In 2011, the Office of the Secretary of Defense’s (OSD) Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE) disbanded its campaign-level modeling capabilities and reduced its role in the Department of Defense’s strategic analysis activity (SSA) process. CAPE, which was originally created in 1961 as the Office of Systems Analysis, “reports directly to the Secretary and Deputy Secretary of Defense, providing independent analytic advice on all aspects of the defense program, including alternative weapon systems and force structures, the development and evaluation of defense program alternatives, and the cost-effectiveness of defense systems.”

According to RAND’s Paul K. Davis, CAPE’s decision was controversial within DOD, and due in no small part to general dissatisfaction with the overall quality of strategic analysis supporting decision-making.

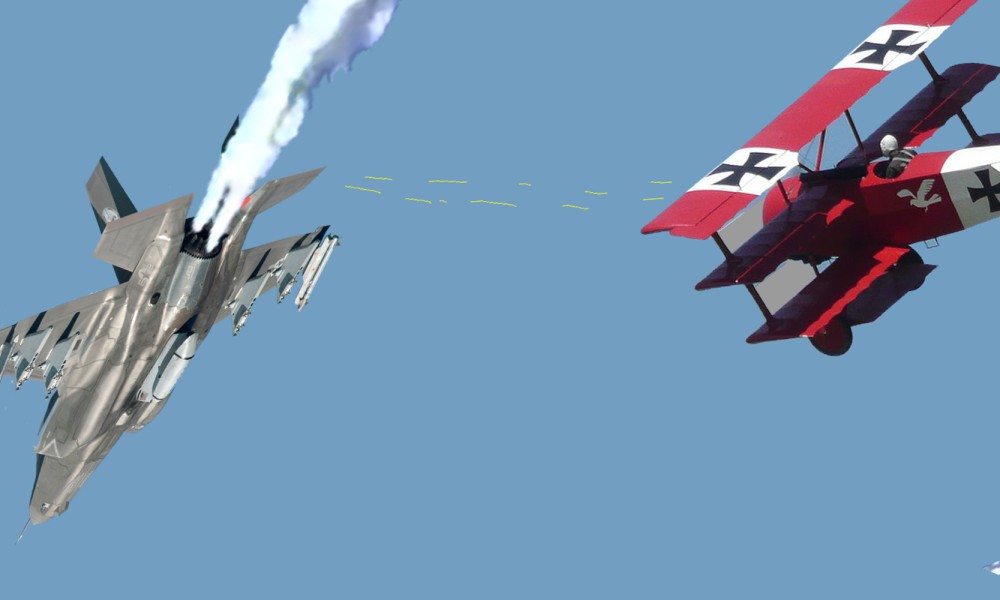

CAPE’s decision reflected a conclusion, accepted by the Secretary of Defense and some other senior leaders, that the SSA process had not helped decisionmakers confront their most-difficult problems. The activity had previously been criticized for having been mired in traditional analysis of kinetic wars rather than counterterrorism, intervention, and other “soft” problems. The actual criticism was broader: Critics found SSA’s traditional analysis to be slow, manpower-intensive, opaque, difficult to explain because of its dependence on complex models, inflexible, and weak in dealing with uncertainty. They also concluded that SSA’s campaign-analysis focus was distracting from more-pressing issues requiring mission-level analysis (e.g., how to defeat or avoid integrated air defenses, how to defend aircraft carriers, and how to secure nuclear weapons in a chaotic situation).

CAPE took the criticism to heart.

CAPE felt that the focus on analytic baselines was reducing its ability to provide independent analysis to the secretary. The campaign-modeling activity was disbanded, and CAPE stopped developing the corresponding detailed analytic baselines that illustrated, in detail, how forces could be employed to execute a defense-planning scenario that represented strategy.

However, CAPE’s solution to the problem may have created another. “During the secretary’s reviews for fiscal years 2012 and 2014, CAPE instead used extrapolated versions of combatant commander plans as a starting point for evaluating strategy and programs.”

As Davis, related, there were many who disagreed with CAPE’s decision at the time because of the service-independent perspective it provided.

Some senior officials believed from personal experience that SSA had been very useful for behind-the-scenes infrastructure (e.g., a source of expertise and analytic capability) and essential for supporting DoD’s strategic planning (i.e., in assessing the executability of force-sizing strategy). These officials saw the loss of joint campaign-analysis capability as hindering the ability and willingness of the services to work jointly. The officials also disagreed with using combatant commander plans instead of scenarios as starting points for review of midterm programs, because such plans are too strongly tied to present-day thinking. (Emphasis added)

Five years later, as DOD gears up to implement the new Third Offset Strategy, it appears that the changes implemented in SSA in 2011 have not necessarily improved the quality of strategic analysis. DOD’s lack of an independent joint, campaign-level modeling capability is apparently hampering the ability of senior decision-makers to critically evaluate analysis provided to them by the services and combatant commanders.

In the current edition of Joint Forces Quarterly, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s military and security studies journal, Timothy A. Walton, a Fellow in the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, recommended that in support of “the Third Offset Strategy, the next Secretary of Defense should reform analytical processes informing force planning decisions.” He pointed suggested that “Efforts to shape assumptions in unrealistic or imprudent ways that favor outcomes for particular Services should be repudiated.”

As part of the reforms, Walton made a strong and detailed case for reinstating CAPE’s campaign-level combat modeling.

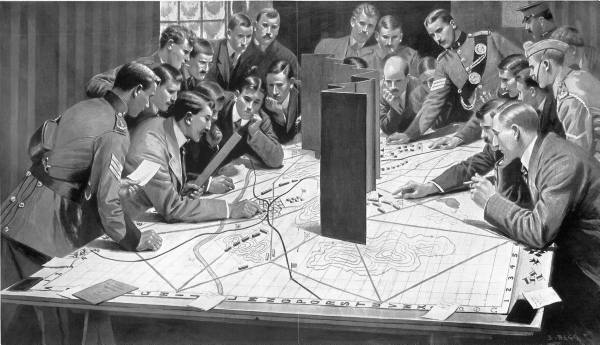

In terms of assessments, the Secretary of Defense should direct the Director of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation to reinstate the ability to conduct OSD campaign-level modeling, which was eliminated in 2011. Campaign-level modeling consists of the use of large-scale computer simulations to examine the performance of a full fielded military in planning scenarios. It takes the results of focused DOD wargaming activities, as well as inputs from more detailed tactical modeling, to better represent the effects of large-scale forces on a battlefield. Campaign-level modeling is essential in developing insights on the performance of the entire joint force and in revealing key dynamic relationships and interdependencies. These insights are instrumental in properly analyzing complex factors necessary to judge the adequacy of the joint force to meet capacity requirements, such as the two-war construct, and to make sensible, informed trades between solutions. Campaign-level modeling is essential to the force planning process, and although the Services have their own campaign-level modeling capabilities, OSD should once more be able to conduct its own analysis to provide objective, transparent assessments to senior decisionmakers. (Emphasis added)

So, it appears that DOD can’t quit combat modeling. But that raises the question, if CAPE does resume such activities, will it pick up where it left off in 2011 or do it differently? I will explore that in a future post.

!["The Ultimate Sand Castle" [Flickr, Jon]](https://dupuyinstitute.dreamhosters.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Ultimate_Sand_Castle-680x1024.jpg)

![Photograph of Russian T-90 tank following a hit by a U.S.-made TOW missile in Syria. [War Is Boring.com]](https://dupuyinstitute.dreamhosters.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/t_907.jpg)