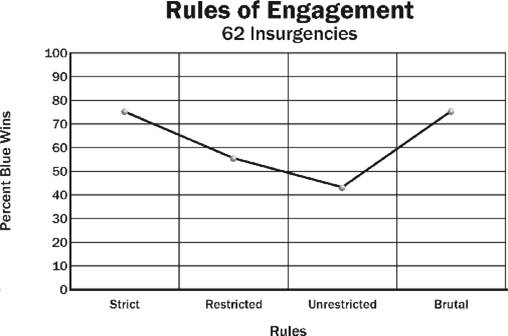

Does bombing create insurgents? This is an issue we have never examined. We did examine whether rules of engagements influenced the outcome of insurgencies, and we have a chapter on it in my book (Chapter 9: “Rules of Engagement and Measurements of Brutality,” America’s Modern Wars: Understanding Iraq, Afghanistan and Vietnam, pages 83-95). What we ended up with was a series of charts, not quite statistically significant, that showed that as rules of engagement became stricter the chance of a counterinsurgent victory (blue win) increased, rising from around 40% for “unrestricted” rules of engagements to around 75% for “strict” rules of engagement. While this was a pattern, we are not sure there is direct cause-and-effect here, although we suspect so. It also showed that the “brutal” approach also generated counterinsurgent victory around 75% of the time. A sample chart from the book is shown below:

But probably more immediately relevant to the discussion is the work we did on “General Level of Brutality” (pages 92-95). In that analysis, we compared the outcome, a counterinsurgent victory (blue win) vice an insurgent victory (red win), to civilians killed per 100,000 population. We examined this for 40 insurgencies from 1948 to the present (at the time it was 2009). What we showed was:

- Low civilian loss rates (less than 8.00 killed) results in 14% red wins (14 cases)

- Medium civilian loss rates (8.91 – 56.54) results in 38% red wins (21 cases)

- High civilian loss rates (115.54 – 624.16) results in 60% red wins (5 cases)

Or conversely:

- Low civilian loss rates (less than 8.00 killed) results in 79% blue wins (14 cases)

- Medium civilian loss rates (8.91 – 56.54) results in 43% blue wins (21 cases)

- High civilian loss rates (115.54 – 624.16) results in 20% blue wins (5 cases)

For the total of 40 cases, 33% result in red wins, 15% in “gray” outcome (ongoing or drawn), and 52% in a blue win. We put the data into a three-by-three matrix and tested it to Fisher’s exact test and obtained a two-sided p-value of 0.1135. For the non-statisticians, what this means is that there is an 89% chance that this relationship is not due to chance. When we remove the “gray” results from the table, then the two-sided p-value is 0.0576. This is even more significant. The data used is in the book if anyone wishes to go back and re-test or re-categorize it.

Our conclusions were:

“Therefore, we tentatively conclude that increased levels of brutality favor the insurgency when the number of civilians killed each year averages more than 9 per 100,000 in the population.”

We then expanded that conclusion:

“The inverse is that it is to the long-term advantage of counterinsurgent forces to limit damage to civilian populations, whether caused by their own or by insurgent actions. This means tightly controlled rules of engagement and probably requires a strictly limited use of artillery and airpower. It also means properly protecting the host population, which would probably require the deployment of significant security forces as part of a total counterinsurgent force.”

When one compares these results to the desire to add more ordnance to the effort to defeat ISIL, and the stated opinion by some that we should also target their families, then one wonders how effective such an air campaign will be. Will it really attrite and reduce an insurgency, or will the insurgency grow at the same or faster rate than they are attrited? This is clearly something that needs to be studied further (and analytically) before we make it a matter of policy. This is assuming that one is comfortable with the moral implications of such a policy.