[The article below is reprinted from the August 1997 edition of The International TNDM Newsletter.]

Technology and the Human Factor in War

by Trevor N. Dupuy

The Debate

It has become evident to many military theorists that technology has become increasingly important in war. In fact (even though many soldiers would not like to admit it) most such theorists believe that technology has actually reduced the significance of the human factor in war, In other words, the more advanced our military technology, these “technocrats” believe, the less we need to worry about the professional capability and competence of generals, admirals, soldiers, sailors, and airmen.

The technocrats believe that the results of the Kuwait, or Gulf, War of 1991 have confirmed their conviction. They cite the contribution to those results of the U.N. (mainly U.S.) command of the air, stealth aircraft, sophisticated guided missiles, and general electronic superiority, They believe that it was technology which simply made irrelevant the recent combat experience of the Iraqis in their long war with Iran.

Yet there are a few humanist military theorists who believe that the technocrats have totally misread the lessons of this century‘s wars! They agree that, while technology was important in the overwhelming U.N. victory, the principal reason for the tremendous margin of U.N. superiority was the better training, skill, and dedication of U.N. forces (again, mainly U.S.).

And so the debate rests. Both sides believe that the result of the Kuwait War favors their point of view, Nevertheless, an objective assessment of the literature in professional military journals, of doctrinal trends in the U.S. services, and (above all) of trends in the U.S. defense budget, suggest that the technocrats have stronger arguments than the humanists—or at least have been more convincing in presenting their arguments.

I suggest, however, that a completely impartial comparison of the Kuwait War results with those of other recent wars, and with some of the phenomena of World War II, shows that the humanists should not yet concede the debate.

I am a humanist, who is also convinced that technology is as important today in war as it ever was (and it has always been important), and that any national or military leader who neglects military technology does so to his peril and that of his country, But, paradoxically, perhaps to an extent even greater than ever before, the quality of military men is what wins wars and preserves nations.

To elevate the debate beyond generalities, and demonstrate convincingly that the human factor is at least as important as technology in war, I shall review eight instances in this past century when a military force has been successful because of the quality if its people, even though the other side was at least equal or superior in the technological sophistication of its weapons. The examples I shall use are:

- Germany vs. the USSR in World War II

- Germany vs. the West in World War II

- Israel vs. Arabs in 1948, 1956, 1967, 1973 and 1982

- The Vietnam War, 1965-1973

- Britain vs. Argentina in the Falklands 1982

- South Africans vs. Angolans and Cubans, 1987-88

- The U.S. vs. Iraq, 1991

The demonstration will be based upon a marshaling of historical facts, then analyzing those facts by means of a little simple arithmetic.

Relative Combat Effectiveness Value (CEV)

The purpose of the arithmetic is to calculate relative combat effectiveness values (CEVs) of two opposing military forces. Let me digress to set up the arithmetic. Although some people who hail from south of the Mason-Dixon Line may be reluctant to accept the fact, statistics prove that the fighting quality of Northern soldiers and Southern soldiers was virtually equal in the American Civil War. (I invite those who might disagree to look at Livermore’s Numbers and Losses in the Civil War). That assumption of equality of the opposing troop quality in the Civil War enables me to assert that the successful side in every important battle in the Civil War was successful either because of numerical superiority or superior generalship. Three of Lee’s battles make the point:

- Despite being outnumbered, Lee won at Antietam. (Though Antietam is sometimes claimed as a Union victory, Lee, the defender, held the battlefield; McClellan, the attacker, was repulsed.) The main reason for Lee’s success was that on a scale of leadership his generalship was worth 10, while McClellan was barely a 6.

- Despite being outnumbered, Lee won at Chancellorsville because he was a 10 to Hooker’s 5.

- Lee lost at Gettysburg mainly because he was outnumbered. Also relevant: Meade did not lose his nerve (like McClellan and Hooker) with generalship worth 8 to match Lee’s 8.

Let me use Antietam to show the arithmetic involved in those simple analyses of a rather complex subject:

The numerical strength of McClellan’s army was 89,000; Lee’s army was only 39,000 strong, but had the multiplier benefit of defensive posture. This enables us to calculate the theoretical combat power ratio of the Union Army to the Confederate Army as 1.4:1.0. In other words, with substantial preponderance of force, the Union Army should have been successful. (The combat power ratio of Confederates to Northerners, of course, was the reciprocal, or 0.71:1.04)

However, Lee held the battlefield, and a calculation of the actual combat power ratio of the two sides (based on accomplishment of mission, gaining or holding ground, and casualties) was a scant, but clear cut: 1.16:1.0 in favor of the Confederates. A ratio of the actual combat power ratio of the Confederate/Union armies (1.16) to their theoretical combat power (0.71) gives us a value of 1.63. This is the relative combat effectiveness of the Lee’s army to McClellan’s army on that bloody day. But, if we agree that the quality of the troops was the same, then the differential must essentially be in the quality of the opposing generals. Thus, Lee was a 10 to McClellan‘s 6.

The simple arithmetic equation[1] on which the above analysis was based is as follows:

CEV = (R/R)/(P/P)

When:

CEV is relative Combat Effectiveness Value

R/R is the actual combat power ratio

P/P is the theoretical combat power ratio.

At Antietam the equation was: 1.63 = 1.16/0.71.

We’ll be revisiting that equation in connection with each of our examples of the relative importance of technology and human factors.

Air Power and Technology

However, one more digression is required before we look at the examples. Air power was important in all eight of the 20th Century examples listed above. Offhand it would seem that the exercise of air superiority by one side or the other is a manifestation of technological superiority. Nevertheless, there are a few examples of an air force gaining air superiority with equivalent, or even inferior aircraft (in quality or numbers) because of the skill of the pilots.

However, the instances of such a phenomenon are rare. It can be safely asserted that, in the examples used in the following comparisons, the ability to exercise air superiority was essentially a technological superiority (even though in some instances it was magnified by human quality superiority). The one possible exception might be the Eastern Front in World War II, where a slight German technological superiority in the air was offset by larger numbers of Soviet aircraft, thanks in large part to Lend-Lease assistance from the United States and Great Britain.

The Battle of Kursk, 5-18 July, 1943

Following the surrender of the German Sixth Army at Stalingrad, on 2 February, 1943, the Soviets mounted a major winter offensive in south-central Russia and Ukraine which reconquered large areas which the Germans had overrun in 1941 and 1942. A brilliant counteroffensive by German Marshal Erich von Manstein‘s Army Group South halted the Soviet advance, and recaptured the city of Kharkov in mid-March. The end of these operations left the Soviets holding a huge bulge, or salient, jutting westward around the Russian city of Kursk, northwest of Kharkov.

The Germans promptly prepared a new offensive to cut off the Kursk salient, The Soviets energetically built field fortifications to defend the salient against expected German attacks. The German plan was for simultaneous offensives against the northern and southern shoulders of the base of the Kursk salient, Field Marshal Gunther von K1uge’s Army Group Center, would drive south from the vicinity of Orel, while Manstein’s Army Group South pushed north from the Kharkov area, The offensive was originally scheduled for early May, but postponements by Hitler, to equip his forces with new tanks, delayed the operation for two months, The Soviets took advantage of the delays to further improve their already formidable defenses.

The German attacks finally began on 5 July. In the north General Walter Model’s German Ninth Army was soon halted by Marshal Konstantin Rokossovski’s Army Group Center. In the south, however, German General Hermann Hoth’s Fourth Panzer Army and a provisional army commanded by General Werner Kempf, were more successful against the Voronezh Army Group of General Nikolai Vatutin. For more than a week the XLVIII Panzer Corps advanced steadily toward Oboyan and Kursk through the most heavily fortified region since the Western Front of 1918. While the Germans suffered severe casualties, they inflicted horrible losses on the defending Soviets. Advancing similarly further east, the II SS Panzer Corps, in the largest tank battle in history, repulsed a vigorous Soviet armored counterattack at Prokhorovka on July 12-13, but was unable to continue to advance.

The principal reason for the German halt was the fact that the Soviets had thrown into the battle General Ivan Konev’s Steppe Army Group, which had been in reserve. The exhausted, heavily outnumbered Germans had no comparable reserves to commit to reinvigorate their offensive.

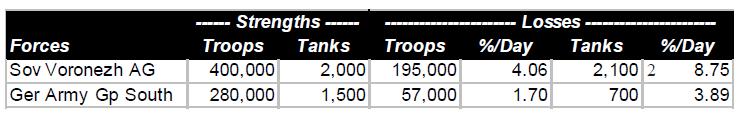

A comparison of forces and losses of the Soviet Voronezh Army Group and German Army Group South on the south face of the Kursk Salient is shown below. The strengths are averages over the 12 days of the battle, taking into consideration initial strengths, losses, and reinforcements.

A comparison of the casualty tradeoff can be found by dividing Soviet casualties by German strength, and German losses by Soviet strength. On that basis, 100 Germans inflicted 5.8 casualties per day on the Soviets, while 100 Soviets inflicted 1.2 casualties per day on the Germans, a tradeoff of 4.9 to 1.0

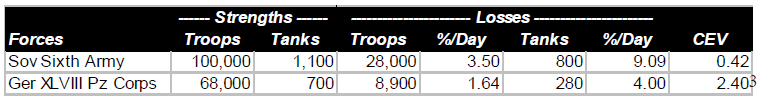

The statistics for the 8-day offensive of the German XLVIII Panzer Corps toward Oboyan are shown below. Also shown is the relative combat effectiveness value (CEV) of Germans and Soviets, as calculated by the TNDM. As was the case for the Battle of Antietam, this is derived from a mathematical comparison of the theoretical combat power ratio of the two forces (simply considering numbers and weapons characteristics), and the actual combat power ratios reflected by the battle results:

The statistics for the 8-day offensive of the German XLVIII Panzer Corps toward Oboyan are shown below. Also shown is the relative combat effectiveness value (CEV) of Germans and Soviets, as calculated by the TNDM. As was the case for the Battle of Antietam, this is derived from a mathematical comparison of the theoretical combat power ratio of the two forces (simply considering numbers and weapons characteristics), and the actual combat power ratios reflected by the battle results:

The calculated CEVs suggest that 100 German troops were the combat equivalent of 240 Soviet troops, comparably equipped. The casualty tradeoff in this battle shows that 100 Germans inflicted 5.15 casualties per day on the Soviets, while 100 Soviets inflicted 1.11 casualties per day on the Germans, a tradeoff of4.64. It is a rule of thumb that the casualty tradeoff is usually about the square of the CEV.

The calculated CEVs suggest that 100 German troops were the combat equivalent of 240 Soviet troops, comparably equipped. The casualty tradeoff in this battle shows that 100 Germans inflicted 5.15 casualties per day on the Soviets, while 100 Soviets inflicted 1.11 casualties per day on the Germans, a tradeoff of4.64. It is a rule of thumb that the casualty tradeoff is usually about the square of the CEV.

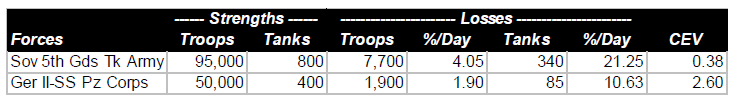

A similar comparison can be made of the two-day battle of Prokhorovka. Soviet accounts of that battle have claimed this as a great victory by the Soviet Fifth Guards Tank Army over the German II SS Panzer Corps. In fact, since the German advance was halted, the outcome was close to a draw, but with the advantage clearly in favor of the Germans.

The casualty tradeoff shows that 100 Germans inflicted 7.7 casualties per on the Soviets, while 100 Soviets inflicted 1.0 casualties per day on the Germans, for a tradeoff value of 7.7.

The casualty tradeoff shows that 100 Germans inflicted 7.7 casualties per on the Soviets, while 100 Soviets inflicted 1.0 casualties per day on the Germans, for a tradeoff value of 7.7.

When the German offensive began, they had a slight degree of local air superiority. This was soon reversed by German and Soviet shifts of air elements, and during most of the offensive, the Soviets had a slender margin of air superiority. In terms of technology, the Germans probably had a slight overall advantage. However, the Soviets had more tanks and, furthermore, their T-34 was superior to any tank the Germans had available at the time. The CEV calculations demonstrate that the Germans had a great qualitative superiority over the Russians, despite near-equality in technology, and despite Soviet air superiority. The Germans lost the battle, but only because they were overwhelmed by Soviet numbers.

German Performance, Western Europe, 1943-1945

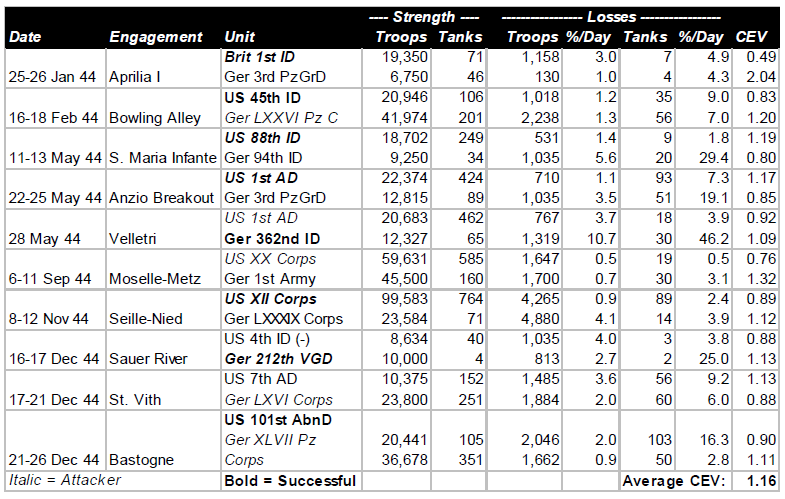

Beginning with operations between Salerno and Naples in September, 1943, through engagements in the closing days of the Battle of the Bulge in January, 1945, the pattern of German performance against the Western Allies was consistent. Some German units were better than others, and a few Allied units were as good as the best of the Germans. But on the average, German performance, as measured by CEV and casualty tradeoff, was better than the Western allies by a CEV factor averaging about 1.2, and a casualty tradeoff factor averaging about 1.5. Listed below are ten engagements from Italy and Northwest Europe during that 1944.

Technologically, German forces and those of the Western Allies were comparable. The Germans had a higher proportion of armored combat vehicles, and their best tanks were considerably better than the best American and British tanks, but the advantages were at least offset by the greater quantity of Allied armor, and greater sophistication of much of the Allied equipment. The Allies were increasingly able to achieve and maintain air superiority during this period of slightly less than two years.

Technologically, German forces and those of the Western Allies were comparable. The Germans had a higher proportion of armored combat vehicles, and their best tanks were considerably better than the best American and British tanks, but the advantages were at least offset by the greater quantity of Allied armor, and greater sophistication of much of the Allied equipment. The Allies were increasingly able to achieve and maintain air superiority during this period of slightly less than two years.

The combination of vast superiority in numbers of troops and equipment, and in increasing Allied air superiority, enabled the Allies to fight their way slowly up the Italian boot, and between June and December, 1944, to drive from the Normandy beaches to the frontier of Germany. Yet the presence or absence of Allied air support made little difference in terms of either CEVs or casualty tradeoff values. Despite the defeats inflicted on them by the numerically superior Allies during the latter part of 1944, in December the Germans were able to mount a major offensive that nearly destroyed an American army corps, and threatened to drive at least a portion of the Allied armies into the sea.

Clearly, in their battles against the Soviets and the Western Allies, the Germans demonstrated that quality of combat troops was able consistently to overcome Allied technological and air superiority. It was Allied numbers, not technology, that defeated the quantitatively superior Germans.

The Six-Day War, 1967

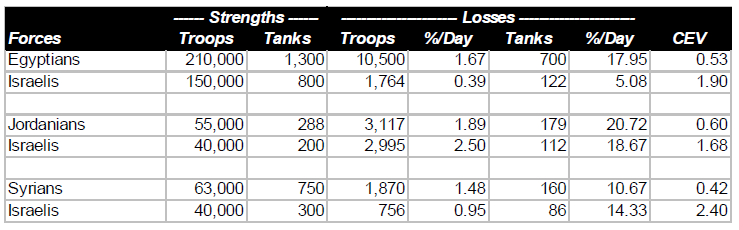

The remarkable Israeli victories over far more numerous Arab opponents—Egyptian, Jordanian, and Syrian—in June, 1967 revealed an Israeli combat superiority that had not been suspected in the United States, the Soviet Union or Western Europe. This superiority was equally awesome on the ground as in the air. (By beginning the war with a surprise attack which almost wiped out the Egyptian Air Force, the Israelis avoided a serious contest with the one Arab air force large enough, and possibly effective enough, to challenge them.) The results of the three brief campaigns are summarized in the table below:

It should be noted that some Israelis who fought against the Egyptians and Jordanians also fought against the Syrians. Thus, the overall Arab numerical superiority was greater than would be suggested by adding the above strength figures, and was approximately 328,000 to 200,000.

It should be noted that some Israelis who fought against the Egyptians and Jordanians also fought against the Syrians. Thus, the overall Arab numerical superiority was greater than would be suggested by adding the above strength figures, and was approximately 328,000 to 200,000.

It should also be noted that the technological sophistication of the Israeli and Arab ground forces was comparable. The only significant technological advantage of the Israelis was their unchallenged command of the air. (In terms of battle outcomes, it was irrelevant how they had achieved air superiority.) In fact this was a very significant advantage, the full import of which would not be realized until the next Arab-Israeli war.

The results of the Six Day War do not provide an unequivocal basis for determining the relative importance of human factors and technological superiority (as evidenced in the air). Clearly a major factor in the Israeli victories was the superior performance of their ground forces due mainly to human factors. At least as important in those victories was Israeli command of the air, in which both technology and human factors both played a part.

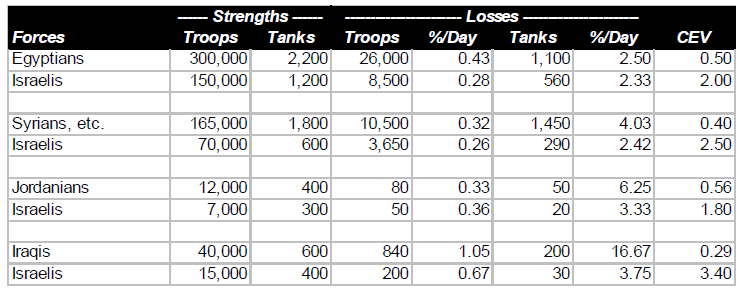

The October War, 1973

A better basis for comparing the relative importance of human factors and technology is provided by the results of the October War of 1973 (known to Arabs as the War of Ramadan, and to Israelis as the Yom Kippur War). In this war the Israeli unquestioned superiority in the air was largely offset by the Arabs possession of highly sophisticated Soviet air defense weapons.

One important lesson of this war was a reassessment of Israeli contempt for the fighting quality of Arab ground forces (which had stemmed from the ease with which they had won their ground victories in 1967). When Arab ground troops were protected from Israeli air superiority by their air defense weapons, they fought well and bravely, demonstrating that Israeli control of the air had been even more significant in 1967 than anyone had then recognized.

It should be noted that the total Arab (and Israeli) forces are those shown in the first two comparisons, above. A Jordanian brigade and two Iraqi divisions formed relatively minor elements of the forces under Syrian command (although their presence on the ground was significant in enabling the Syrians to maintain a defensive line when the Israelis threatened a breakthrough around 20 October). For the comparison of Jordanians and Iraqis the total strength is the total of the forces in the battles (two each) on which these comparisons are based.

It should be noted that the total Arab (and Israeli) forces are those shown in the first two comparisons, above. A Jordanian brigade and two Iraqi divisions formed relatively minor elements of the forces under Syrian command (although their presence on the ground was significant in enabling the Syrians to maintain a defensive line when the Israelis threatened a breakthrough around 20 October). For the comparison of Jordanians and Iraqis the total strength is the total of the forces in the battles (two each) on which these comparisons are based.

One other thing to note is how the Israelis, possibly unconsciously, confirmed that validity of their CEVs with respect to Egyptians and Syrians by the numerical strengths of their deployments to the two fronts. Since the war ended up in a virtual stalemate on both fronts, the overall strength figures suggest rough equivalence of combat capability.

The CEV values shown in the above table are very significant in relation to the debate about human factors and technology, There was little if anything to choose between the technological sophistication of the two sides. The Arabs had more tanks than the Israelis, but (as Israeli General Avraham Adan once told the author) there was little difference in the quality of the tanks. The Israelis again had command of the air, but this was neutralized immediately over the battlefields by the Soviet air defense equipment effectively manned by the Arabs. Thus, while technology was of the utmost importance to both sides, enabling each side to prevent the enemy from gaining a significant advantage, the true determinant of battlefield outcomes was the fighting quality of the troops, And, while the Arabs fought bravely, the Israelis fought much more effectively. Human factors made the difference.

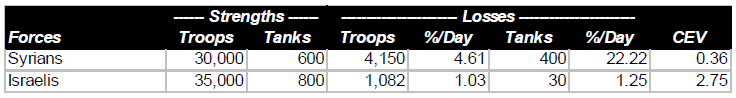

Israeli Invasion of Lebanon, 1982

In terms of the debate about the relative importance of human factors and technology, there are two significant aspects to this small war, in which Syrians forces and PLO guerrillas were the Arab participants. In the first place, the Israelis showed that their air technology was superior to the Syrian air defense technology, As a result, they regained complete control of the skies over the battlefields. Secondly, it provides an opportunity to include a highly relevant quotation.

The statistical comparison shows the results of the two major battles fought between Syrians and Israelis:

In assessing the above statistics, a quotation from the Israeli Chief of Staff, General Rafael Eytan, is relevant.

In assessing the above statistics, a quotation from the Israeli Chief of Staff, General Rafael Eytan, is relevant.

In late 1982 a group of retired American generals visited Israel and the battlefields in Lebanon. Just before they left for home, they had a meeting with General Eytan. One of the American generals asked Eytan the following question: “Since the Syrians were equipped with Soviet weapons, and your troops were equipped with American (or American-type) weapons, isn’t the overwhelming Israeli victory an indication of the superiority of American weapons technology over Soviet weapons technology?”

Eytan’s reply was classic: “If we had had their weapons, and they had had ours, the result would have been absolutely the same.”

One need not question how the Israeli Chief of Staff assessed the relative importance of the technology and human factors.

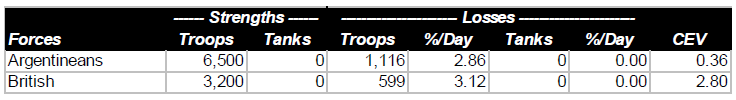

Falkland Islands War, 1982

It is difficult to get reliable data on the Falkland Islands War of 1982. Furthermore, the author of this article had not undertaken the kind of detailed analysis of such data as is available. However, it is evident from the information that is available about that war that its results were consistent with those of the other examples examined in this article.

The total strength of Argentine forces in the Falklands at the time of the British counter-invasion was slightly more than 13,000. The British appear to have landed close to 6,400 troops, although it may have been fewer. In any event, it is evident that not more than 50% of the total forces available to both sides were actually committed to battle. The Argentine surrender came 27 days after the British landings, but there were probably no more than six days of actual combat. During these battles the British performed admirably, the Argentinians performed miserably. (Save for their Air Force, which seems to have fought with considerable gallantry and effectiveness, at the extreme limit of its range.) The British CEV in ground combat was probably between 2.5 and 4.0. The statistics were at least close to those presented below:

It is evident from published sources that the British had no technological advantage over the Argentinians; thus the one-sided results of the ground battles were due entirely to British skill (derived from training and doctrine) and determination.

It is evident from published sources that the British had no technological advantage over the Argentinians; thus the one-sided results of the ground battles were due entirely to British skill (derived from training and doctrine) and determination.

South African Operations in Angola, 1987-1988

Neither the political reasons for, nor political results of, the South African military interventions in Angola in the 1970s, and again in the late 1980s, need concern us in our consideration of the relative significance of technology and of human factors. The combat results of those interventions, particularly in 1987-1988 are, however, very relevant.

The operations between elements of the South African Defense Force (SADF) and forces of the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (FAPLA) took place in southeast Angola, generally in the region east of the city of Cuito-Cuanavale. Operating with the SADF units were a few small units of Jonas Savimbi’s National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA). To provide air support to the SADF and UNITA ground forces, it would have been necessary for the South Africans to establish air bases either in Botswana, Southwest Africa (Namibia), or in Angola itself. For reasons that were largely political, they decided not to do that, and thus operated under conditions of FAPLA air supremacy. This led them, despite terrain generally unsuited for armored warfare, to use a high proportion of armored vehicles (mostly light armored cars) to provide their ground troops with some protection from air attack.

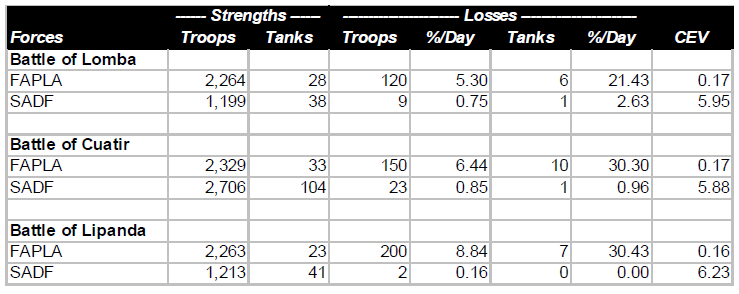

Summarized below are the results of three battles east of Cuito-Cuanavale in late 1987 and early 1988. Included with FAPLA forces are a few Cubans (mostly in armored units); included with the SADF forces are a few UNITA units (all infantry).

FAPLA had complete command of air, and substantial numbers of MiG-21 and MiG-23 sorties were flown against the South Africans in all of these battles. This technological superiority was probably partly offset by greater South African EW (electronic warfare) capability. The ability of the South Africans to operate effectively despite hostile air superiority was reminiscent of that of the Germans in World War II. It was a further demonstration that, no matter how important technology may be, the fighting quality of the troops is even more important.

FAPLA had complete command of air, and substantial numbers of MiG-21 and MiG-23 sorties were flown against the South Africans in all of these battles. This technological superiority was probably partly offset by greater South African EW (electronic warfare) capability. The ability of the South Africans to operate effectively despite hostile air superiority was reminiscent of that of the Germans in World War II. It was a further demonstration that, no matter how important technology may be, the fighting quality of the troops is even more important.

The tank figures include armored cars. In the first of the three battles considered, FAPLA had by far the more powerful and more numerous medium tanks (20 to 0). In the other two, SADF had a slight or significant advantage in medium tank numbers and quality. But it didn’t seem to make much difference in the outcomes.

Kuwait War, 1991

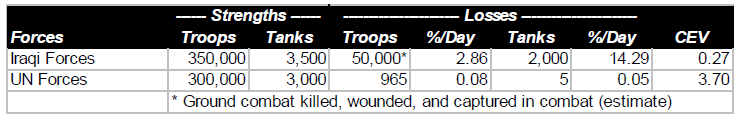

The previous seven examples permit us to examine the results of Kuwait (or Second Gulf) War with more objectivity than might otherwise have possible. First, let’s look at the statistics. Note that the comparison shown below is for four days of ground combat, February 24-28, and shows only operations of U.S. forces against the Iraqis.

There can be no question that the single most important contribution to the overwhelming victory of U.S. and other U.N. forces was the air war that preceded, and accompanied, the ground operations. But two comments are in order. The air war alone could not have forced the Iraqis to surrender. On the other hand, it is evident that, even without the air war, U.S. forces would have readily overwhelmed the Iraqis, probably in more than four days, and with more than 285 casualties. But the outcome would have been hardly less one-sided.

There can be no question that the single most important contribution to the overwhelming victory of U.S. and other U.N. forces was the air war that preceded, and accompanied, the ground operations. But two comments are in order. The air war alone could not have forced the Iraqis to surrender. On the other hand, it is evident that, even without the air war, U.S. forces would have readily overwhelmed the Iraqis, probably in more than four days, and with more than 285 casualties. But the outcome would have been hardly less one-sided.

The Vietnam War, 1965-1973

It is impossible to make the kind of mathematical analysis for the Vietnam War as has been done in the examples considered above. The reason is that we don’t have any good data on the Vietcong—North Vietnamese forces,

However, such quantitative analysis really isn’t necessary There can be no doubt that one of the opponents was a superpower, the most technologically advanced nation on earth, while the other side was what Lyndon Johnson called a “raggedy-ass little nation,” a typical representative of “the third world.“

Furthermore, even if we were able to make the analyses, they would very possibly be misinterpreted. It can be argued (possibly with some exaggeration) that the Americans won all of the battles. The detailed engagement analyses could only confirm this fact. Yet it is unquestionable that the United States, despite airpower and all other manifestations of technological superiority, lost the war. The human factor—as represented by the quality of American political (and to a lesser extent military) leadership on the one side, and the determination of the North Vietnamese on the other side—was responsible for this defeat.

Conclusion

In a recent article in the Armed Forces Journal International Col. Philip S. Neilinger, USAF, wrote: “Military operations are extremely difficult, if not impossible, for the side that doesn’t control the sky.” From what we have seen, this is only partly true. And while there can be no question that operations will always be difficult to some extent for the side that doesn’t control the sky, the degree of difficulty depends to a great degree upon the training and determination of the troops.

What we have seen above also enables us to view with a better perspective Colonel Neilinger’s subsequent quote from British Field Marshal Montgomery: “If we lose the war in the air, we lose the war and we lose it quickly.” That statement was true for Montgomery, and for the Allied troops in World War II. But it was emphatically not true for the Germans.

The examples we have seen from relatively recent wars, therefore, enable us to establish priorities on assuring readiness for war. It is without question important for us to equip our troops with weapons and other materiel which can match, or come close to matching, the technological quality of the opposition’s materiel. We must realize that we cannot—as some people seem to think—buy good forces, by technology alone. Even more important is to assure the fighting quality of the troops. That must be, by far, our first priority in peacetime budgets and in peacetime military activities of all sorts.

NOTES

[1] This calculation is automatic in analyses of historical battles by the Tactical Numerical Deterministic Model (TNDM).

[2] The initial tank strength of the Voronezh Army Group was about 1,100 tanks. About 3,000 additional Soviet tanks joined the battle between 6 and 12 July. At the end of the battle there were about 1,800 Soviet tanks operational in the battle area; at the same time there were about 1,000 German tanks still operational.

[3] The relative combat effectiveness value of each force is calculated in comparison to 1.0. Thus the CEV of the Germans is 2.40:1.0, while that of the Soviets is 0.42: 1.0. The opposing CEVs are always the reciprocals of each other.

The U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command has released a revised draft version of its

The U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command has released a revised draft version of its

In an

In an