When historian and pundit James Jay Carafano called for the U.S. defense community to refocus on the classic principles of war, he did not specify whose list should be adopted. A quick check reveals several such lists, some with vastly different concepts reflecting different national and temporal experiences.

When historian and pundit James Jay Carafano called for the U.S. defense community to refocus on the classic principles of war, he did not specify whose list should be adopted. A quick check reveals several such lists, some with vastly different concepts reflecting different national and temporal experiences.

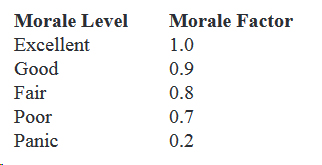

I suspect debates over the lists and each principle could very well spark a new academic sub-discipline. (Let the wild rumpus start!) Interestingly enough, Trevor N. Dupuy considered the 1954 edition of the U.S. Army’s Field Manual FM 100-5, Field Service Regulations, Operations to have the best official summary of the principles of war. That list is offered for consideration below:

Section I. PRINCIPLES OF WAR

- General

The principles of war are fundamental truths governing the prosecution of war. Their proper application is essential to the exercise of command and to successful conduct of military operations. The degree of application of any specific principle will vary with the situation and the application thereto of sound judgment and tactical sense.

- Objective

Every military operation must be directed toward a decisive, obtainable objective. The destruction of the enemy’s armed forces and his will to fight is the ultimate military objective of war. The objective of each operation must contribute to this ultimate objective. Each intermediate objective must be such that its attainment will most directly, quickly, and economically contribute to the purpose of the operation. It must permit the application of the maximum means available. Its selection must be based upon consideration of means available, the enemy, and the area of operations. Secondary objectives of any operation must contribute to the attainment of the principal objective.

- Offensive

Only offensive action achieves decisive results. Offensive action permits the commander to exploit the initiative and impose his will on the enemy. The defensive may be forced on the commander, but it should be deliberately adopted only as a temporary expedient while awaiting an opportunity for offensive action or for the purpose of economizing forces on a front where a decision is not sought. Even on the defensive the commander seeks every opportunity to seize the initiative and achieve decisive results by offensive action.

- Simplicity

Simplicity must be the keynote of military operations. Uncomplicated plans clearly expressed in orders promote common understanding and intelligent execution. Even the most simple plan is usually difficult to execute in combat. Simplicity must be applied to organization, methods, and means in order to produce orderliness on the battlefield.

- Unity of Command

The decisive application of full combat power requires unity of command. Unity of command obtains unity of effort by the coordinated action of all forces toward a common goal. Coordination may be achieved by direction or by cooperation. It is best achieved by vesting a single commander with requisite authority. Unity of effort is furthered by willing and intelligent cooperation among all elements of the forces involved. Pearl Harbor is an example of failure in organization for command. See appendix II.

- Mass

Maximum available combat power must be applied at the point of decision.Mass is the concentration of means at the critical time and place to the maximum degree permitted by the situation. Proper application of the principle of mass, in conjunction with the other principles of war, may permit numerically inferior forces to achieve decisive combat superiority. Mass is essentially a combination of manpower and firepower and is not dependent upon numbers alone; the effectiveness of mass may be increased by superior weapons, tactics, and morale.

- Economy of Force

Minimum essential means must be employed at points other than that of decision.To devote means to unnecessary secondary efforts or to employ excessive means on required secondary efforts is to violate the principle of both mass and the objective. Limited attacks, the defensive, deception, or even retrograde action are used in noncritical areas to achieve mass in the critical area.

- Maneuver

Maneuver must be used to alter the relative combat power of military forces.Maneuver is the positioning of forces to place the enemy at a relative disadvantage. Proper positioning of forces in relation to the enemy frequently can achieve results which otherwise could be achieved only at heavy cost in men and material. In many situations maneuver is made possible only by the effective employment of firepower.

- Surprise

Surprise may decisively shift the balance of combat power in favor of the commander who achieves it.It consists of striking the enemy when, where, or in a manner for which he is unprepared. It is not essential that the enemy be taken unaware but only that he becomes aware too late to react effectively. Surprise can be achieved by speed, secrecy, deception, by variation in means and methods, and by using seemingly impossible terrain: Mass is essential to the optimum exploitation of the principle of surprise.

- Security

Security is essential to the application of the other principles of war.It consists of those measures necessary to prevent surprise, avoid annoyance, preserve freedom of action, and deny to the enemy information of our forces. Security denies to the enemy and retains for the commander the ability to employ his forces most effectively.

[Field Manual (FM) 100-5, Field Service Regulations, Operations (Washington, D.C., Department of the Army, 1954), pp. 25-27]

A number of forecasts of potential U.S. casualties in a war to evict Iraqi forces from Kuwait appeared in the media in the autumn of 1990. The question of the human costs became a political issue for the administration of George H. W. Bush and influenced strategic and military decision-making.

A number of forecasts of potential U.S. casualties in a war to evict Iraqi forces from Kuwait appeared in the media in the autumn of 1990. The question of the human costs became a political issue for the administration of George H. W. Bush and influenced strategic and military decision-making.