The weapon pictured above is the XM25 Counter Defilade Target Engagement (CDTE) precision-guided grenade launcher. According to its manufacturer, Orbital ATK,

The XM25 is a next-generation, semi-automatic weapon designed for effectiveness against enemies protected by walls, dug into foxholes or hidden in hard-to-reach places.

The XM25 provides the soldier with a 300 percent to 500 percent increase in hit probability to defeat point, area and defilade targets out to 500 meters. The weapon features revolutionary high-explosive, airburst ammunition programmed by the weapon’s target acquisition/fire control system.

Following field testing in Afghanistan that reportedly produced mixed results, the U.S. Army is seeking funding the Fiscal Year 2017 defense budget to acquire 105 of the weapons for issue to specifically-trained personnel at the tactical unit level.

The purported capabilities of the weapon have certainly raised expectations for its utility. A program manager in the Army’s Program Executive Office declared “The introduction of the XM25 is akin to other revolutionary systems such as the machine gun, the airplane and the tank, all of which changed battlefield tactics.” An industry observer concurred, claiming that “The weapon’s potential revolutionary impact on infantry tactics is undeniable.”

Well…maybe. There is little doubt that the availability of precision-guided standoff weapons at the squad or platoon level will afford significant tactical advantages. Whatever technical problems that currently exist will be addressed and there will surely be improvements and upgrades.

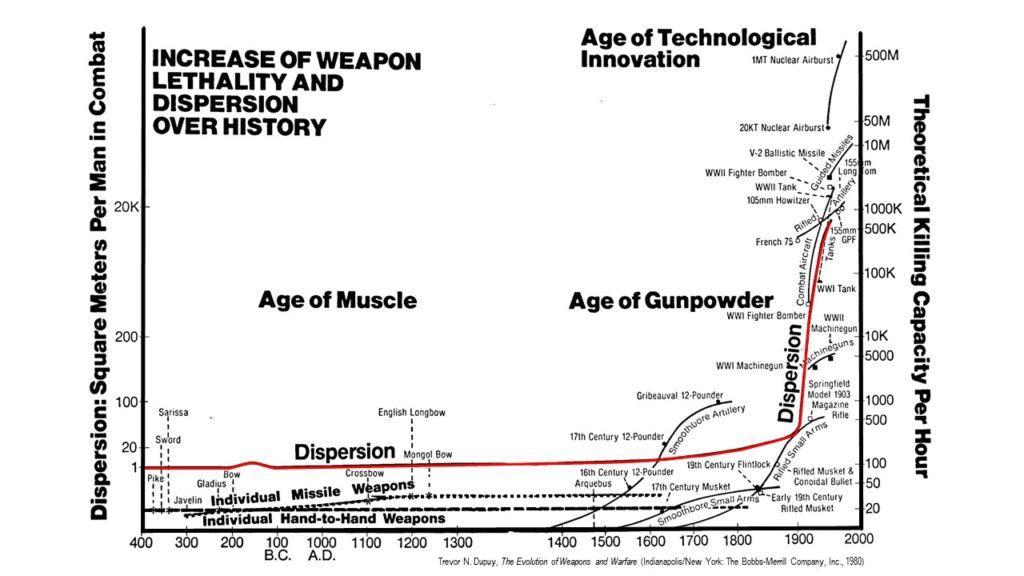

It seems unlikely, however, that the XM25 will bring revolutionary change to the battlefield. In his 1980 study The Evolution of Weapons and Warfare, Trevor N. Dupuy explored the ongoing historical relationship between technological change and adaptation on the battlefield. The introduction of increasingly lethal weapons has led to corresponding changes in the ways armies fight.

Assimilation of a significant increase in [weapon] lethality has generally been marked (a) by dispersion, thus reducing the number of people exposed to the new weapon in the enemy’s hands; (b) by giving greater freedom of maneuver; and (c) by improving cooperation among the different arms and services. [p. 337]

As the chart below illustrates (click for a larger version), as weapons have become more lethal over time, combat forces have adjusted by dispersing in greater frontage and depth on the battlefield (as reflected by the red line).

Dupuy noted that there is a lag between the introduction of a new weapon and its full integration into an army’s tactics and force structure.

In modern times — and to some extent in earlier eras — there has been an interval of approximately twenty years between introduction and assimilation of new weapons…it is significant that, despite the rising tempo of invention, this time lag remained relatively constant. [p. 338]

Moreover, Dupuy observed that true military revolutions are historically rare, and require more than technological change to occur.

Save for the recent significant exception of strategic nuclear weapons, there have been no historical instances in which new and more lethal weapons have, of themselves, altered the conduct of war or the balance of power until they have been incorporated into a new tactical system exploiting their lethality and permitting their coordination with other weapons. [p. 340]

Looking at the trends over time suggests that any resulting changes will be evolutionary rather than revolutionary. The ways armies historically have adapted to new weapons — dispersion, tactical flexibility, and combined arms —- are hallmarks of the fire and movement concept that is at the heart of modern combat tactics, which evolved in the early years of the 20th century, particularly during the First World War. However effective the XM25 may prove to be, it’s impact is unlikely to alter the basic elements of fire and movement tactics. Enemy combatants will likely adapt through even greater dispersion (the modern “empty battlefield“), tactical innovation, and combinations of countering weapons. It is also likely that it will take time, trial and error, and effective organizational leadership in order to take full advantage of the XM25’s capabilities.

[Edited]

Article in The National Interest by Michael Peck on Russia reconstituting the First Guards Tank Army:

Article in The National Interest by Michael Peck on Russia reconstituting the First Guards Tank Army: