I updated this post with tables! Click through to the original post and scroll to the bottom.

Excellence in Historical Research and Analysis

Excellence in Historical Research and Analysis

Tag combat

Human Factors In Warfare: Combat Intensity

Trevor Dupuy considered intensity to be another combat phenomena influenced by human factors. The variation in the intensity of combat is an aspect of battle that is widely acknowledged but little studied.

No one who has paid any attention at all to historical combat statistics can have failed to notice that some battles have been very bloody and hard-fought, while others—often under circumstances superficially similar—have reached a conclusion with relatively light casualties on one or both sides. I don’t believe that it is terribly important to find a quantitative reason for such differences, mainly because I don’t think there is any quantitative reason. The differences are usually due to such things as the general circumstances existing when the battles are fought, the personalities of the commanders, and the natures of the missions or objectives of one or both of the hostile forces, and the interactions of these personalities and missions.

From my standpoint the principal reason for trying to quantify the intensity of a battle is for purposes of comparative analysis. Just because casualties are relatively low on one or both sides does not necessarily mean that the battle was not intensive. And if the casualty rates are misinterpreted, then the analysis of the outcome can be distorted. For instance, a battle fought on a flat plain between two military forces will almost invariably have higher casualty rates for both sides than will a battle between those same two forces in mountainous terrain. A battle between those two forces in a heavy downpour, or in cold, wintry weather, will have lower casualties than when the forces are opposed to each other, under otherwise identical circumstances, in good weather. Casualty rates for small forces in a given set of circumstances are invariably higher than the rates for larger forces under otherwise identical circumstances.

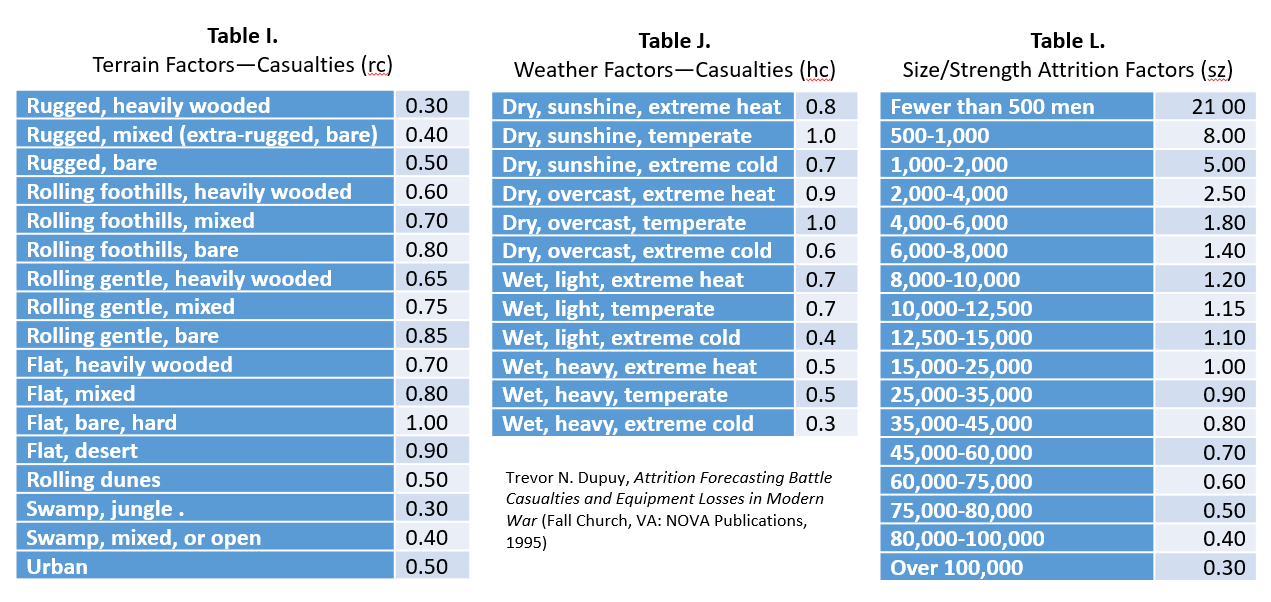

If all of these things are taken into consideration, then it is possible to assess combat intensity fairly consistently. The formula I use is as follows:

CI = CR / (sz’ x rc x hc)

When: CI = Combat Intensity Measure

CR = Casualty rate in percent per day

sz’ = Square root of sz, a factor reflecting the effect of size upon casualty rates, derived from historical experience

rc = The effect of terrain on casualty rates, derived from historical experience

hc = The effect of weather on casualty rates, derived from historical experience

I then (somewhat arbitrarily) identify seven levels of intensity:

0.00 to 0.49 Very low intensity (1)

0.50 to 0.99 Low intensity (56)

1.00 to 1.99 Normal intensity (213)

2.00 to 2.99 High intensity (101)

3.00 to 3.99 Very high intensity (30)

4.00 to 5.00 Extremely high intensity (17)

Over 5.00 Catastrophic outcome (20)

The numbers in parentheses show the distribution of intensity on each side in 219 battles in DMSi’s QJM data base. The catastrophic battles include: the Russians in the Battles of Tannenberg and Gorlice Tarnow on the Eastern Front in World War I; the Russians on the first day of the Battle of Kursk in July 1943; a British defeat in Malaya in December, 1941; and 16 Japanese defeats on Okinawa. Each of these catastrophic instances, quantitatively identified, is consistent with a qualitative assessment of the outcome.

[UPDATE]

As Clinton Reilly pointed out in the comments, this works better when the equation variables are provided. These are from Trevor N. Dupuy, Attrition Forecasting Battle Casualties and Equipment Losses in Modern War (Fall Church, VA: NOVA Publications, 1995), pp. 146, 147, 149.

Human Factors In Warfare: Surprise

Trevor Dupuy considered surprise to be one of the most important human factors on the battlefield.

A military force that is surprised is severely disrupted, and its fighting capability is severely degraded. Surprise is usually achieved by the side that has the initiative, and that is attacking. However, it can be achieved by a defending force. The most common example of defensive surprise is the ambush.

Perhaps the best example of surprise achieved by a defender was that which Hannibal gained over the Romans at the Battle of Cannae, 216 BC, in which the Romans were surprised by the unexpected defensive maneuver of the Carthaginians. This permitted the outnumbered force, aided by the multiplying effect of surprise, to achieve a double envelopment of their numerically stronger force.

It has been hypothesized, and the hypothesis rather conclusively substantiated, that surprise can be quantified in terms of the enhanced mobility (quantifiable) which surprise provides to the surprising force, by the reduced vulnerability (quantifiable) of the surpriser, and the increased vulnerability (quantifiable) of the side that is surprised.

I have written in detail previously about Dupuy’s treatment of surprise. He cited it as one of his timeless verities of combat. As one of the most powerful force multipliers available in battle, he calculated that achieving complete surprise could more than double the combat power of a force.

The U.S. Army’s Stryker Conundrum

As part of an initiative to modernize the U.S. Army in the late 1990s, then-Chief of Staff General Eric Shinseki articulated a need for combat units that were more mobile and rapidly deployable than the existing heavy armor brigades. This was the genesis of the Army’s medium-weight Stryker combat vehicle and the Stryker Brigade Combat Teams (SBCTs).

Since the Stryker’s introduction in 2002, SBCTs have participated successfully in U.S. expeditionary operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, validating for many the usefulness of Shinseki’s original medium-weight armor concept. However, changes in the strategic landscape and advances in technology and operational doctrine by potential adversaries are calling the medium armor concept back into question.

Medium armor faces the same conundrum that currently confronts the U.S. Army in general: should it optimize to conduct wide area security operations (which is the most likely type of future conflict) or combined arms maneuver (the most dangerous potential future conflict), or should it continue to hedge against strategic uncertainty by fielding a balanced, general purpose force which does a tolerable job of both, as it does now?

The Problem

In the current edition of Military Review, U.S. Army Captain Matthew D. Allgeyer presents an interesting critique of the Army’s existing medium-weight armor concept. He asserts that it is “is suffering from a lack of direction and focus…” Several improvements for the Stryker have been proposed based on perceptions of evolving Russian military capabilities, namely “a modern heavy-force threat supported by aviation assets.” The problem, according to Allgeyer, is that

The SBCT community wants all the positive aspects of a light force: lower cost, a small tooth-to-tail ratio, greater operational-level speed, etc. But, it also wants the ability to confront a heavy-armored force on its own terms without having to adopt the cost, support, and deployment time required by an armored force. Since these two ideas are mutuality exclusive, we have been forced to adopt a piecemeal response to shortcomings identified during training and training center rotations.

Even if the currently proposed improvements are adopted however, Allgeyer argues that updated Strykers would only provide the U.S. with a medium weight armor capability analogous to the 1960’s era Soviet motor-rifle regiment, a doctrinal step backward.

Allgeyer identifies the SBCT’s biggest weaknesses as a lack of firepower capable of successfully engaging enemy heavy armor and the absence of an organic air defense capability. Neither of these is a problem in wide area security missions such as peacekeeping or counterinsurgency, where deployability and mobility are priority considerations. However, both shortcomings are critical disadvantages in combined arms maneuver scenarios, particularly against Russian or Russian-equipped opposing forces.

Potential Solutions

These observations are not new. A 2001 TDI study of the historical effectiveness of lighter-weight armor pointed out its vulnerability to heavy armored forces, but also its utility in stability and contingency operations. The Russians long ago addressed these issues with their Bronetransporter (BTR)-equipped motor-rifle regiments by adding organic tank battalions to them, incorporating air defense platoons in each battalion, and upgunning the BTRs with 30mm cannons and anti-tank guided missiles (ATGMs).

The U.S. Army has similar solutions available. It has already sought to add 30mm cannons and TOW-2 ATGMs to the Styker. The Mobile Protected Firepower program that will provide a company of light-weight armored vehicles with high-caliber cannons to each infantry brigade combat team could easily be expanded to add a company or battalion of such vehicles to the SBCT. No proposals exist for improving air defense capabilities, but this too could be addressed.

Allgeyer agrees with the need for these improvements, but he is dissatisfied with the Army “simply reinventing on its own the wheel Russia made a long time ago.” His proposed “solution is a radical restructuring of thought around the Stryker concept.” He advocates ditching the term “Stryker” in favor of the more generic “medium armor” to encourage doctrinal thinking about the concept instead of the platform. Medium armor advocates should accept the need for a combined arms solution to engaging adversary heavy forces and incorporate more joint training into their mission-essential task lists. The Army should also do a better job of analyzing foreign medium armor platforms and doctrine to see what may be appropriate for U.S. adoption.

Allgeyer’s proposals are certainly worthy, but they may not add up to the radical restructuring he seeks. Even if adopted, they are not likely to change the fundamental characteristics of medium armor that make it more suitable to the wide area security mission than to combined arms maneuver. Optimizing it for one mission will invariably make it less useful for the other. Whether or not this is a wise choice is also the same question the Army must ponder with regard to its overall strategic mission.

Human Factors In Warfare: Defensive Posture

Like dispersion on the battlefield, Trevor Dupuy believed that fighting on the defensive derived from the effects of the human element in combat.

When men believe that their chances of survival in a combat situation become less than some value (which is probably quantifiable, and is unquestionably related to a strength ratio or a power ratio), they cannot and will not advance. They take cover so as to obtain some protection, and by so doing they redress the strength or power imbalance. A force with strength y (a strength less than opponent’s strength x) has its strength multiplied by the effect of defensive posture (let’s give it the symbol p) to a greater power value, so that power py approaches, equals, or exceeds x, the unenhanced power value of the force with the greater strength x. It was because of this that [Carl von] Clausewitz–who considered that battle outcome was the result of a mathematical equation[1]–wrote that “defense is a stronger form of fighting than attack.”[2] There is no question that he considered that defensive posture was a combat multiplier in this equation. It is obvious that the phenomenon of the strengthening effect of defensive posture is a combination of physical and human factors.

Dupuy elaborated on his understanding of Clausewitz’s comparison of the impact of the defensive and offensive posture in combat in his book Understanding War.

The statement [that the defensive is the stronger form of combat] implies a comparison of relative strength. It is essentially scalar and thus ultimately quantitative. Clausewitz did not attempt to define the scale of his comparison. However, by following his conceptual approach it is possible to establish quantities for this comparison. Depending upon the extent to which the defender has had the time and capability to prepare for defensive combat, and depending also upon such considerations as the nature of the terrain which he is able to utilize for defense, my research tells me that the comparative strength of defense to offense can range from a factor with a minimum value of about 1.3 to maximum value of more than 3.0.[3]

NOTES

[1] Dupuy believed Clausewitz articulated a fundamental law for combat theory, which Dupuy termed the “Law of Numbers.” One should bear in mind this concept of a theory of combat is something different than a fundamental law of war or warfare. Dupuy’s interpretation of Clausewitz’s work can be found in Understanding War: History and Theory of Combat (New York: Paragon House, 1987), 21-30.

[2] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, translation by Colonel James John Graham (London: N. Trübner, 1873), Book One, Chapter One, Section 17

[3] Dupuy, Understanding War, 26.

More On The U.S. Army’s ‘Identity Crisis’

The new edition of the U.S. Army War College’s quarterly journal Parameters contains additional commentary on the question of whether the Army should be optimizing to wage combined arms maneuver warfare or wide-area security/Security Force Assistance.

The new edition of the U.S. Army War College’s quarterly journal Parameters contains additional commentary on the question of whether the Army should be optimizing to wage combined arms maneuver warfare or wide-area security/Security Force Assistance.

Conrad Crane, the chief of historical services at the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center offers some comments and criticism of an article by Gates Brown, “The Army’s Identity Crisis” in the Winter 2016–17 issue of Parameters. Brown then responds to Crane’s comments.

Attrition In Future Land Combat

Last autumn, U.S. Army Chief of Staff General Mark Milley asserted that “we are on the cusp of a fundamental change in the character of warfare, and specifically ground warfare. It will be highly lethal, very highly lethal, unlike anything our Army has experienced, at least since World War II.” He made these comments while describing the Army’s evolving Multi-Domain Battle concept for waging future combat against peer or near-peer adversaries.

How lethal will combat on future battlefields be? Forecasting the future is, of course, an undertaking fraught with uncertainties. Milley’s comments undoubtedly reflect the Army’s best guesses about the likely impact of new weapons systems of greater lethality and accuracy, as well as improved capabilities for acquiring targets. Many observers have been closely watching the use of such weapons on the battlefield in the Ukraine. The spectacular success of the Zelenopillya rocket strike in 2014 was a convincing display of the lethality of long-range precision strike capabilities.

It is possible that ground combat attrition in the future between peer or near-peer combatants may be comparable to the U.S. experience in World War II (although there were considerable differences between the experiences of the various belligerents). Combat losses could be heavier. It certainly seems likely that they would be higher than those experienced by U.S. forces in recent counterinsurgency operations.

Unfortunately, the U.S. Defense Department has demonstrated a tenuous understanding of the phenomenon of combat attrition. Despite wildly inaccurate estimates for combat losses in the 1991 Gulf War, only modest effort has been made since then to improve understanding of the relationship between combat and casualties. The U.S. Army currently does not have either an approved tool or a formal methodology for casualty estimation.

Historical Trends in Combat Attrition

Trevor Dupuy did a great deal of historical research on attrition in combat. He found several trends that had strong enough empirical backing that he deemed them to be verities. He detailed his conclusions in Understanding War: History and Theory of Combat (1987) and Attrition: Forecasting Battle Casualties and Equipment Losses in Modern War (1995).

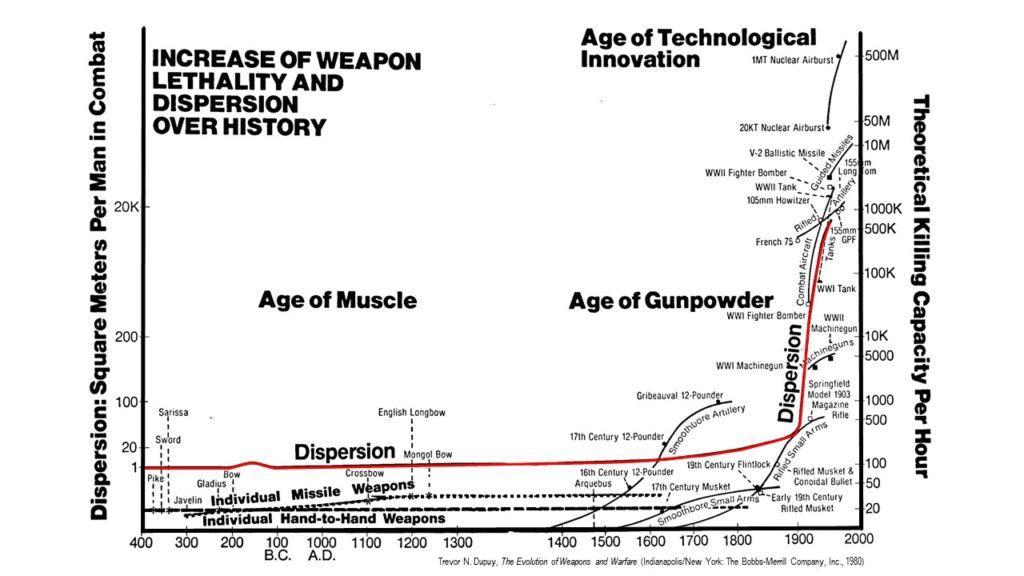

Dupuy documented a clear relationship over time between increasing weapon lethality, greater battlefield dispersion, and declining casualty rates in conventional combat. Even as weapons became more lethal, greater dispersal in frontage and depth among ground forces led daily personnel loss rates in battle to decrease.

The average daily battle casualty rate in combat has been declining since 1600 as a consequence. Since battlefield weapons continue to increase in lethality and troops continue to disperse in response, it seems logical to presume the trend in loss rates continues to decline, although this may not necessarily be the case. There were two instances in the 19th century where daily battle casualty rates increased—during the Napoleonic Wars and the American Civil War—before declining again. Dupuy noted that combat casualty rates in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War remained roughly the same as those in World War II (1939-45), almost thirty years earlier. Further research is needed to determine if average daily personnel loss rates have indeed continued to decrease into the 21st century.

The average daily battle casualty rate in combat has been declining since 1600 as a consequence. Since battlefield weapons continue to increase in lethality and troops continue to disperse in response, it seems logical to presume the trend in loss rates continues to decline, although this may not necessarily be the case. There were two instances in the 19th century where daily battle casualty rates increased—during the Napoleonic Wars and the American Civil War—before declining again. Dupuy noted that combat casualty rates in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War remained roughly the same as those in World War II (1939-45), almost thirty years earlier. Further research is needed to determine if average daily personnel loss rates have indeed continued to decrease into the 21st century.

Dupuy also discovered that, as with battle outcomes, casualty rates are influenced by the circumstantial variables of combat. Posture, weather, terrain, season, time of day, surprise, fatigue, level of fortification, and “all out” efforts affect loss rates. (The combat loss rates of armored vehicles, artillery, and other other weapons systems are directly related to personnel loss rates, and are affected by many of the same factors.) Consequently, yet counterintuitively, he could find no direct relationship between numerical force ratios and combat casualty rates. Combat power ratios which take into account the circumstances of combat do affect casualty rates; forces with greater combat power inflict higher rates of casualties than less powerful forces do.

Dupuy also discovered that, as with battle outcomes, casualty rates are influenced by the circumstantial variables of combat. Posture, weather, terrain, season, time of day, surprise, fatigue, level of fortification, and “all out” efforts affect loss rates. (The combat loss rates of armored vehicles, artillery, and other other weapons systems are directly related to personnel loss rates, and are affected by many of the same factors.) Consequently, yet counterintuitively, he could find no direct relationship between numerical force ratios and combat casualty rates. Combat power ratios which take into account the circumstances of combat do affect casualty rates; forces with greater combat power inflict higher rates of casualties than less powerful forces do.

Winning forces suffer lower rates of combat losses than losing forces do, whether attacking or defending. (It should be noted that there is a difference between combat loss rates and numbers of losses. Depending on the circumstances, Dupuy found that the numerical losses of the winning and losing forces may often be similar, even if the winner’s casualty rate is lower.)

Dupuy’s research confirmed the fact that the combat loss rates of smaller forces is higher than that of larger forces. This is in part due to the fact that smaller forces have a larger proportion of their troops exposed to enemy weapons; combat casualties tend to concentrated in the forward-deployed combat and combat support elements. Dupuy also surmised that Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz’s concept of friction plays a role in this. The complexity of interactions between increasing numbers of troops and weapons simply diminishes the lethal effects of weapons systems on real world battlefields.

Somewhat unsurprisingly, higher quality forces (that better manage the ambient effects of friction in combat) inflict casualties at higher rates than those with less effectiveness. This can be seen clearly in the disparities in casualties between German and Soviet forces during World War II, Israeli and Arab combatants in 1973, and U.S. and coalition forces and the Iraqis in 1991 and 2003.

Combat Loss Rates on Future Battlefields

What do Dupuy’s combat attrition verities imply about casualties in future battles? As a baseline, he found that the average daily combat casualty rate in Western Europe during World War II for divisional-level engagements was 1-2% for winning forces and 2-3% for losing ones. For a divisional slice of 15,000 personnel, this meant daily combat losses of 150-450 troops, concentrated in the maneuver battalions (The ratio of wounded to killed in modern combat has been found to be consistently about 4:1. 20% are killed in action; the other 80% include mortally wounded/wounded in action, missing, and captured).

It seems reasonable to conclude that future battlefields will be less densely occupied. Brigades, battalions, and companies will be fighting in spaces formerly filled with armies, corps, and divisions. Fewer troops mean fewer overall casualties, but the daily casualty rates of individual smaller units may well exceed those of WWII divisions. Smaller forces experience significant variation in daily casualties, but Dupuy established average daily rates for them as shown below.

For example, based on Dupuy’s methodology, the average daily loss rate unmodified by combat variables for brigade combat teams would be 1.8% per day, battalions would be 8% per day, and companies 21% per day. For a brigade of 4,500, that would result in 81 battle casualties per day, a battalion of 800 would suffer 64 casualties, and a company of 120 would lose 27 troops. These rates would then be modified by the circumstances of each particular engagement.

Several factors could push daily casualty rates down. Milley envisions that U.S. units engaged in an anti-access/area denial environment will be constantly moving. A low density, highly mobile battlefield with fluid lines would be expected to reduce casualty rates for all sides. High mobility might also limit opportunities for infantry assaults and close quarters combat. The high operational tempo will be exhausting, according to Milley. This could also lower loss rates, as the casualty inflicting capabilities of combat units decline with each successive day in battle.

It is not immediately clear how cyberwarfare and information operations might influence casualty rates. One combat variable they might directly impact would be surprise. Dupuy identified surprise as one of the most potent combat power multipliers. A surprised force suffers a higher casualty rate and surprisers enjoy lower loss rates. Russian combat doctrine emphasizes using cyber and information operations to achieve it and forces with degraded situational awareness are highly susceptible to it. As Zelenopillya demonstrated, surprise attacks with modern weapons can be devastating.

Some factors could push combat loss rates up. Long-range precision weapons could expose greater numbers of troops to enemy fires, which would drive casualties up among combat support and combat service support elements. Casualty rates historically drop during night time hours, although modern night-vision technology and persistent drone reconnaissance might will likely enable continuous night and day battle, which could result in higher losses.

Drawing solid conclusions is difficult but the question of future battlefield attrition is far too important not to be studied with greater urgency. Current policy debates over whether or not the draft should be reinstated and the proper size and distribution of manpower in active and reserve components of the Army hinge on getting this right. The trend away from mass on the battlefield means that there may not be a large margin of error should future combat forces suffer higher combat casualties than expected.

What Would An Army Optimized For Multi-Domain Battle Look Like?

As the U.S. Army develops its new Multi-Domain Battle (MDB) concept and seeks to modernize and upgrade its forces, some have called for optimizing its force structure for waging combined arms maneuver combat. What would such an Army force structure look like?

The active component of the Army currently consists of three corps, 10 divisions, 16 armored/Stryker brigade combat teams (BCTs), 15 light infantry BCTs, 12 combat aviation brigades, four fires brigades, three battlefield surveillance brigades, one engineer brigade, one Ranger brigade, five Special Forces groups, and a special operations aviation regiment.

U.S. Army Major Nathan A. Jennings and Lt. Col. Douglas Macgregor (ret.) have each proposed alternative force structure concepts designed to maximize the Army’s effectiveness for combined arms combat.

Jennings’s Realignment Model

Jennings’s concept flows directly from the precepts that MDB is being currently developed upon.

Designed to maximize diverse elements of joint, interorganizational and multinational power to create temporary windows of advantage against complex enemy systems, the Army’s incorporation of [MDB] should be accompanied by optimization of its order of battle to excel against integrated fire and maneuver networks.

To that end, he calls for organizing U.S. Army units into three types of divisions: penetration, exploitation and stabilization.

Empowering joint dynamism begins with creating highly mobile and survivable divisions designed to penetrate complex defenses that increasingly challenge aerial access. These “recon-strike” elements would combine armored and Stryker BCTs; special operations forces; engineers; and multifaceted air defense, indirect, joint, cyber, electromagnetic and informational fires to dislocate and disintegrate adversary defenses across theater depth. As argued by Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster, then-director of the Army Capabilities Integration Center, they could “fight their way through long-range weapons fire and gain physical contact with hard-to-find opponents” while striking “from unexpected directions with multiple forms of firepower.”

Exploitation divisions would employ more balanced capabilities to destroy enemy concentrations, clear contested zones and seize key terrain. Comprising a variety of light, airborne, motorized and mechanized infantry BCTs with modest armor and engineer support—all empowered by destructive kinetic, electronic and virtual fires—these commands would attack through windows of opportunity created by deep strikes to overmatch paralyzed defenders. While penetrating formations would rapidly bridge air and land component efforts, their more versatile and flexible exploitation counterparts would allow joint commands to decisively shatter adversary warfighting capabilities through intensive fire and maneuver.

The third type of division would be made up of elements trained to consolidate gains in order to set the conditions for a sustainable, stable environment, as required by Army doctrine. The command’s multifaceted brigades could include tailored civil affairs, informational, combat advisory, military police, light infantry, aviation and special operations elements in partnership with joint, interdepartmental, non-governmental and coalition personnel. These stabilization divisions would be equipped to independently follow penetration and exploitation forces to secure expanding frontages, manage population and resource disruptions, negotiate political turbulence, and support the re-establishment of legitimate security forces and governance.

Jennings did not specify how these divisions would be organized, how many of each type he would propose, or the mix of non-divisional elements. They are essentially a reorganization of current branch and unit types.

Proposing separate penetration and exploitation forces hearkens back to the earliest concepts of tank warfare in Germany and the Soviet Union, which envisioned infantry divisions creating breaches in enemy defenses, through which armored divisions would be sent to attack rear areas and maneuver at the operational level. Though in Jennings’s construction, the role of infantry and armor would be reversed.

Jennings’s envisioned force also preserves the capability for conducting wide area security operations in the stabilization divisions. However, since the stabilization divisions would likely constitute only a fraction of the overall force, this would be a net reduction in capability, as all of the current general purpose force units are (theoretically) capable of conducting wide area security. Jennings’s penetration and exploitation divisions would presumably possess more limited capability for this mission.

Macgregor’s Transformation Model

While Jenning’s proposed force structure can be seen as evolutionary, Macgregor’s is much more radically innovative. His transformation concept focuses almost exclusively on optimizing U.S. ground forces to wage combined arms maneuver warfare. Macgregor’s ideas stemmed from his experiences in the 1991 Gulf War and he has developed and expanded on them continuously since then. Although predating MDB, Macgregor’s concepts clearly influenced the thinking behind it and are easily compatible with it.

In a 2016 briefing for Senator Tom Cotton, Macgregor proposed the following structure for U.S. Army combat forces.

The heart of Macgregor’s proposal are modular, independent, all arms/all effects, brigade-sized combat groups that emphasize four primary capabilities: maneuver (mobile armored firepower for positional advantage), strike (stand-off attack systems), ISR (intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance) and sustainment (logistics). These modular groups would be the Army’s contribution to cross-domain, corps-level joint task forces, which is how he—and increasingly the rest of the U.S. armed forces—sees the U.S. military waging combat in the future.

Macgregor’s envisioned force structure adds his Reconnaissance Strike Group (RSG) to armored, mechanized infantry, and airborne/air-assault light infantry units. These would total 26 brigade-sized groups, down from the current 31 BCTs, with a ratio of 16 RSG/armored groups to 10 mechanized/airborne infantry.

Macgregor would also downsize the number of manned rotary wing combat aviation elements from 12 to four mostly be replacing them with drones integrated into the independent strike groups and into the strike battalions in the maneuver groups.

He would add other new unit types as well, including theater missile defense groups, C41I groups, and chem-bio warfare groups.

Macgregor’s proposed force structure would also constitute a net savings in overall manpower, mainly by cutting out division-level headquarters and pushing sustainment elements down to the individual groups.

Evolution or Revolution?

While both propose significant changes from the current organization, Jennings’s model is more conservative than Macgregor’s. Jennings would keep the division and BCT as the primary operational units, while Macgregor would cut and replace them altogether. Jennings clearly was influenced by Macgregor’s “strike-reconnaissance” concept in his proposal for penetration divisions. His description of them is very close to the way Macgregor defines his RSGs.

The biggest difference is that Jennings’s force would still retain some capacity to conduct wide area security operations, whether it be in conventional or irregular warfare circumstances. Macgregor has been vocal about his belief that the U.S. should avoid large-scale counterinsurgency or stabilization commitments as a matter of policy. He has also called into question the survivability of light infantry on future combined arms battlefields.

Even should the U.S. commit itself to optimizing its force structure for MDB, it is unclear at this point whether it would look like what Jennings or Macgregor propose. Like most military organizations, the U.S. Army is not known for its willingness to adopt radical change. The future Army force structure is likely to resemble its current form for some time, unless the harsh teachings of future combat experience dictate otherwise.

The U.S. Army’s Identity Crisis: Optimizing For Future Warfare

As the U.S. national security establishment grapples with the implications of the changing character of warfare in the early 21st century, one of more difficult questions to be addressed will be how to properly structure its land combat forces. After nearly two decades of irregular warfare, advocates argue that U.S land forces are in need of recapitalization and modernization. Their major weapons systems are aging and the most recent initiative to replace them was cancelled in 2009. While some upgrades have been funded on the margins, U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps leaders have also committed to developing a new warfighting doctrine—Multi-Domain Battle (MDB)—to meet the potential challenges of 21st century warfare.

Because conflicts arising from Great Power rivalries and emerging regional challenges pose the greatest potential strategic danger to the U.S., some have called for optimizing the Army to execute combined arms maneuver warfare against peer or near-peer armies. Recent experience suggests however that the most likely future conflicts the U.S. will engage in will involve ongoing post-Cold War ethnic and nationalist-driven political violence, leading others to support a balanced force structure also capable of conducting wide-area security, or stabilization operations and counterinsurgency.

The Army attempted in 2011 to define wide-area security and combined arms maneuver as the two core competencies in its basic doctrine that would allow it to best prepare for these contingencies. By 2016, Army doctrine abandoned specific competencies in favor of the ability to execute “unified land operations,” broadly defined as “simultaneous offensive, defensive, and stability or defense support of civil authorities tasks to seize, retain, and exploit the initiative and consolidate gains to prevent conflict, shape the operational environment, and win our Nation’s wars as part of unified action.”

The failure to prioritize strategic missions or adequately fund modernization leaves the Army in the position of having to be ready to face all possible contingencies. Gates Brown claims this is inflicting an identity crisis on the Army that jeopardizes its combat effectiveness.

[B]y training forces for all types of wars it ends up lessening combat effectiveness across the entire spectrum. Instead of preparing inadequately for every war, the Army needs to focus on a specific skill set and hone it to a sharp edge… [A] well-defined Army can scramble to remedy known deficiencies in combat operations; however, consciously choosing not to set a deliberate course will not serve the Army well.

The Army’s Identity Crisis

To this point, the Army has relied on a balanced mix of land combat forces divided between armor (heavy tracked and medium wheeled) and light infantry formations. Although optimized for neither combined arms maneuver nor wide-area security, these general purpose forces have heretofore demonstrated the capability to execute both missions tolerably well. The Active Army currently fields 10 divisions comprising 31 Brigade Combat Teams (BCTs) almost evenly split between armor/mechanized and infantry (16 armored/Stryker and 15 infantry).

Major Nathan Jennings contends that the Army force structure should be specifically reorganized for combined arms maneuver and MDB.

Designed to maximize diverse elements of joint, interorganizational and multinational power to create temporary windows of advantage against complex enemy systems, the Army’s incorporation of the idea should be accompanied by optimization of its order of battle to excel against integrated fire and maneuver networks. To that end, it should functionalize its tactical forces to fight as penetration, exploitation and stabilization divisions with corresponding expertise in enabling the vast panoply of American and allied coercive abilities.

This forcewide realignment would enable “flexible and resilient ground formations [to] project combat power from land into other domains to enable joint force freedom of action,” as required by Gen. David G. Perkins, commander of the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command. While tailored brigades and battalions would feature combined arms with the ability to maneuver in a dispersed manner, optimized divisions would allow functional expertise in rear, close, deep and non-linear contests while maintaining operational tempo throughout rapid deep attacks, decisive assaults, and consolidation of gains. The new order would also bridge tactical and operational divides to allow greater cross-domain integration across the full range of military operations.

On the other hand, Lieutenant Colonel Jason Nicholson advocates heeding the lessons of the last decade and a half of U.S. experience with irregular warfare and fielding an upgraded, yet balanced, force structure. He does not offer a prescription for a proper force mix, but sees the recent Army decision to stand up six Security Force Assistance Brigades (SFABs) as an encouraging development.

The last sixteen years of ongoing military operations have been conducted at the expense of future requirements of all types. The modernization problems presented by “small wars” challenge the Army as surely as those related to high-intensity conflicts. While SFABs are a step in the right direction, greater investment is required to maximize the lessons learned after sixteen years of counterinsurgency. Training for specific missions like combat advising and security force assistance should be institutionalized for tactical units beyond the designated SFABs. The need for additional capabilities for operating in austere environments will also drive equipment requirements such as lighter power generation and enhanced tactical mobility. Greater expeditionary logistics, armor, and fire support assets will also be critical in future operations. Hybrid warfare, from the Russian campaign in Ukraine to the French campaign in Mali, will continue to change the nature of “small wars.” Megacities, climate change, and other similar challenges will require the same attention to detail by the Army as near-peer conflict in order to ensure future operational success.

No Simple Answers To Strategic Insolvency

Decisions regarding the Army’s force structure will be in the hands of senior political and military decision-makers and will require hard choices and accepting risks. Proponents of optimizing for combined arms maneuver concede that future U.S. commitments to counterinsurgency or large-scale stabilization operations would likely have to be curtailed. Conversely, a balanced force structure is a gamble that either conventional war is unlikely to occur or that general purpose forces are still effective enough to prevail in an emergency.

Hal Brands and Eric Edelman argue that the U.S. currently faces a crisis of “strategic insolvency” due to the misalignment of military capabilities with geopolitical ends in foreign policy, caused by the growth in strategic and geopolitical challenges combined with a “disinvestment” in defense resources. They contend that Great Powers have traditionally restored strategic solvency in three ways:

- “First, they can decrease commitments thereby restoring equilibrium with diminished resources.”

- “Second, they can live with greater risk by gambling that their enemies will not test vulnerable commitments or by employing riskier approaches—such as nuclear escalation—to sustain commitments on the cheap.”

- “Third, they can expand capabilities, thereby restoring strategic solvency.”

Brands and Edelman contend that most commentators favor decreasing foreign policy commitments. Thus far, the U.S. has seemingly adopted the second option–living with greater risk—by default, simply by avoiding choosing to reduce foreign policy commitments or to boost defense spending.

The administration of President Donald Trump is discovering, however, that simply choosing one course over another can be politically problematic. On the campaign trail in 2016, Trump called for expanding U.S. military capability, including increasing U.S. Army end strength to 540,000, rebuilding the U.S. Navy to at least 350 vessels, adding 100 fighter and attack aircraft to boost the U.S. Air Force to 1,200 aircraft, and boosting the U.S. Marine Corps from 24 battalions to 36. He signed an executive order after assuming office mandating this expansion, stating that his administration will pursue an as-yet undefined policy of “peace through strength.”

Estimates for the cost of these additional capabilities range from $55-$95 billion in additional annual defense spending. Trump called for an additional $54 billion spending on defense in his FY 2018 budget proposal. Secretary of Defense James Mattis told members of Congress that while the additional spending will help remedy short-term readiness challenges, it is not enough to finance the armed services plans for expansion and modernization. As Congress wrangles over a funding bill, many remain skeptical of increased government spending and it is unclear whether even Trump’s proposed increase will be approved.

Trump also said during the campaign that as president, he would end U.S. efforts at nation-building, focusing instead on “foreign policy realism” dedicated to destroying extremist organizations in conjunction with temporary coalitions of willing allies regardless of ideological or strategic differences. However, Trump has expressed ambivalent positions on intervention in Syria. While he has stated that he would not deploy large numbers of U.S. troops there, he also suggested that the U.S. could establish “safe zones” His cabinet has reportedly debated plans to deploy up to tens of thousands of ground troops in Syria in order to clear the Islamic State out, protect local populations, and encourage the return of refugees.

It does not appear as if the Army’s identity crisis will be resolved any time soon. If the past is any indication, the U.S. will continue to “muddle through” on its foreign policy, despite the risks.

New WWII German Maps At The National Archives

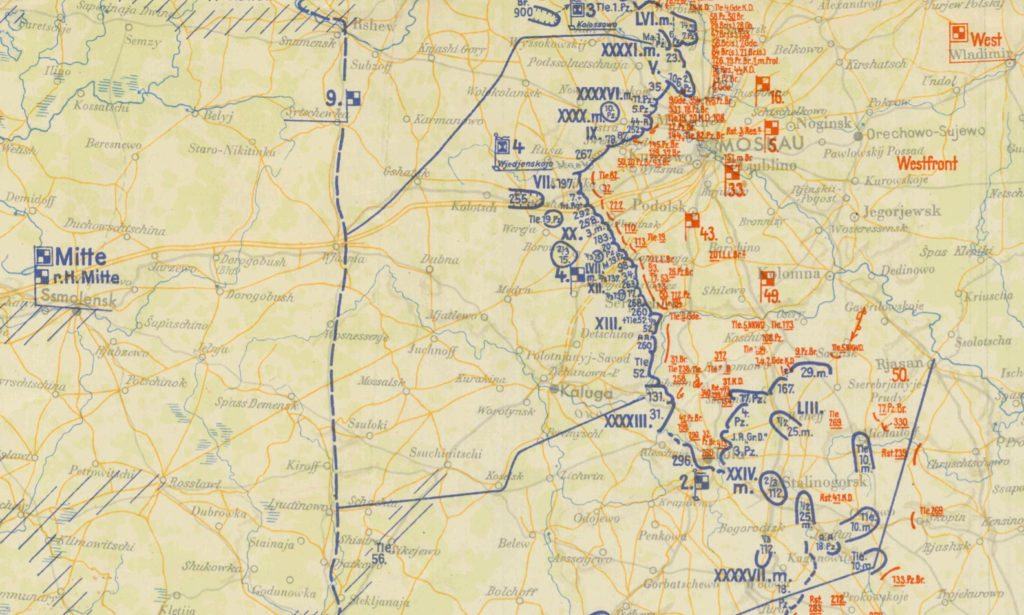

The Special Media Archives Services Division of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington, D.C. announced on it’s blog, The Unwritten Record, the recent opening of two new series in Record Group 242: National Archives Collection of Foreign Records Seized. The new series are German Situation Maps of the Western Front, 1944-1945 (NAID 40432392) and Various German World War II Maps, 1939-1945 (NAID 40480105).

The collections contain photographic reproductions of a full map of Germany including how many states in Germany existed at the time, as well as reproductions of various daily situation report maps created by the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (Armed Forces High Command) and Oberkommando des Heeres (Army High Command) to brief Adolph Hitler and senior German leaders. They show friendly (blue) and enemy (red) forces down to the division and detachment level. The original maps were captured by U.S. forces, which were later duplicated and then returned to the Germans.

Maps. Beautiful Maps

The NARA blog post includes several wonderful, high-quality digital scans in JPG format, although a quick check of the online NARA catalogue shows that these digital maps have yet to be posted online. As the existence of the images in the post show, however, this cannot be too far behind.

The maps themselves are priceless historical records containing truly amazing amounts of information. A portion of the Lage Ost (Situation East) map for 6 December 1941, above, is particularly notable. It depicts the military situation at what can be argued as the high tide of German fortunes in World War II, with its forces closing in on Moscow. However, 6 December was also the beginning of the great Soviet winter counteroffensive that would drive the German Army permanently away from Moscow.

A Map Is Worth At Least A Thousand Words

Several details immediately jump out. The northern prong of the German offensive, led by the Third Panzer Group and Forth Panzer Group, and the southern thrust by the Second Panzer Army can be clearly seen. While Second Panzer Army’s divisions are concentrated for the push from Tula northward, the army’s eastern flank is merely screened by elements of the 10th and 25th Motorized Infantry divisions, the 112th Infantry Division, and a detachment of the 18th Panzer Division. Large-scale, abstract maps of the war on the Eastern Front often depict the battle lines as solid, when in fact, they were thinly-held or gapped.

This is significant because of what this map does not depict: the several dozen divisions the Soviets had amassed around Moscow for their counter-offensive. In fact, the first Red Army counterattacks had started on 5 December, against the LVI Panzer Corps, north of Moscow (at the top of image above). Soviet maskirovka, or military deception efforts, had successfully hidden the build-up from German intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance assets. Soviet troops infiltrated these gaps, forcing the Germans to halt their attack and then withdraw to avoid encirclement.

This is only a fraction of the story contained in these maps. Hopefully, NARA is diligently digitizing the rest of the collection and will get them online as soon as possible,