[This post is based on “Iranian Casualties in the Iran-Iraq War: A Reappraisal,” by H. W. Beuttel, originally published in the December 1997 edition of the International TNDM Newsletter.]

Posts in this series:

Iranian Casualties in the Iran-Iraq War: A Reappraisal

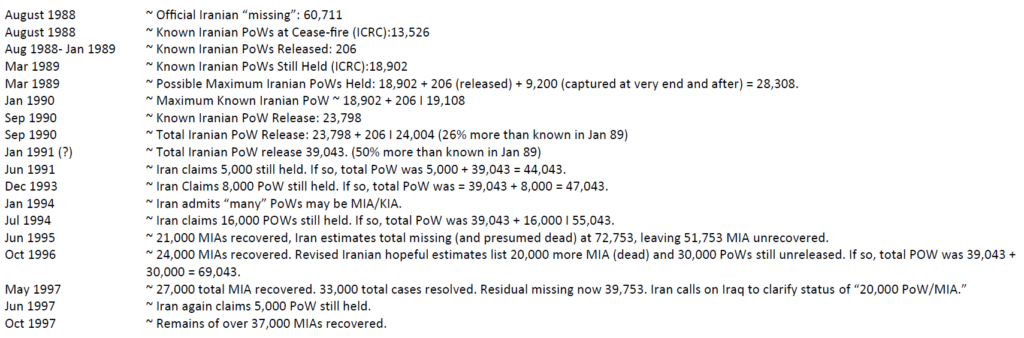

Iranian Missing In Action From The Iran-Iraq War

Iranian Prisoners of War From The Iran-Iraq War

The “Missing” Iranian Prisoners of War From The Iran-Iraq War

Iranian Killed And Died Of Wounds In The Iran-Iraq War

Iranian Wounded In Action In The Iran-Iraq War

Iranian Chemical Casualties In The Iran-Iraq War

Iranian Civil Casualties In The Iran-Iraq War

A Summary Estimate Of Iranian Casualties In The Iran-Iraq War

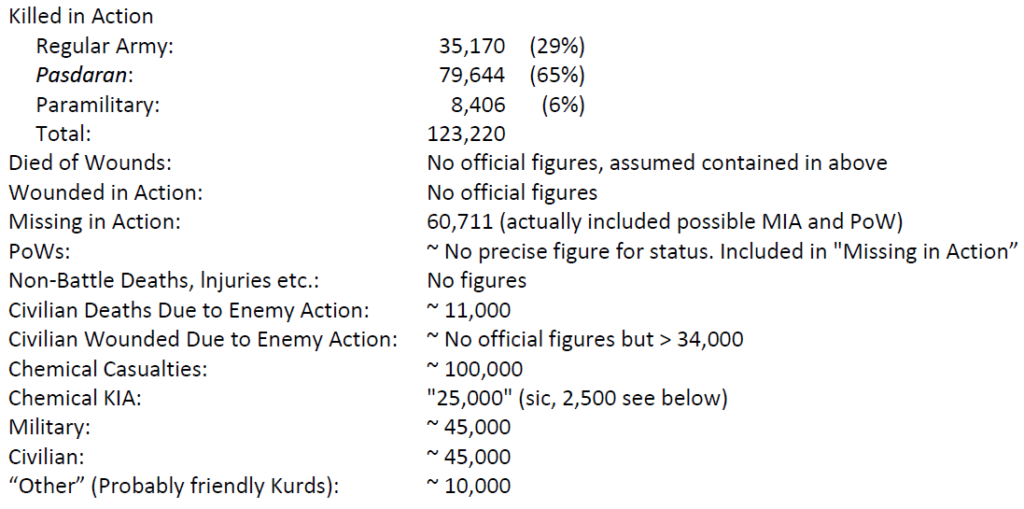

Killed and Died of Wounds

As early as 1984—only half way through the war—estimates of Iranian casualties were wildly exaggerated as equally as wildly divergent. Figure 2 illustrates this so-called “Thermometer of Death” widely believed in the West.

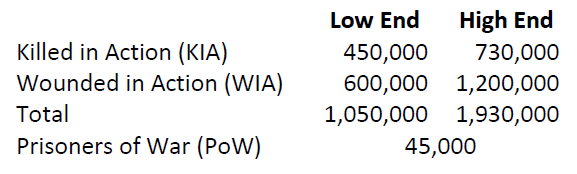

Of 72,753 currently estimated MIAs, virtually all are probably KIA. When this is added to the official KIA count of 123,230 we arrive at a total of 195,983 fallen.

Of 72,753 currently estimated MIAs, virtually all are probably KIA. When this is added to the official KIA count of 123,230 we arrive at a total of 195,983 fallen.

Another clue for total KIA total comes from the Behest-e Zahra Military Cemetery in Tehran. In this cemetery rest 36,000 fallen from Tehran Province alone.[77] The Iranian Army was (and is) a territorially based and mobilized entity. Depending on population base, the regions and provinces support various numbers and echelons of operational units. For example, the entire 1st Sarollah Corps is mobilized in Region 10 (Tehran) which has the largest population base. Kerman province, which is far less populous, is home to only the 41st Sarollah Division and the Zulfiqar Brigade.[78] Given this fact we may postulate that total casualties of all provinces are proportional to their populations. If so, the 36,000 KIA from Tehran Province (about 20% of Iran’s total population) represents about 20% of total KIA. This leads us to the calculation Total KIA = 36,000 * 5 = 180,000. This proportion is also confirmed by the mass ceremony for 3,000 recovered MIAs in February 1995. Six hundred of these were from Tehran Province, 20% of the total count in this instance.[79] Again, when 1,200 martyrs were buried nationwide in October 1997, 112 (or 17%) were from Tehran Province.

If we do a simple average of the two figures we arrive at somewhere in the vicinity of 188,000 KIA. The minimum is too low as all MIAs are not yet accounted for. I use the average rather than the maximum as I feel that probably several thousand of the missing were defectors or collaborators who joined the ranks of the Iraqi sponsored National Liberation Army of Iran. Iran recruited at least 10,000 Iraqi PoWs into their “Badr” Army of Iraqi expatriates to fight against Saddam Hussein.

The Moshen Rezui Excursion

In September of 1997, outgoing commander of the Pasdaran, Major General Moshen Rezai, cited some compelling statistics on Iranian casualties in the War of Sacred Defense. Speaking of the IRGC, he claimed some 2,000,000 Pasdaran served in combat over the course of the war. Of these 150,000 were martyred, 200,000 permanently disabled.[80] Taken at face value, these figures suggest KIA totals far higher than released in 1988. The Pasdaran are cited as taking some 90% more KIA than disclosed at war’s end. If the proportion is the same for the regular army, then it must have suffered some 66,000 KIA, and paramilitary deaths were on the order of 16,000. The total KIA would stand at 232,000. Another question is whether Rezai counted the MIAs, and if so how many were Pasdaran (and Baseej)? If he did and the proportion is constant (69%) then some 23,000 of 33,000 cases recovered or settled were Pasdaran (or Baseej). This in turn boosts the count by at least 11,000 (counting regular army and paramilitary recovered M1As) to about 243,000. As there are at least 39,000 still missing (and presumed dead) the final tally would be on the order of 282,000 military and paramilitary dead.

On the other hand Major General Rezai may have been speaking somewhat loosely to exaggerate his component’s contribution. He has been known to exaggerate before. The number of 150,000 KIA matches the sum of the announced dead (123,220) at war’s end plus officially announced recovered MIA bodies—27,000 as of June 1997—(remember: 6,000 MIAs have been simply declared dead at family request). 123,220 + 27,000 = 150,220. The remaining estimated 39,000 residual MIAs would bring the total count of military combat dead to 189,000, in line with above estimates.

Possible Clues to Non-Battle Deaths

Another piece of indirect evidence comes from the vast quantities of Iranian equipment captured by Iraqi forces between March and July 1988. These losses included 1,298 tanks, 155 infantry fighting vehicles, 512 armored personnel carriers, 365 pieces of artillery, 300 anti-aircraft guns, 6,196 mortars, 5,550 recoilless rifles, 8,050 RPG-7s, 60,164 assault rifles, 322 pistols, 501 engineer vehicles, 6,156 radios, 2,054 trucks and light vehicles, 16,863 items of NBC defense equipment and 24,257 caskets.[81] It is the caskets which are of interest.

These were obviously intended for Iranian dead. For an army that popular imagination saw as taking 10,000 dead in a single battle this was a paltry number, In early 1988 Iran had 600,000 troops on the battle front. 24,000 represent only 4% of this number. Interestingly, if this author’s calculation of Iranian KIA at circa 188,000 is correct, annual average war deaths would be roughly 188,000/8 or 23,500, almost the exact number of caskets. However, the Iranians did not know they were actually taking this many dead. They listed only 123,220 KIA at war’s end, not realizing how many “missing” (PoW/MIA) they really had and that over half of these were, in fact, dead. Expected annual war dead under their original figures would have been 123,000/8 = 15,000. This figure is 40% less than the casket cache total, but probably represented an Iranian planning factor for annual graves registration requirements at the front, but with a 60% hedge?

Sixty percent seems somewhat excessive. 10-25% is a more normal “fudge” factor. It may, however, provide a clue to the rate of Iranian non-battle deaths which would require caskets too. In the latter case this would indicate a non-battle-to- (then known) battle deaths ratio of roughly .6. This would represent something like 74,000 non-battle deaths (accident, disease, etc). Ground truth ratio (with now known MIA dead) would be .39. This is almost identical to U.S. experience in World War II (.36) and does not approach the World War I experience (1.43).[82]

Mr Beuttel, a former U.S. Army intelligence officer, was employed as a military analyst by Boeing Research & Development at the time of original publication. The views and opinions expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of The Boeing Company.

Armies have historically responded to the increasing lethality of weapons by dispersing mass in frontage and depth on the battlefield. Will combat see a new period of adjustment over the next 50 years like the previous half-century, where dispersion continues to shift in direct proportion to increased weapon range and precision, or will there be a significant change in the character of warfare?

Armies have historically responded to the increasing lethality of weapons by dispersing mass in frontage and depth on the battlefield. Will combat see a new period of adjustment over the next 50 years like the previous half-century, where dispersion continues to shift in direct proportion to increased weapon range and precision, or will there be a significant change in the character of warfare?