The U.S. Air Force (USAF) has fielded a formidable force, demonstrating air dominance in conflicts fought, as well as those threatened, across the globe for decades through the Cold War (1945-1991); think Strategic Air Command (SAC) under Gen Curtis LeMay. Pax Americana has been further extended to the present. A “pax” (Latin for peace) being a period of relative peace due to a preponderance of power. The French Foreign Minister Hubert Vedrine famously defined the U.S. as a “hyperpower”, or “a country that is dominant or predominant in all categories” (NY Times, 1999-02-05). The ability to project power by the U.S. military, especially by the USAF, is and was unparalleled.

According to Gen David Goldfein, Air Force Chief of Staff, “We’re everywhere. Air power has become the oxygen the joint team breathes. Have it, you don’t even think about [it]. Don’t have it, it’s all you think about. Air superiority, ISR [Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance], space, lift [airlift, or transport services] are just a few examples.”

Indeed, “Land-based forces now are going to have to penetrate denied areas to facilitate air and naval forces. This is exact opposite of what we have done for the last 70 years, where air and naval forces have enabled ground forces,” according to General Mark Milley, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army. War on the Rocks claims “there is no end in sight to the [U.S.] Army’s dependence on airpower.”

The USAF Fights as a Joint Force

The photo above illustrates a joint team across U.S. and allied forces, by combining assets from the USAF, the U.S. Marine Corps (USMC), as well as the Royal Air Force (RAF), and Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) into a single fighting force. But it also demonstrates this preponderance of power by the USAF, which provided almost all of the aircraft used by the operation. Pictured aircraft include (clockwise from left):

- U-2S (USAF) – provides ISR.

- PAC-3 (USAF) – surface-to-air missile to attack airborne targets.

- KC-10 (USAF) – provide in-flight refueling services.

- F-15E (USAF) – provides both air superiority and precision strike capabilities.

- E-3D Sentry (RAF or USAF) – provides command, control, communications and computers, plus ISR, which happily forms the unique acronym C4ISR, rather than “CCCCISR”

- F/A-18C (USMC or RAAF) – provides both air superiority and precision strike capabilities.

- F/A-22 (USAF) – provides penetrating strike and air dominance capabilities.

- A330 MRTT (RAF?) – provides both in-flight refueling and airlift services.

- Emergency Medical and Firefighting ground vehicles.

- RQ-4 Global Hawk (USAF) – Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) providing ISR.

Thus, I’d assert, we have seen some strong evidence of great plans, and more importantly a planning capability by the U.S. military, including and especially the USAF.

The USAF Faces Some Significant Challenges

According to a RAND study on the USAF pilot shortage, the real issue is experience levels in “Operational Units (i.e., those with combat responsibilities) are the only assignment options for newly trained pilots while they mature and develop their mission knowledge. Thus, these units require enough experienced pilots to supervise the development of the new pilots. As the proportion of experienced pilots in a unit drops, each one must fly more to provide essential supervision to an increasing number of new pilots. If the unit’s flying capacity cannot increase, new pilots each fly less, extending the time they need to become experienced themselves.”

Given that the career path from military pilot to airlines pilot has been in operation since the 1940’s, why should this be a critical issue now? Because the difference in pay has changed. “The Air Force believes much of the problem comes from commercial airlines that have been hiring at increased rates and can offer bigger paychecks.” All major U.S. Airlines, however, must report not only pilot quantities and salaries, but many other financial details to the Office of Airline Information (OAI), which provides this data to the public for free. Does the USAF not have the capability to analyze and manage the economics of pilot demand and supply? It seems they have been caught reacting, rather than proactively managing their most critical resource, trained human pilots.

“Drone pilots suffer a high rate of burnout, as they work 12 to 13 hour days, performing mainly intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance missions, but also some strikes where mistakes caused by tired eyes can cost lives.” Given the autopilot capabilities of commercial airliners, why are Remotely Piloted Aircraft (RPA) aircrews working so much? Why has autonomy not been granted to a machine for the long, boring and tedious tasks of loiter, and then a human alerted when required to make decisions? Perhaps because the RPA concept is not developed enough to allow for man-machine teaming, perhaps because military leaders do not trust technology to deliver the right alerts.

- According to Goldfein, “I believe it’s a crisis: air superiority is not an American birthright. It’s actually something you have to fight for and maintain.”

As fighter pilots seem to be more likely to leave the USAF, these issues seem to be related. As “drones” (more properly RPA) became the star of the global war on terrorism since 2001, many USAF fighter pilots who were formerly physically flying USAF aircraft such as the F-16 were tasked with sitting in a cargo container and staring at a screen, while their inputs to controls were beamed across the world at the speed of light to the controlled drone, which was often loitering for hours over a target area that required persistent ISR. Several Hollywood movies (such as Good Kill (2014)) have been made about this twofold life of USAF pilots. Did the USAF not know that these circumstances would erode morale? Do they know why pilots sign up for service, and why they stay?

How About Battlefield Networking?

In previous posts in this blog, we’ve seen that information is a critical resource. The ability to share information on a battlefield network is the defining capability about how we will win future wars, according to Deputy Defense Secretary Robert Work. Most units in the USAF (as well as most NATO units) have the Link 16 network (depicted in blue above). This was conceived in 1967 by MITRE, demonstrated in 1973 by MITRE, and developed as the Joint Tactical Information Distribution System (JTIDS) in 1981 by what is now BAE Systems. “Fielding proceeded slowly throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s with rapid expansion (following 9/11) in preparation for Operation Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan) and Operation Iraqi Freedom.”

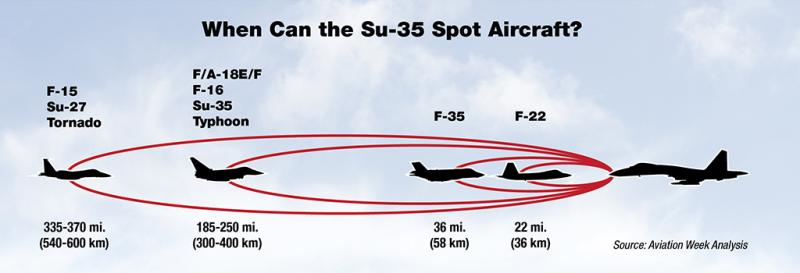

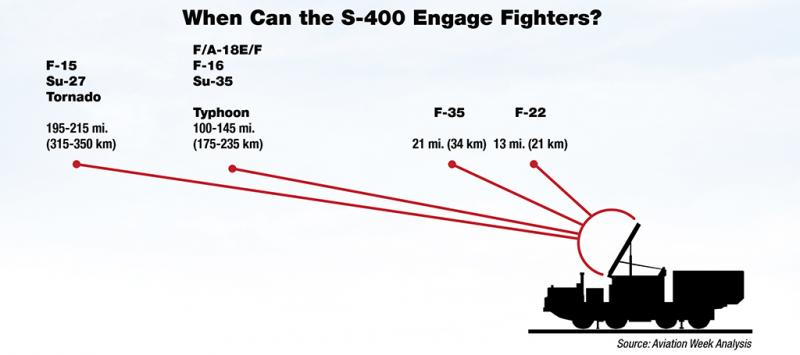

Not all units are equipped with Link 16 capability, especially the new stealth fighters, since broadcasting over this network gives away a units position. Instead, the F-22 was equipped with the In-Flight Data Link (IFDL), the red lines in diagram above. Since only the F-22 was equipped with this type of data link, legacy fighters like the F-15C could not communicate easily with F-22 units. Similarly, the F-35 program is being deployed with its own, the Multi-Function Advanced Data Link (MADL), which likewise preserves stealth, but also impedes communications with units not so equipped.

The difficulty and complexity of fielding a battlefield network which allows aircraft to communicate without compromising their stealth is tough, which is why Lt Col Berke stated that “these networks have yet to be created.” The Talon HATE pod is a stopgap capability, requested by the Pacific Air Forces, prototyped and deployed by Boeing Phantom Works. “With the stealthy F-22 buy truncated at 183 aircraft and F-35s being introduced into service far more slowly than planned, the Air Force is being forced to devise a connectivity regimen among these platforms to maximize their capabilities in battle.” The Talon HATE pod also includes an IRST, which the USAF has learned is effective at detecting stealth fighters.

Indeed, as reported by Aviation Week, the USAF is still in the process to rolling out Link 16 to its older tankers the KC-135, which are among the oldest aircraft still flown by the USAF. Perhaps this is a reaction to the Chinese operationalized stealth fighter, the J-20. It has recently been photographed carrying four external fuel tanks, which may give it the range to attack potentially vulnerable targets, such as tankers.