From Chapter 14 (Section H) of America’s Modern Wars:

H. Bleeding an Insurgency to Death

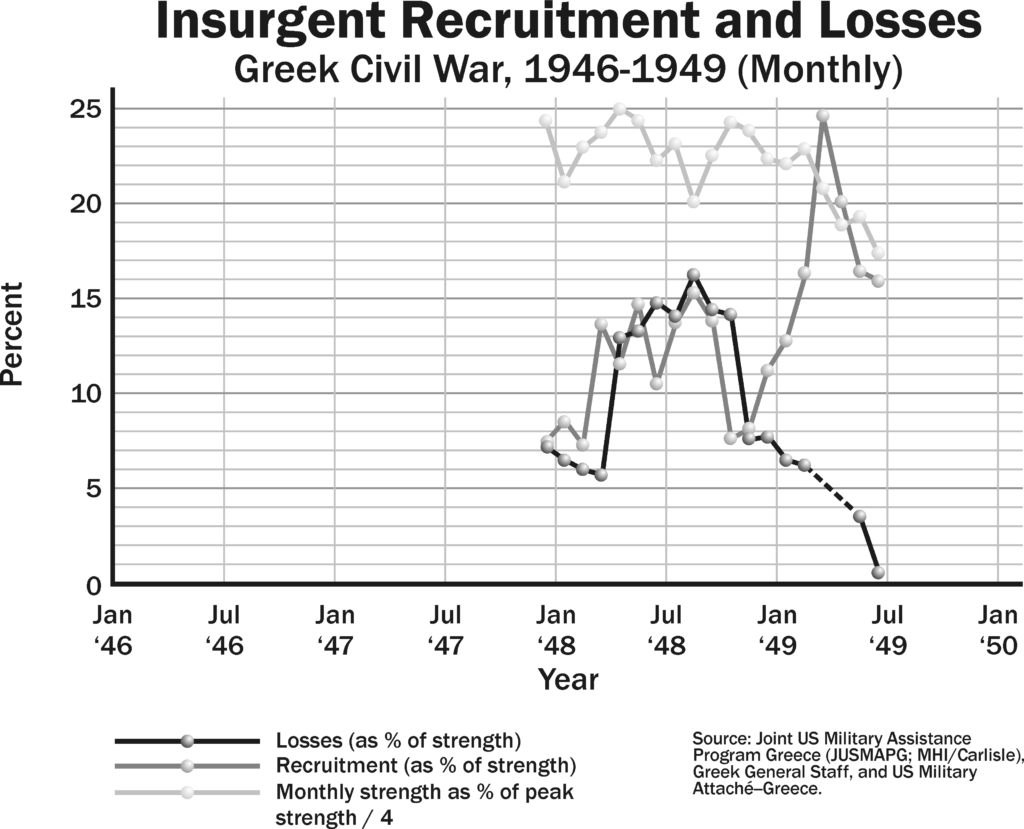

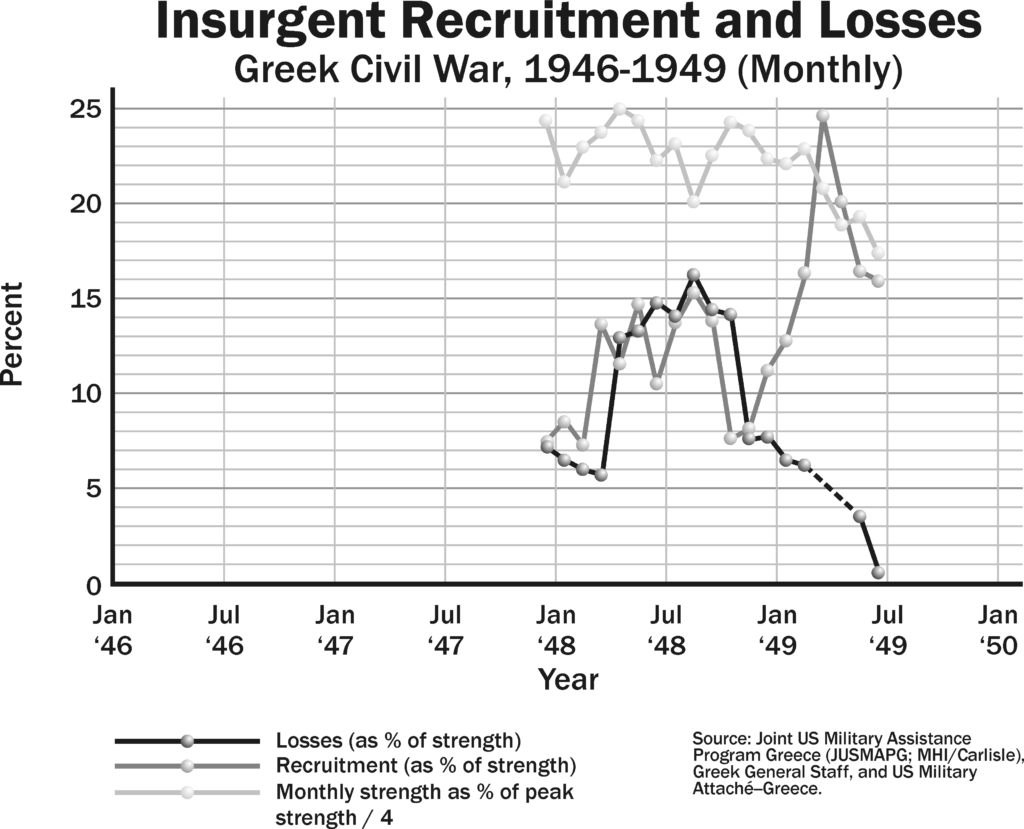

Bleeding an insurgency to death is possible, but rare. Let’s just look at a graph from the Greek Civil War:

This dramatic graph was created from a number of sources, all combined onto the same chart. The scale for monthly strength was divided by four fit them all together (meaning a figure of 25% for Monthly strength is actually 100% of strength). At the time, when I put the graph together, I intended it to illustrate the process where one could bleed an insurgency to death, by interrelating loss rates, exchange rates, recruitment, force strength, etc. When I presented this in a meeting in December 2004, I was then asked to look at tipping points.

It is difficult to bleed an insurgency to death. The problem is that only a small portion of the insurgents you are facing are active, full-time insurgents. So, mostly you are attriting the spearpoint. The part-time and casual insurgents tend to be active when they have a reason to, and tend to become inactive (and otherwise invisible) when the environment becomes too hot. As such, “search-and-destroy” missions and other such efforts tend to focus on the active people.

The problem is, as long as the rate of casualties among them is moderate, they can recruit and pull in new people. There is a base of support for insurgencies, and that base is a source of recruits. Unless one has shut down the recruiting source, then they can quickly replace the losses.

For example, let us say you have 10,000 insurgents, of which 2,000 are “full-time.” They are operating in a country with a population of one million. So we have the insurgency making up 1% of the population of the country. That is not out of line with historical cases. Let us say that 30% of the population favors the insurgency or are in areas under control of the insurgency.

Now, out of a population base of 300,000 civilians, one would expect to see about 3,000 new insurgents to come of age each year.[1] This means that the insurgents potentially have a new population of 3,000 coming-of-age boys each year to draw upon. Therefore, the counterinsurgents must grind through probably around 2,000 or more insurgents a year to actually be able to reduce insurgent strength from year to year. Otherwise, they get replaced as fast as they are being lost.

Expand this example to a country with 30,000 insurgents and 24 million population, like is potentially the case for Afghanistan and Iraq, and it is clear that bleeding the insurgency to death becomes almost an impossible proposition, no matter how long you stay.

Still, it was done in the case of the Greek Civil War. This was caused in part by a decision by the insurgents to increase the tempo of operations and go almost conventional. The result is that the insurgents conveniently choose to help the counterinsurgents bleed the insurgency to death. As can be seen, this quickly broke the back of the insurgency, and this occurred before Yugoslavia cut off support and bases for the insurgents. Basically, the insurgency was losing by fighting a traditional insurgency, so they changed their approach to increase the tempo of operations, and this simply sped up their eventual and inevitable defeat.

To some extent, the same thing happened in Vietnam with the Tet Offensive. Military, the offensive gutted the Viet Cong, and left them permanently weakened and less effective for the rest of the war. If the only force the U.S. was facing in Vietnam was the VC (Viet Cong), then this would have potentially led to a U.S. victory. The presence of a continued flow of forces from North Vietnam, including fully-armed combat regiments, compensated for the heavy losses the VC suffered.

Beyond those two cases, we do not have examples of insurgencies being bleed to death. The mathematics does not favor such an approach, although people invariably try it. One could describe General Westmoreland’s strategy in as Vietnam heavily oriented towards an attrition approach.

NOTES

[1] 300,000 divided by an average 50-year life span, divided by two to account for only males.