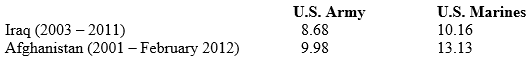

As the U.S. Army and the national security community seek a sense of what potential conflicts in the near future might be like, they see the distinct potential for large tank battles. Will technological advances change the character of armored warfare? Perhaps, but it seems more likely that the next big tank battles – if they occur – will likely resemble those from the past.

As the U.S. Army and the national security community seek a sense of what potential conflicts in the near future might be like, they see the distinct potential for large tank battles. Will technological advances change the character of armored warfare? Perhaps, but it seems more likely that the next big tank battles – if they occur – will likely resemble those from the past.

One aspect of future battle of great interest to military planners is probably going to tank loss rates in combat. In a previous post, I looked at the analysis done by Trevor Dupuy on the relationship between tank and personnel losses in the U.S. experience during World War II. Today, I will take a look at his analysis of historical tank loss rates.

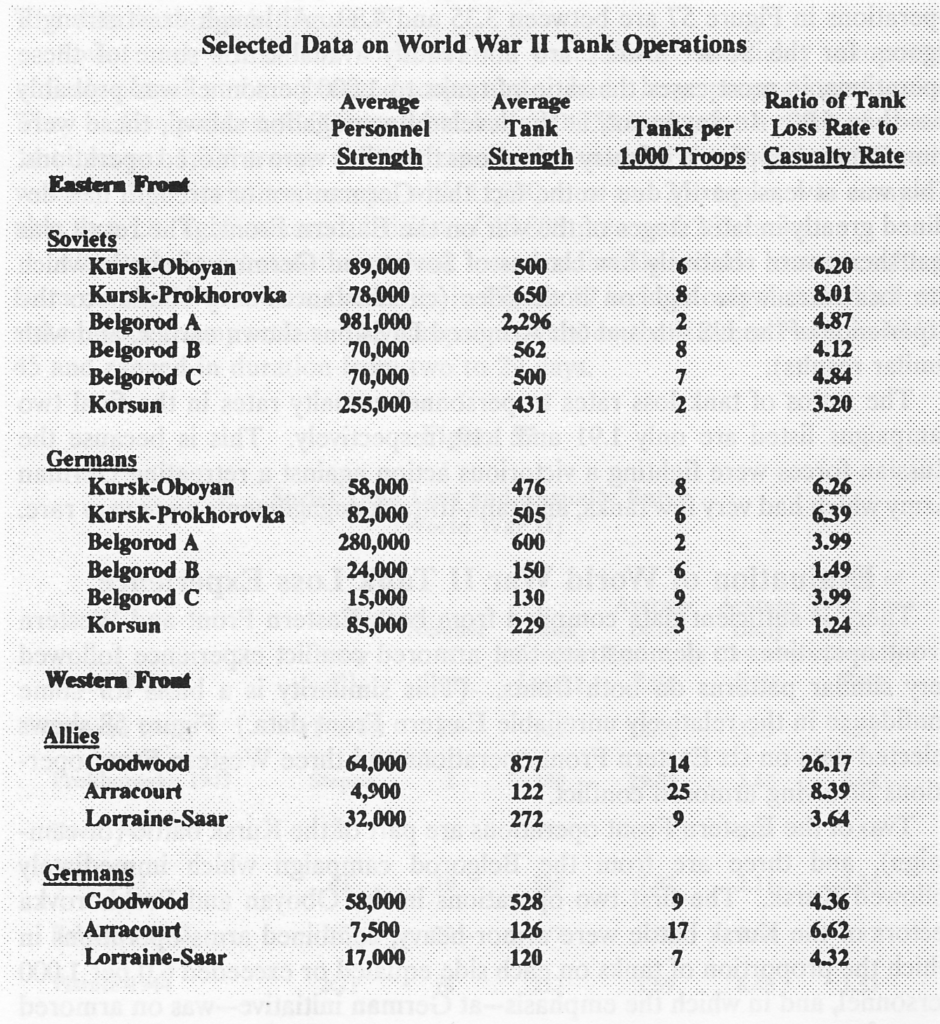

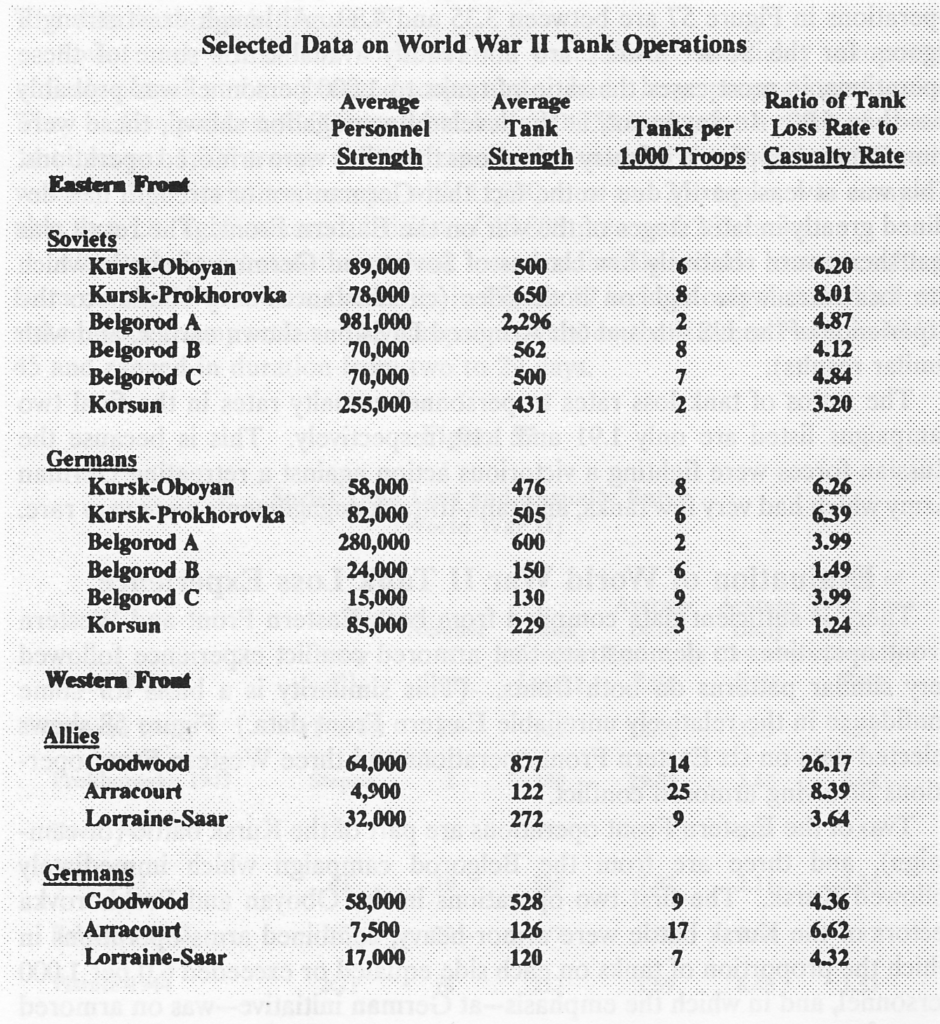

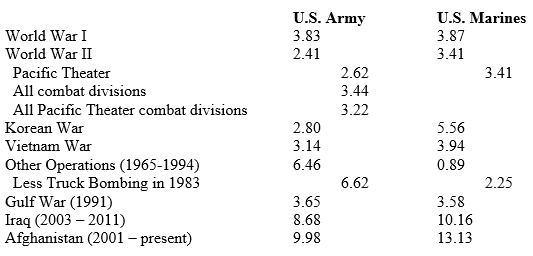

In general, Dupuy identified that a proportional relationship exists between personnel casualty rates in combat and losses in tanks, guns, trucks, and other equipment. (His combat attrition verities are discussed here.) Looking at World War II division and corps-level combat engagement data in 1943-1944 between U.S., British and German forces in the west, and German and Soviet forces in the east, Dupuy found similar patterns in tank loss rates.

In combat between two division/corps-sized, armor-heavy forces, Dupuy found that the tank loss rates were likely to be between five to seven times the personnel casualty rate for the winning side, and seven to 10 for the losing side. Additionally, defending units suffered lower loss rates than attackers; if an attacking force suffered a tank losses seven times the personnel rate, the defending forces tank losses would be around five times.

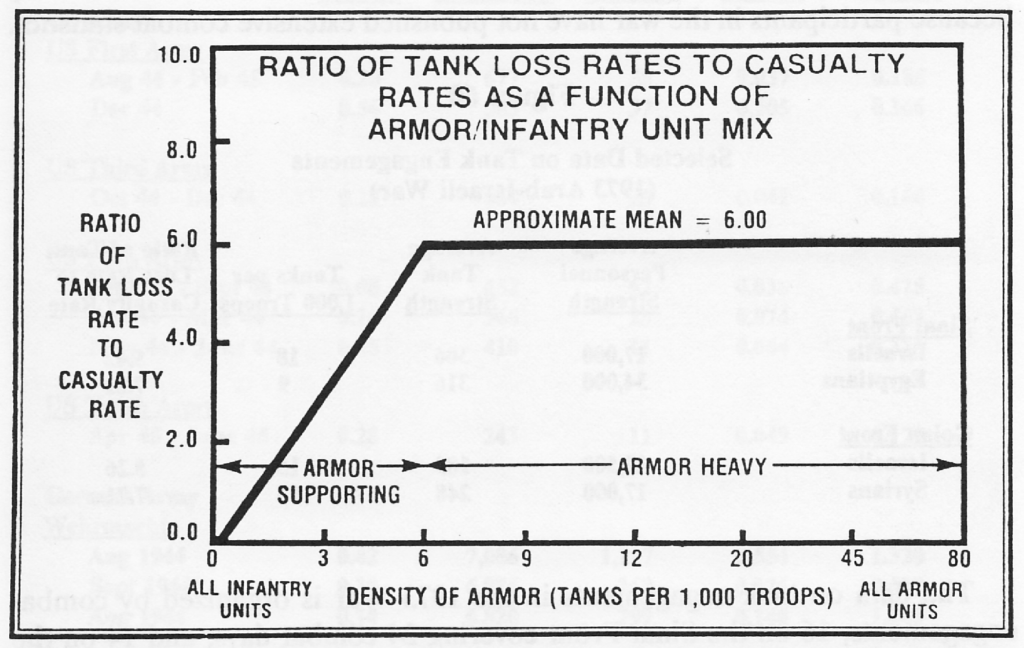

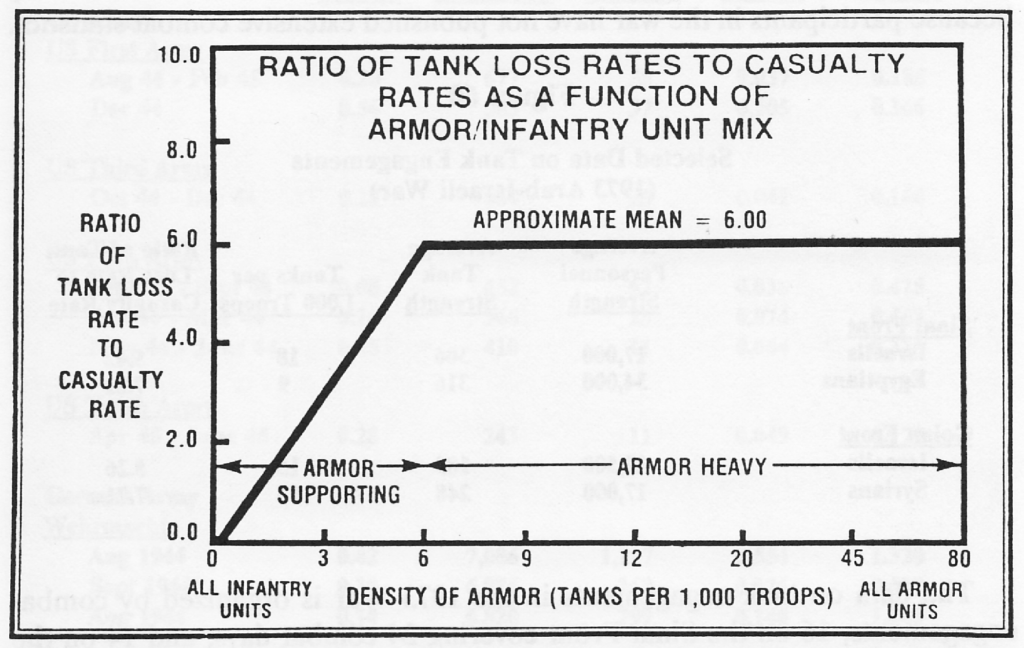

Dupuy also discovered the ratio of tank to personnel losses appeared to be a function of the proportion of tanks to infantry in a combat force. Units with fewer than six tanks per 1,000 troops could be considered armor supporting, while those with a density of more than six tanks per 1,000 troops were armor-heavy. Armor supporting units suffered lower tank casualty rates than armor heavy units.

Dupuy looked at tank loss rates in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War and found that they were consistent with World War II experience.

What does this tell us about possible tank losses in future combat? That is a very good question. One guess that is reasonably certain is that future tank battles will probably not involve forces of World War II division or corps size. The opposing forces will be brigade combat teams, or more likely, battalion-sized elements.

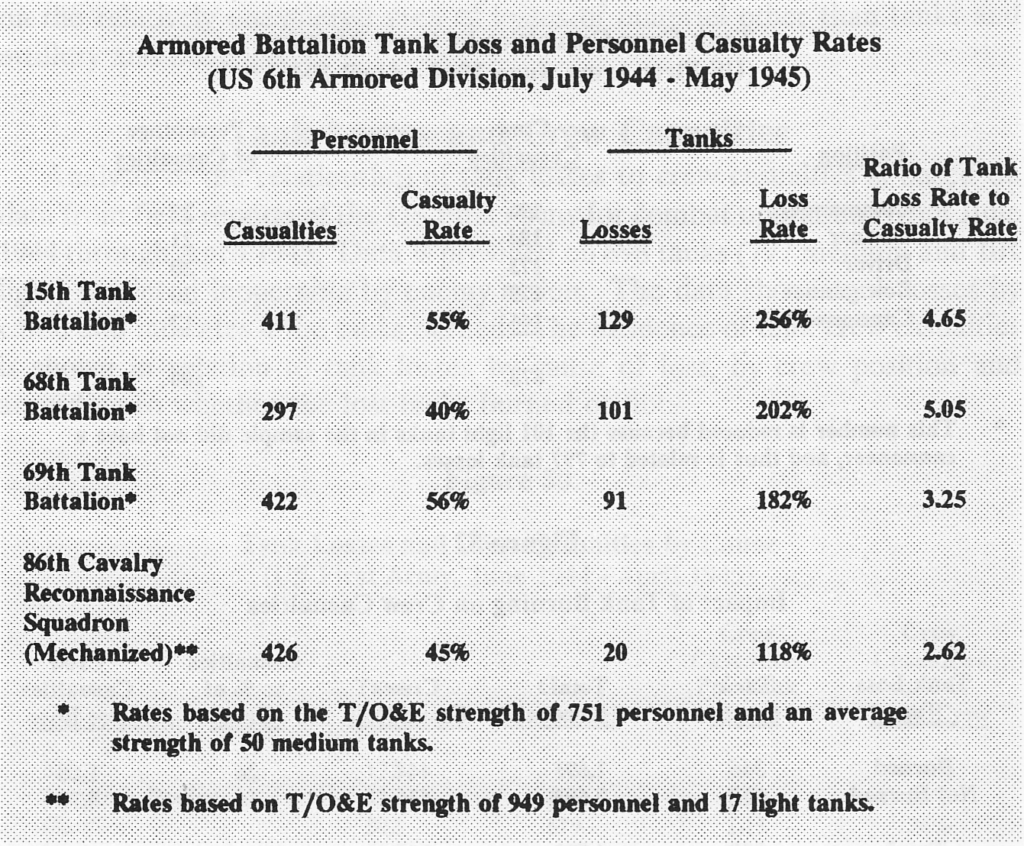

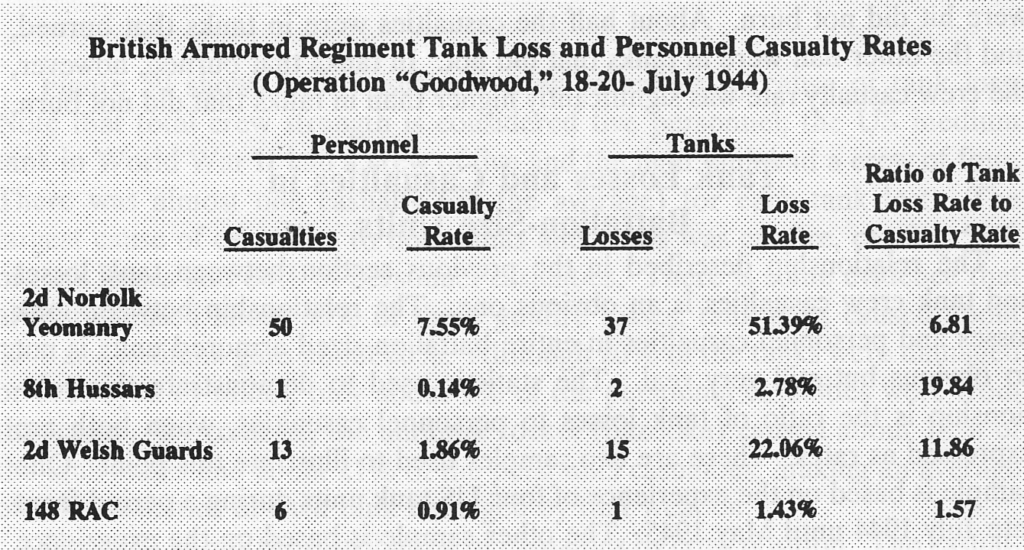

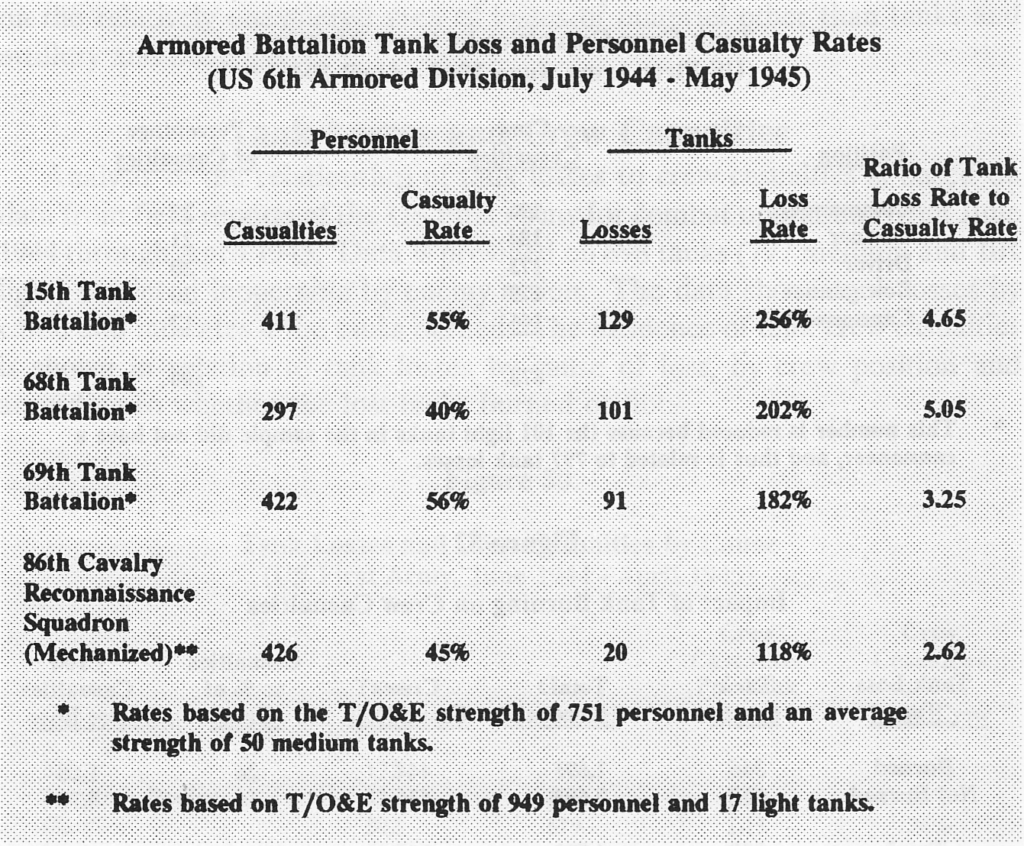

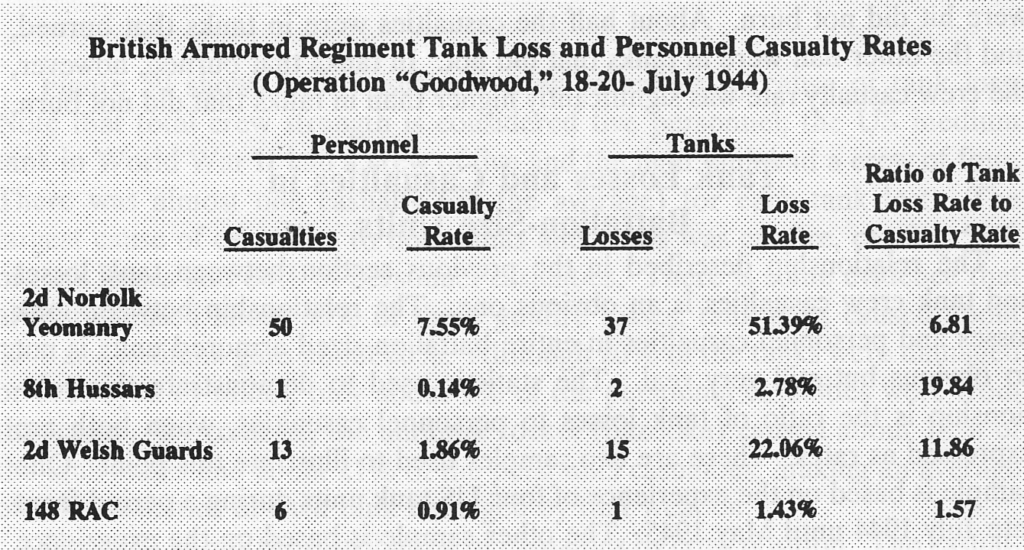

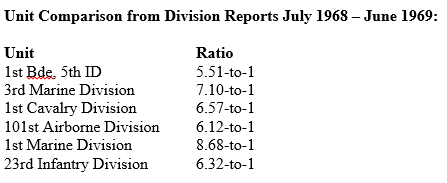

Dupuy did not have as much data on tank combat at this level, and what he did have indicated a great deal more variability in loss rates. Examples of this can be found in the tables below.

These data points showed some consistency, with a mean of 6.96 and a standard deviation of 6.10, which is comparable to that for division/corps loss rates. Personnel casualty rates are higher and much more variable than those at the division level, however. Dupuy stated that more research was necessary to establish a higher degree of confidence and relevance of the apparent battalion tank loss ratio. So one potentially fruitful area of research with regard to near future combat could very well be a renewed focus on historical experience.

NOTES

Trevor N. Dupuy, Attrition: Forecasting Battle Casualties and Equipment Losses in Modern War (Falls Church, VA: NOVA Publications, 1995), pp. 41-43; 81-90; 102-103

As the U.S. Army and the national security community seek a sense of

As the U.S. Army and the national security community seek a sense of