Earlier this year, I noted that the U.S. is investing in upgrading its long range strike capabilities as part of its multi-domain battle doctrinal response to improving Chinese, Russian, and Iranian anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities. There have been a few updates on the progress of those investments.

The U.S. Army Long Range Fires Cross Functional Team

A recent article in Army Times by Todd South looked at some of the changes being implemented by the U.S. Army cross functional team charged with prioritizing improvements in the service’s long range fires capabilities. To meet a requirement to double the ranges of its artillery systems within five years, “the Army has embarked upon three tiers of focus, from upgrading old school artillery cannons, to swapping out its missile system to double the distance it can fire, and giving the Army a way to fire surface-to-surface missiles at ranges of 1,400 miles.”

The Extended Range Cannon Artillery program is working on rocket assisted munitions to double the range of the Army’s workhouse 155mm guns to 24 miles, with some special rounds capable of reaching targets up to 44 miles away. As I touched on recently, the Army is also looking into ramjet rounds that could potentially increase striking range to 62 miles.

To develop the capability for even longer range fires, the Army implemented a Strategic Strike Cannon Artillery program for targets up to nearly 1,000 miles, and a Strategic Fires Missile effort enabling targeting out to 1,400 miles.

The Army is also emphasizing retaining trained artillery personnel and an improved training regime which includes large-scale joint exercises and increased live-fire opportunities.

Revised Long Range Fires Doctrine

But better technology and training are only part of the solution. U.S. Army Captain Harrison Morgan advocated doctrinal adaptations to shift Army culture away from thinking of fires solely as support for maneuver elements. Among his recommendations are:

- Increasing the proportion of U.S. corps rocket artillery to tube artillery systems from roughly 1:4 to something closer to the current Russian Army ratio of 3:4.

- Fielding a tube artillery system capable of meeting or surpassing the German-made PZH 2000, which can strike targets out to 30 kilometers with regular rounds, sustain a firing rate of 10 rounds per minute, and strike targets with five rounds simultaneously.

- Focus on integrating tube and rocket artillery with a multi-domain, joint force to enable the destruction of the majority of enemy maneuver forces before friendly ground forces reach direct-fire range.

- Allow tube artillery to be task organized below the brigade level to provide indirect fires capabilities to maneuver battalions, and make rocket artillery available to division and brigade commanders. (Morgan contends that the allocation of indirect fires capabilities to maneuver battalions ended with the disbanding of the Army’s armored cavalry regiments in 2011.)

- Increase training in use of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) assets at the tactical level to locate, target, and observe fires.

U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy Face Long Range Penetrating Strike Challenges

The Army’s emphasis on improving long range fires appears timely in light of the challenges the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy face in conducting long range penetrating strikes mission in the A2/AD environment. A fascinating analysis by Jerry Hendrix for the Center for a New American Security shows the current strategic problems stemming from U.S. policy decisions taken in the early 1990s following the end of the Cold War.

In an effort to generate a “peace dividend” from the fall of the Soviet Union, the Clinton administration elected to simplify the U.S. military force structure for conducting long range air attacks by relieving the Navy of its associated responsibilities and assigning the mission solely to the Air Force. The Navy no longer needed to replace its aging carrier-based medium range bombers and the Air Force pushed replacements for its aging B-52 and B-1 bombers into the future.

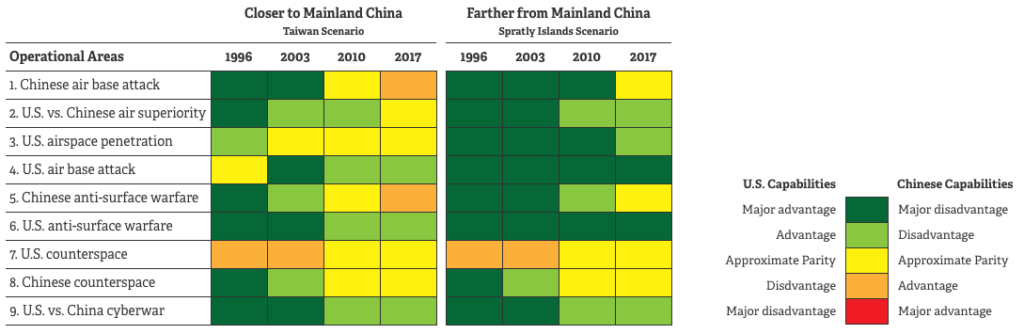

Both the Air Force and Navy emphasized development and acquisition of short range tactical aircraft which proved highly suitable for the regional contingencies and irregular conflicts of the 1990s and early 2000s. Impressed with U.S. capabilities displayed in those conflicts, China, Russia, and Iran invested in air defense and ballistic missile technologies specifically designed to counter American advantages.

The U.S. now faces a strategic environment where its long range strike platforms lack the range and operational and technological capability to operate within these AS/AD “bubbles.” The Air Force has far too few long range bombers with stealth capability, and neither the Air Force nor Navy tactical stealth aircraft can carry long range strike missiles. The missiles themselves lack stealth capability. The short range of the Navy’s aircraft and insufficient numbers of screening vessels leave its aircraft carriers vulnerable to ballistic missile attack.

Remedying this state of affairs will take time and major investments in new weapons and technological upgrades. However, with certain upgrades, Hendrix sees the current Air Force and Navy force structures capable of providing the basis for a long range penetrating strike operational concept effective against A2/AD defenses. The unanswered question is whether these upgrades will be implemented at all.

The U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command has released a revised draft version of its

The U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command has released a revised draft version of its