was willing to assume all search responsibilities and associated costs for both Iraqi and Iranian MIAs on Iraqi territory should Iraq not wish to continue recovery operations.[27] In May 1997 Brigadier General Mohammed Balar, spokesman for the Commission for Iranian PoWs, called on international organizations to pressure Iraq to clarify the status of 20,000 Iranian MIAs.[28]

Mr Beuttel, a former U.S. Army intelligence officer, was employed as a military analyst by Boeing Research & Development at the time of original publication. The views and opinions expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of The Boeing Company.

Armies have historically responded to the increasing lethality of weapons by dispersing mass in frontage and depth on the battlefield. Will combat see a new period of adjustment over the next 50 years like the previous half-century, where dispersion continues to shift in direct proportion to increased weapon range and precision, or will there be a significant change in the character of warfare?

Armies have historically responded to the increasing lethality of weapons by dispersing mass in frontage and depth on the battlefield. Will combat see a new period of adjustment over the next 50 years like the previous half-century, where dispersion continues to shift in direct proportion to increased weapon range and precision, or will there be a significant change in the character of warfare?