There seems to be a sense out there that somehow or the other, that the Russians are very stolid, patient, long-suffering and willing to tolerate considerable duress under their government without complaint. Not sure exactly how that idea got established. The last hundred years of Russian history has shown considerable instability.

In the last hundred years Russia has had three revolutions that overthrew the leadership and changed the entire form of government. The first revolution happened with the “February Revolution” which occurred in March 1917, when the Tsar abdicated and a provisional government was established, headed first by Prince Georgii Lvov and then by Alexander Kerensky. This actually briefly created a struggling democratic government that ruled (or misruled) Russia for eight months. The next revolution was when the Bolsheviks bloodily throw that government out of power and took over in their “October Revolution” (which occurred in November under the new calendar). The third revolution occurred in December 1991 when the heads of Russia, Belarus and Ukraine decided that they would rule themselves and dismissed the communist government headed by Mikhail Gorbachev, dissolving the Soviet Union.

This is three successful revolutions in a hundred years, or one every 33 if you want to use an average. Of course, two occurred in an eight month period, and then it was 74 years before the next one occurred.

On the other hand, there have been some significant changes to the Russian governance that did not necessarily include large street protests. For example, the shift from Stalin to Khrushchev generated significant changes in how the country was run and managed. Communism under Khrushchev and its later leaders was very different from the leadership of Lenin or Stalin, when a communist society was being built, often with considerable brutality. It was a change from a state that was revolutionary to a more mature and stable dictatorship. It also introduced the idea of reform of the Soviet system, something that did not last long under Khruschchev, but would later influence Gorbachev.

The next significant change was the reform movement that started under Gorbachev in 1986 or was it Andropov in 1982? Gorbachev arrived in power in 1985, instituted “Perestroika” (restructuring) in 1986 “Glasnost” (openness) in 1988. These reforms were quickly followed by the ending of the Soviet Union in 1991, but it was a significant change in the governance of the Soviet Union for as long as it lasted.

Then there was another significant change in governance with the change from Yelstin to Putin in 2000. This moved the country from a troubled democracy to one that for all practical purposes over time has turned into a dictatorship.

The interesting aspect of all four of these last changes is their fundamentally peaceful nature. Three were done with little open protests and the collapse of the Soviet Union happened four months after the violence of the “August Coup.” Even though their impact was far reaching, they were hardly classic revolutions (unlike the two in 1917). They might be better described as reform movements or even palace coups, but they did significantly change the way the country was ruled. So, this is six major changes in how the country was ruled over a hundred year, or one every 17 years, with the longest being 37 years, being from the October Revolution in late 1917 to the demotion of Malenkov in early 1955 (who was eventually allowed to retire instead of being killed, which was a significant change in the Soviet system).

In contrast the United States has not had any revolutions in the last 100 years, and no significant changes in the way we are governed. The two biggest changes in our recent history was the “New Deal” package of reforms that came during the Great Depression of the 1930s and what I call our “cultural revolution” of the 1960s. They certainly were significant, hard to say if they were as significant as the three non-revolutionary changes in Russia. So, I would argue that Russia is more prone to revolution and revolutionary change than places like the United States, United Kingdom or many other modern democratic counties. This should not really be surprising.

But one more point about the “long-suffering” image of the Russian people. In World War I, Russia lost 1.1% of its population in the war and its government was overthrown (twice). In World War I, France lost 3.4% of its population while Britain & Ireland lost 1.6% (and Scotland lost 3.1%). Other countries that lost a higher percent of population killed than Russia are: Australia at 1.2%, New Zealand 1.5%, Italy 1.6%, Bulgaria 1.9%, Austria-Hungary 1.9%, Germany 3.0%, Rumania 3.3%, Turkey 3.7%, and poor Serbia at 5.7% of their population lost in World War I! (Just for comparison, the U.S. lost 0.1% of its population in World War I, see Niall Ferguson, Pity of War, page 299). The “long-suffering” Russia people seemed to have bailed out a little earlier and at less cost than most of the other major powers in World War I. As I also like to point out to people convinced of the softness of America and the firmness of the old Soviet Union, the U.S. lost 58,000 people after a 15 year commitment to Vietnam (1957 – 1973) and then withdrew. The Soviet Union lost 15,000 people after a 9 year commitment to Afghanistan (1979-1989) and then withdrew.

So, it would appear from a most casual look that there is not much of an argument that the Russian government is somehow or the other more immune to revolution or palace coups or other significant changes in ruling systems because of the “long-suffering” nature of the population. It appears that they are as willing as most to change things up and more willing than some.

Just to give one more number, Putin has been effectively in power for 16 years (since 2000).

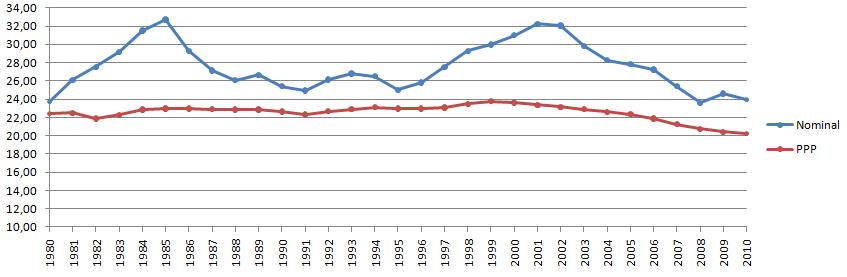

U.S. Share of World GDP (%) since 1980

U.S. Share of World GDP (%) since 1980