This post is a partial response to questions from one of our readers (Stilzkin). On the subject of force ratios in conventional combat….I know of no detailed discussion on the phenomenon published to date. It was clearly addressed by Clausewitz. For example:

At Leuthen Frederick the Great, with about 30,000 men, defeated 80,000 Austrians; at Rossbach he defeated 50,000 allies with 25,000 men. These however are the only examples of victories over an opponent two or even nearly three times as strong. Charles XII at the battle of Narva is not in the same category. The Russian at that time could hardly be considered as Europeans; moreover, we know too little about the main features of that battle. Bonaparte commanded 120,000 men at Dresden against 220,000—not quite half. At Kolin, Frederick the Great’s 30,000 men could not defeat 50,000 Austrians; similarly, victory eluded Bonaparte at the desperate battle of Leipzig, though with his 160,000 men against 280,000, his opponent was far from being twice as strong.

These examples may show that in modern Europe even the most talented general will find it very difficult to defeat an opponent twice his strength. When we observe that the skill of the greatest commanders may be counterbalanced by a two-to-one ratio in the fighting forces, we cannot doubt that superiority in numbers (it does not have to more than double) will suffice to assure victory, however adverse the other circumstances.

and:

If we thus strip the engagement of all the variables arising from its purpose and circumstance, and disregard the fighting value of the troops involved (which is a given quantity), we are left with the bare concept of the engagement, a shapeless battle in which the only distinguishing factors is the number of troops on either side.

These numbers, therefore, will determine victory. It is, of course, evident from the mass of abstractions I have made to reach this point that superiority of numbers in a given engagement is only one of the factors that determines victory. Superior numbers, far from contributing everything, or even a substantial part, to victory, may actually be contributing very little, depending on the circumstances.

But superiority varies in degree. It can be two to one, or three or four to one, and so on; it can obviously reach the point where it is overwhelming.

In this sense superiority of numbers admittedly is the most important factor in the outcome of an engagement, as long as it is great enough to counterbalance all other contributing circumstance. It thus follows that as many troops as possible should be brought into the engagement at the decisive point.

And, in relation to making a combat model:

Numerical superiority was a material factor. It was chosen from all elements that make up victory because, by using combinations of time and space, it could be fitted into a mathematical system of laws. It was thought that all other factors could be ignored if they were assumed to be equal on both sides and thus cancelled one another out. That might have been acceptable as a temporary device for the study of the characteristics of this single factor; but to make the device permanent, to accept superiority of numbers as the one and only rule, and to reduce the whole secret of the art of war to a formula of numerical superiority at a certain time and a certain place was an oversimplification that would not have stood up for a moment against the realities of life.

Force ratios were discussed in various versions of FM 105-5 Maneuver Control, but as far as I can tell, this was not material analytically developed. It was a set of rules, pulled together by a group of anonymous writers for the sake of being able to adjudicate wargames.

The only detailed quantification of force ratios was provided in Numbers, Predictions and War by Trevor Dupuy. Again, these were modeling constructs, not something that was analytically developed (although there was significant background research done and the model was validated multiple times). He then discusses the subject in his book Understanding War, which I consider the most significant book of the 90+ that he wrote or co-authored.

The only analytically based discussion of force ratios that I am aware of (or at least can think of at this moment) is my discussion in my upcoming book War by Numbers: Understanding Conventional Combat. It is the second chapter of the book: https://dupuyinstitute.dreamhosters.com/2016/02/17/war-by-numbers-iii/

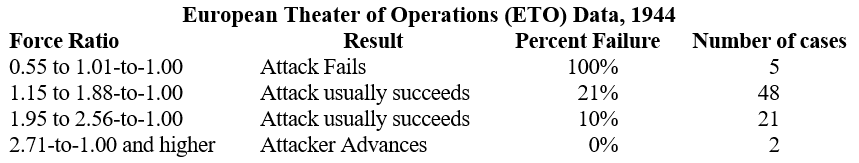

In this book, I assembled the force ratios required to win a battle based upon a large number of cases from World War II division-level combat. For example (page 18 of the manuscript):

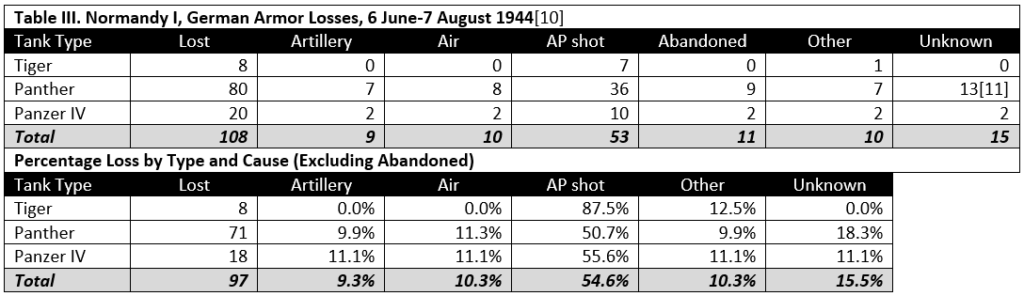

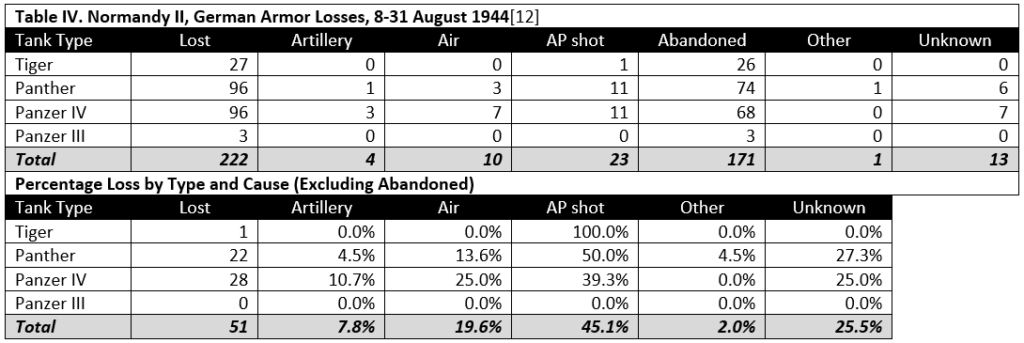

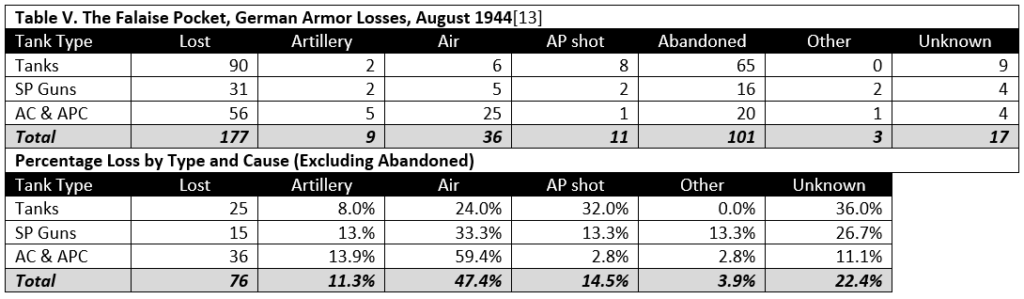

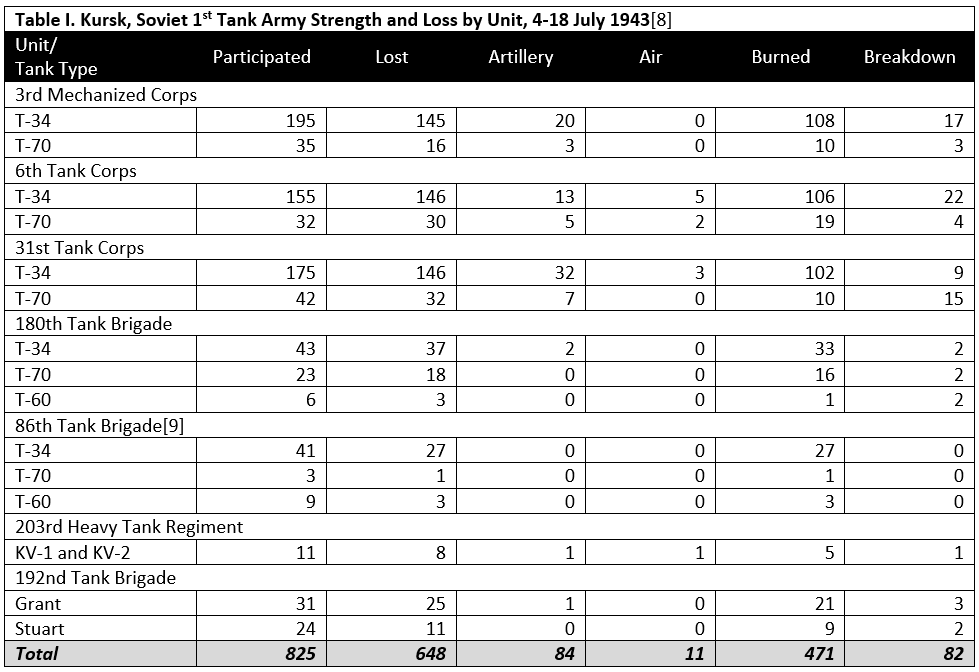

I did this for the ETO, for the battles of Kharkov and Kursk (Eastern Front 1943, divided by when the Germans are attacking and when the Soviets are attacking) and for PTO (Manila and Okinawa 1945).

I did this for the ETO, for the battles of Kharkov and Kursk (Eastern Front 1943, divided by when the Germans are attacking and when the Soviets are attacking) and for PTO (Manila and Okinawa 1945).

There is more than can be done on this, and we do have the data assembled to do this, but as always, I have not gotten around to it. This is why I am already considering a War by Numbers II, as I am already thinking about all the subjects I did not cover in sufficient depth in my first book.