[The article below is reprinted from the Winter 2010 edition of The International TNDM Newsletter.]

Comparing the RAND Version of the 3:1 Rule to Real-World Data

Christopher A. Lawrence

For this test, The Dupuy Institute took advantage of two of its existing databases for the DuWar suite of databases. The first is the Battles Database (BaDB), which covers 243 battles from 1600 to 1900. The second is the Division-level Engagement Database (DLEDB), which covers 675 division-level engagements from 1904 to 1991.

The first was chosen to provide a historical context for the 3:1 rule of thumb. The second was chosen so as to examine how this rule applies to modern combat data.

We decided that this should be tested to the RAND version of the 3:1 rule as documented by RAND in 1992 and used in JICM [Joint Integrated Contingency Model] (with SFS [Situational Force Scoring]) and other models. This rule, as presented by RAND, states: “[T]he famous ‘3:1 rule,’ according to which the attacker and defender suffer equal fractional loss rates at a 3:1 force ratio if the battle is in mixed terrain and the defender enjoys ‘prepared’ defenses…”

Therefore, we selected out all those engagements from these two databases that ranged from force ratios of 2.5 to 1 to 3.5 to 1 (inclusive). It was then a simple matter to map those to a chart that looked at attackers losses compared to defender losses. In the case of the pre-1904 cases, even with a large database (243 cases), there were only 12 cases of combat in that range, hardly statistically significant. That was because most of the combat was at odds ratios in the range of .50-to-1 to 2.00-to-one.

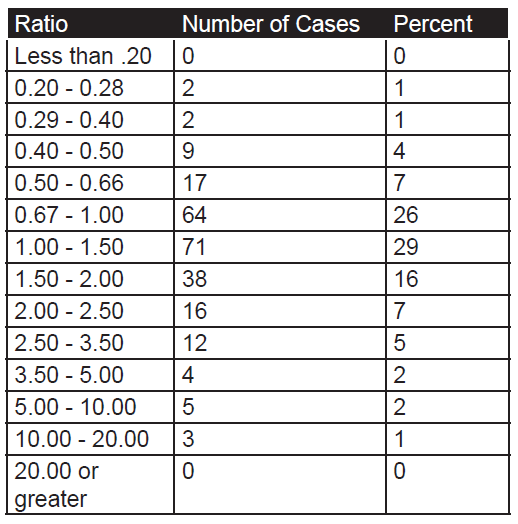

The count of number of engagements by odds in the pre-1904 cases:

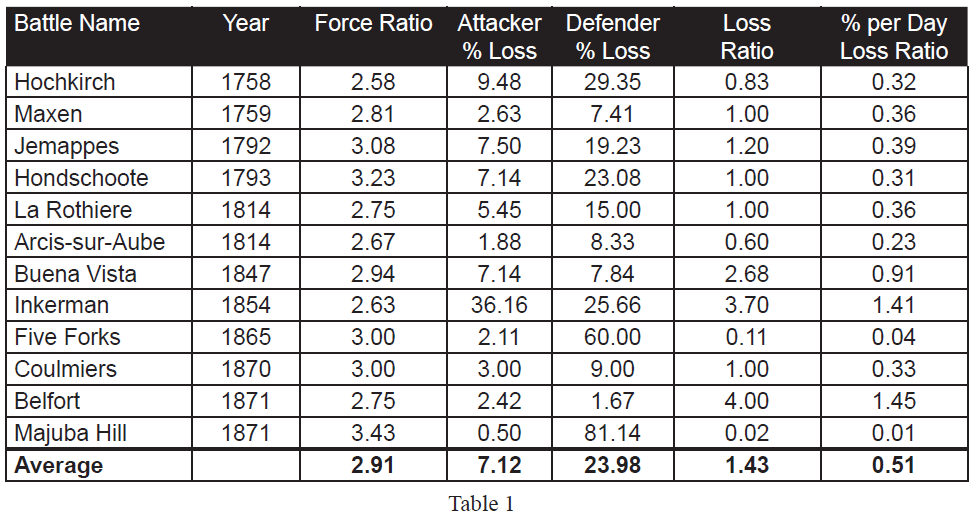

As the database is one of battles, then usually these are only joined at reasonably favorable odds, as shown by the fact that 88 percent of the battles occur between 0.40 and 2.50 to 1 odds. The twelve pre-1904 cases in the range of 2.50 to 3.50 are shown in Table 1.

As the database is one of battles, then usually these are only joined at reasonably favorable odds, as shown by the fact that 88 percent of the battles occur between 0.40 and 2.50 to 1 odds. The twelve pre-1904 cases in the range of 2.50 to 3.50 are shown in Table 1.

If the RAND version of the 3:1 rule was valid, one would expect that the “Percent per Day Loss Ratio” (the last column) would hover around 1.00, as this is the ratio of attacker percent loss rate to the defender percent loss rate. As it is, 9 of the 12 data points are noticeably below 1 (below 0.40 or a 1 to 2.50 exchange rate). This leaves only three cases (25%) with an exchange rate that would support such a “rule.”

If the RAND version of the 3:1 rule was valid, one would expect that the “Percent per Day Loss Ratio” (the last column) would hover around 1.00, as this is the ratio of attacker percent loss rate to the defender percent loss rate. As it is, 9 of the 12 data points are noticeably below 1 (below 0.40 or a 1 to 2.50 exchange rate). This leaves only three cases (25%) with an exchange rate that would support such a “rule.”

If we look at the simple ratio of actual losses (vice percent losses), then the numbers comes much closer to parity, but this is not the RAND interpretation of the 3:1 rule. Six of the twelve numbers “hover” around an even exchange ratio, with six other sets of data being widely off that central point. “Hover” for the rest of this discussion means that the exchange ratio ranges from 0.50-to-1 to 2.00-to 1.

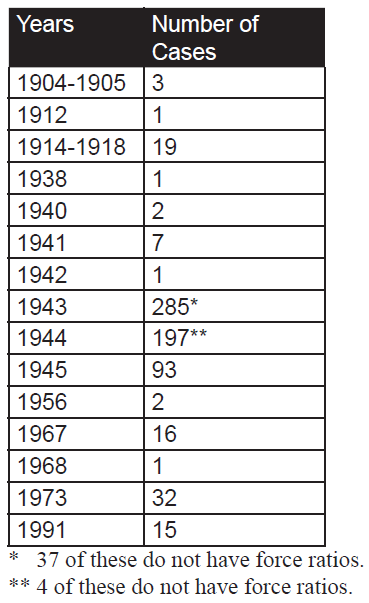

Still, this is early modern linear combat, and is not always representative of modern war. Instead, we will examine 634 cases in the Division-level Database (which consists of 675 cases) where we have worked out the force ratios. While this database covers from 1904 to 1991, most of the cases are from WWII (1939- 1945). Just to compare:

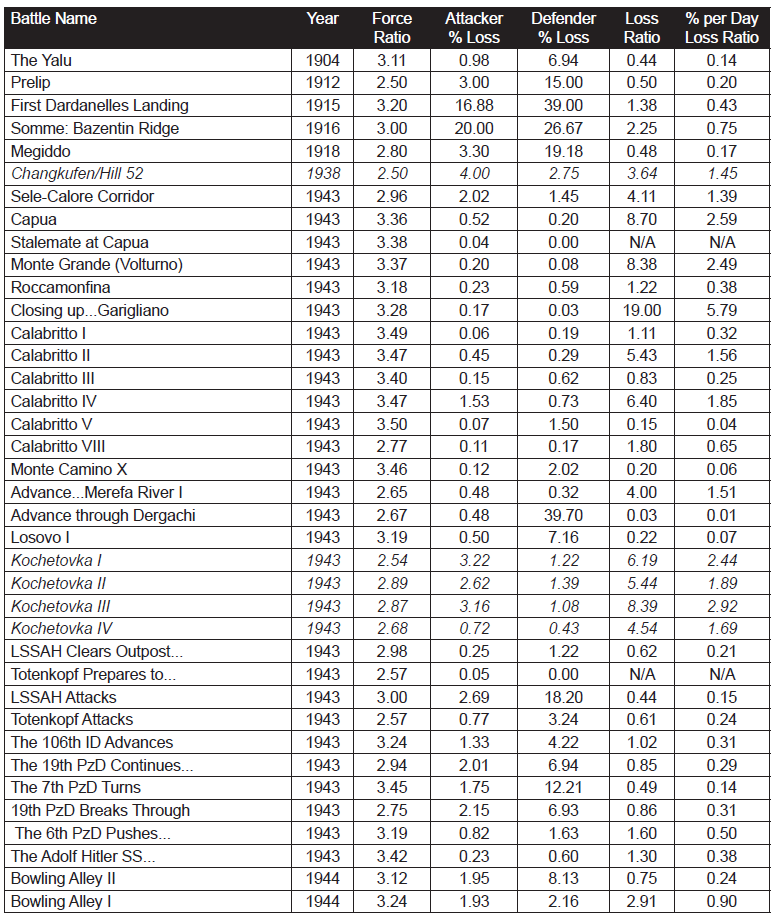

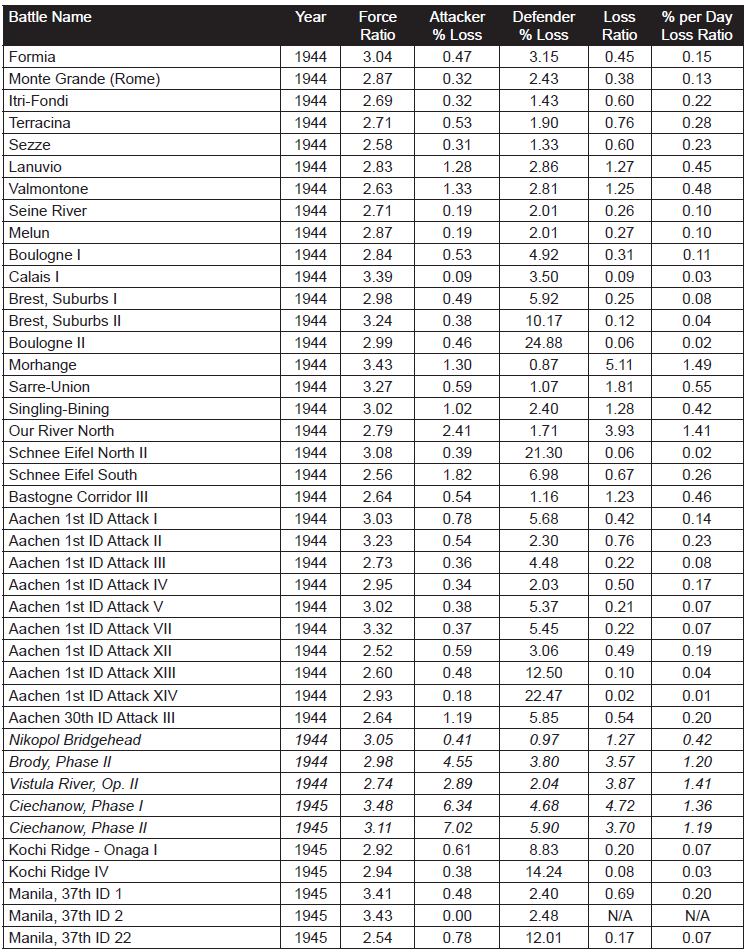

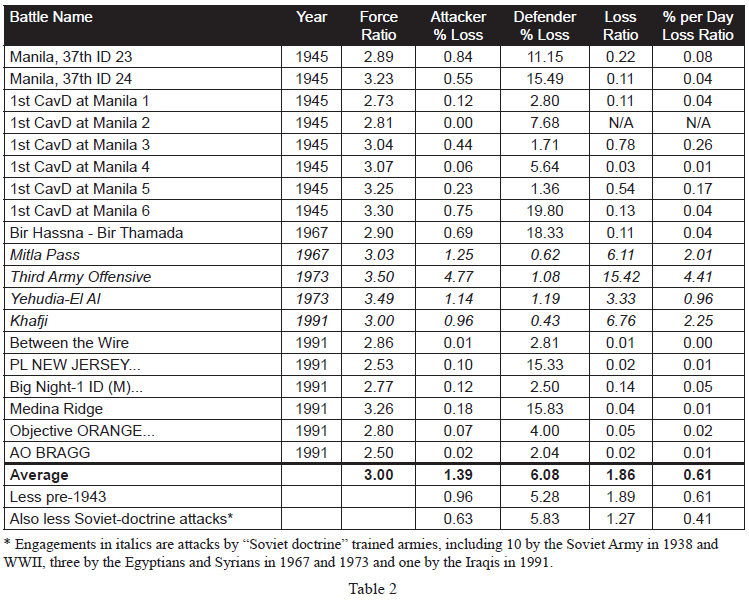

As such, 87% of the cases are from WWII data and 10% of the cases are from post-WWII data. The engagements without force ratios are those that we are still working on as The Dupuy Institute is always expanding the DLEDB as a matter of routine. The specific cases, where the force ratios are between 2.50 and 3.50 to 1 (inclusive) are shown in Table 2:

As such, 87% of the cases are from WWII data and 10% of the cases are from post-WWII data. The engagements without force ratios are those that we are still working on as The Dupuy Institute is always expanding the DLEDB as a matter of routine. The specific cases, where the force ratios are between 2.50 and 3.50 to 1 (inclusive) are shown in Table 2:

This is a total of 98 engagements at force ratios of 2.50 to 3.50 to 1. It is 15 percent of the 634 engagements for which we had force ratios. With this fairly significant representation of the overall population, we are still getting no indication that the 3:1 rule, as RAND postulates it applies to casualties, does indeed fit the data at all. Of the 98 engagements, only 19 of them demonstrate a percent per day loss ratio (casualty exchange ratio) between 0.50-to-1 and 2-to-1. This is only 19 percent of the engagements at roughly 3:1 force ratio. There were 72 percent (71 cases) of those engagements at lower figures (below 0.50-to-1) and only 8 percent (cases) are at a higher exchange ratio. The data clearly was not clustered around the area from 0.50-to- 1 to 2-to-1 range, but was well to the left (lower) of it.

This is a total of 98 engagements at force ratios of 2.50 to 3.50 to 1. It is 15 percent of the 634 engagements for which we had force ratios. With this fairly significant representation of the overall population, we are still getting no indication that the 3:1 rule, as RAND postulates it applies to casualties, does indeed fit the data at all. Of the 98 engagements, only 19 of them demonstrate a percent per day loss ratio (casualty exchange ratio) between 0.50-to-1 and 2-to-1. This is only 19 percent of the engagements at roughly 3:1 force ratio. There were 72 percent (71 cases) of those engagements at lower figures (below 0.50-to-1) and only 8 percent (cases) are at a higher exchange ratio. The data clearly was not clustered around the area from 0.50-to- 1 to 2-to-1 range, but was well to the left (lower) of it.

Looking just at straight exchange ratios, we do get a better fit, with 31 percent (30 cases) of the figure ranging between 0.50 to 1 and 2 to 1. Still, this figure exchange might not be the norm with 45 percent (44 cases) lower and 24 percent (24 cases) higher. By definition, this fit is 1/3rd the losses for the attacker as postulated in the RAND version of the 3:1 rule. This is effectively an order of magnitude difference, and it clearly does not represent the norm or the center case.

The percent per day loss exchange ratio ranges from 0.00 to 5.71. The data tends to be clustered at the lower values, so the high values are very much outliers. The highest percent exchange ratio is 5.71, the second highest is 4.41, the third highest is 2.92. At the other end of the spectrum, there are four cases where no losses were suffered by one side and seven where the exchange ratio was .01 or less. Ignoring the “N/A” (no losses suffered by one side) and the two high “outliers (5.71 and 4.41), leaves a range of values from 0.00 to 2.92 across 92 cases. With an even distribution across that range, one would expect that 51 percent of them would be in the range of 0.50-to-1 and 2.00-to-1. With only 19 percent of the cases being in that range, one is left to conclude that there is no clear correlation here. In fact, it clearly is the opposite effect, which is that there is a negative relationship. Not only is the RAND construct unsupported, it is clearly and soundly contradicted with this data. Furthermore, the RAND construct is theoretically a worse predictor of casualty rates than if one randomly selected a value for the percentile exchange rates between the range of 0 and 2.92. We do believe this data is appropriate and accurate for such a test.

As there are only 19 cases of 3:1 attacks falling in the even percentile exchange rate range, then we should probably look at these cases for a moment:

One will note, in these 19 cases, that the average attacker casualties are way out of line with the average for the entire data set (3.20 versus 1.39 or 3.20 versus 0.63 with pre-1943 and Soviet-doctrine attackers removed). The reverse is the case for the defenders (3.12 versus 6.08 or 3.12 versus 5.83 with pre-1943 and Soviet-doctrine attackers removed). Of course, of the 19 cases, 2 are pre-1943 cases and 7 are cases of Soviet-doctrine attackers (in fact, 8 of the 14 cases of the Soviet-doctrine attackers are in this selection of 19 cases). This leaves 10 other cases from the Mediterranean and ETO (Northwest Europe 1944). These are clearly the unusual cases, outliers, etc. While the RAND 3:1 rule may be applicable for the Soviet-doctrine offensives (as it applies to 8 of the 14 such cases we have), it does not appear to be applicable to anything else. By the same token, it also does not appear to apply to virtually any cases of post-WWII combat. This all strongly argues that not only is the RAND construct not proven, but it is indeed clearly not correct.

One will note, in these 19 cases, that the average attacker casualties are way out of line with the average for the entire data set (3.20 versus 1.39 or 3.20 versus 0.63 with pre-1943 and Soviet-doctrine attackers removed). The reverse is the case for the defenders (3.12 versus 6.08 or 3.12 versus 5.83 with pre-1943 and Soviet-doctrine attackers removed). Of course, of the 19 cases, 2 are pre-1943 cases and 7 are cases of Soviet-doctrine attackers (in fact, 8 of the 14 cases of the Soviet-doctrine attackers are in this selection of 19 cases). This leaves 10 other cases from the Mediterranean and ETO (Northwest Europe 1944). These are clearly the unusual cases, outliers, etc. While the RAND 3:1 rule may be applicable for the Soviet-doctrine offensives (as it applies to 8 of the 14 such cases we have), it does not appear to be applicable to anything else. By the same token, it also does not appear to apply to virtually any cases of post-WWII combat. This all strongly argues that not only is the RAND construct not proven, but it is indeed clearly not correct.

The fact that this construct also appears in Soviet literature, but nowhere else in US literature, indicates that this is indeed where the rule was drawn from. One must consider the original scenarios run for the RSAC [RAND Strategy Assessment Center] wargame were “Fulda Gap” and Korean War scenarios. As such, they were regularly conducting battles with Soviet attackers versus Allied defenders. It would appear that the 3:1 rule that they used more closely reflected the experiences of the Soviet attackers in WWII than anything else. Therefore, it may have been a fine representation for those scenarios as long as there was no US counterattacking or US offensives (and assuming that the Soviet Army of the 1980s performed at the same level as in did in the 1940s).

There was a clear relative performance difference between the Soviet Army and the German Army in World War II (see our Capture Rate Study Phase I & II and Measuring Human Factors in Combat for a detailed analysis of this).[1] It was roughly in the order of a 3-to-1-casualty exchange ratio. Therefore, it is not surprising that Soviet writers would create analytical tables based upon an equal percentage exchange of losses when attacking at 3:1. What is surprising, is that such a table would be used in the US to represent US forces now. This is clearly not a correct application.

Therefore, RAND’s SFS, as currently constructed, is calibrated to, and should only be used to represent, a Soviet-doctrine attack on first world forces where the Soviet-style attacker is clearly not properly trained and where the degree of performance difference is similar to that between the Germans and Soviets in 1942-44. It should not be used for US counterattacks, US attacks, or for any forces of roughly comparable ability (regardless of whether Soviet-style doctrine or not). Furthermore, it should not be used for US attacks against forces of inferior training, motivation and cohesiveness. If it is, then any such tables should be expected to produce incorrect results, with attacker losses being far too high relative to the defender. In effect, the tables unrealistically penalize the attacker.

As JICM with SFS is now being used for a wide variety of scenarios, then it should not be used at all until this fundamental error is corrected, even if that use is only for training. With combat tables keyed to a result that is clearly off by an order of magnitude, then the danger of negative training is high.

NOTES

[1] Capture Rate Study Phases I and II Final Report (The Dupuy Institute, March 6, 2000) (2 Vols.) and Measuring Human Factors in Combat—Part of the Enemy Prisoner of War Capture Rate Study (The Dupuy Institute, August 31, 2000). Both of these reports are available through our web site.

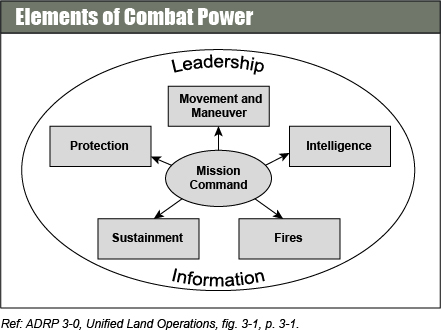

During this phase, planners are advised to account for “factors that are difficult to gauge, such as impact of past engagements, quality of leaders, morale, maintenance of equipment, and time in position. Levels of electronic warfare support, fire support, close air support, civilian support, and many other factors also affect arraying forces.” FM 6-0 offers no detail as to how these factors should be measured or applied, however.

During this phase, planners are advised to account for “factors that are difficult to gauge, such as impact of past engagements, quality of leaders, morale, maintenance of equipment, and time in position. Levels of electronic warfare support, fire support, close air support, civilian support, and many other factors also affect arraying forces.” FM 6-0 offers no detail as to how these factors should be measured or applied, however.