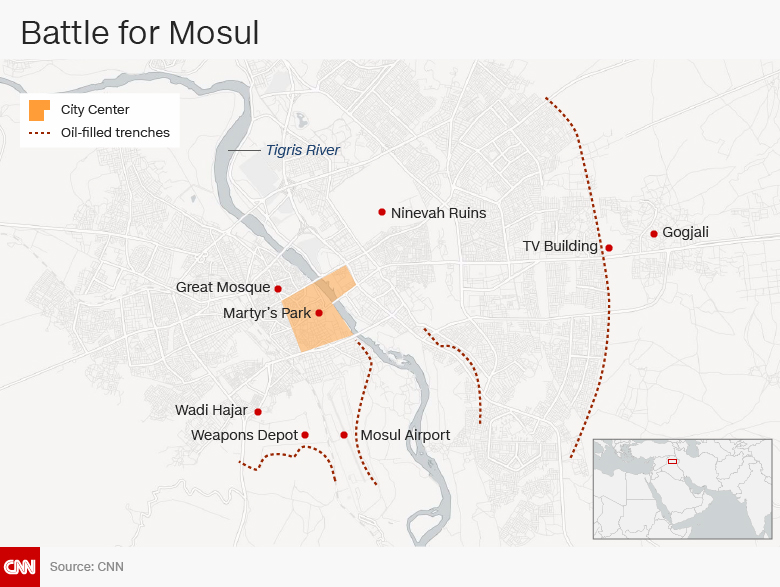

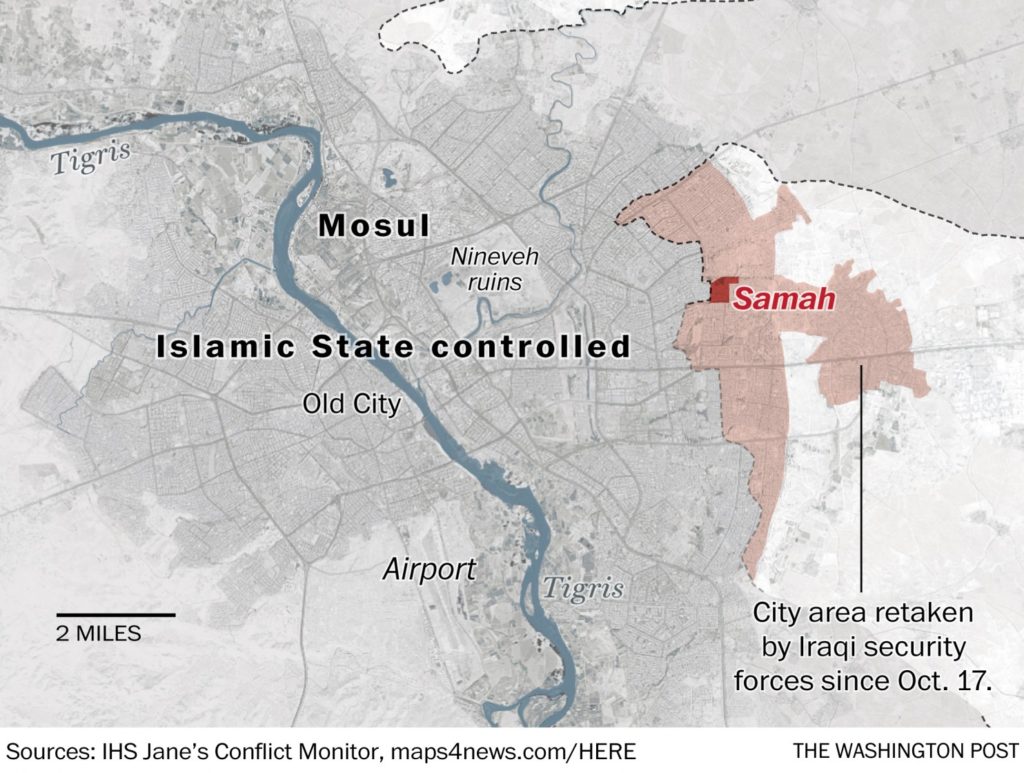

The Iraqi Interior Ministry announced on Tuesday that Daesh fighters have been cleared from a third of the city of Mosul east of the Tigris River. Pre-battle estimates by the Iraqis credited Daesh with 5,000-6,000 fighters in the city. The Iraqi government has deployed a polyglot force of 100,000 Defense and Interior Ministry troops, Kurdish peshmerga militia, and Shi’ite paramilitary fighters, supported by Western ground and air support, which have mostly surrounded the city. While official casualty estimates have not been announced, the Iraqis claimed to have killed 955 Daesh fighters and captured 108 on the southern front alone.

The Iraqi Interior Ministry announced on Tuesday that Daesh fighters have been cleared from a third of the city of Mosul east of the Tigris River. Pre-battle estimates by the Iraqis credited Daesh with 5,000-6,000 fighters in the city. The Iraqi government has deployed a polyglot force of 100,000 Defense and Interior Ministry troops, Kurdish peshmerga militia, and Shi’ite paramilitary fighters, supported by Western ground and air support, which have mostly surrounded the city. While official casualty estimates have not been announced, the Iraqis claimed to have killed 955 Daesh fighters and captured 108 on the southern front alone.

Despite the months of preparation and a clear objective, The Washington Post‘s Loveday Morris recently reported that Iraqi Army commanders were still “shaken” by the character of the fighting in Mosul’s urban environs. Although confident they will ultimately prevail, they doubt they will meet the objective set by Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi to bring the city under control by the end of the year.

Although the Iraqi military leaders profess surprise at the complexity of urban combat, their descriptions of do not reveal anything unprecedented in historical experience. Many comments reflect recurring problems the Iraqi Army has faced in its recent operations to clear Daesh from central and western Iraq.

- It is a bitter fight: street to street, house to house, with the presence of civilians slowing the advancing forces. Car bombs — the militants’ main weapon — speed out of garages and straight into advancing military convoys.

- “If there were no civilians, we’d just burn it all,” said Maj. Gen. Sami al-Aridhi, a counterterrorism commander. He was forced to temporarily pause operations in his sector Monday because too many families were clogging the street. “I couldn’t bomb with artillery or tanks, or heavy weapons. I said, ‘We can’t do anything.’ ”

- Militants wait to move between fighting positions until people fill the streets, using their presence as protection from airstrikes.

- Col. Arkan Fadhil calls in airstrikes from the U.S.-led coalition, but they are less forthcoming than in previous battles because of the presence of families, and are used only to defend Iraqi forces rather than backing them when they attack.

- Just a few Islamic State militants hidden in populated areas can cause tremendous chaos. [E]lite units stormed [six neighborhoods on] Nov. 4, on a day that was initially trumpeted as a success before it became clear that their early gains were not sustainable. After pushing forward with relatively little resistance, the forces were ambushed and cut off.

- Low-ranking officers in the field made some mistakes…such as pushing forward without waiting for other units or without properly clearing and securing areas, later getting ambushed and becoming surrounded and trapped. Since the pitched battles of Nov. 4, the [Iraqi] counterterrorism troops have adjusted their pace.

- [Iraqi counterterrorism forces] said they have had to slow down as they wait for other fronts to advance on the city. Whether they can fight inside when they reach it also remains to be seen. In the battle for the city of Ramadi, the elite counterterrorism troops ended up leading the entire fight after police and army forces struggled to move forward in their sectors.

- Restrictions in the use of airstrikes also slow their advance. But on Tuesday morning, more than half a dozen rockets roared overhead into the Mosul neighborhood of Tahrir. Officers identified them as TOS-1 short-range missiles, which unleash a blast of pressure over an area of several hundred square meters, devastating anything in their wake. The officers said they had been informed that there were no civilians in the target area. “We only use these missiles in empty areas,” Aridhi said. “We don’t use them in places with families in it.” They sometimes are used when Iraqi forces are under heavy direct fire, he said, because it is faster than sending coordinates to the coalition.

The Iraqi government has not yet released casualty figures for the fighting, but losses are perceived to be heavy by the combatants themselves.

Given the extreme ratio of forces involved, it would seem that Iraqi military leaders are on firm ground in their confidence of ultimate success. It also seems likely they are correct about the amount of time that will be needed to secure Mosul. The defending Daesh fighters are unlikely to be reinforced and cannot replace their combat losses. Simple arithmetic will do them in sooner or later. It also appears clear that the Iraqis are holding open an avenue of retreat to the west, in the hopes that surviving Daesh forces will simply withdraw rather than fight to the last.

It is somewhat unexpected that the Iraqi Army would be surprised by the character of urban fighting in Mosul, given that they have a good deal of recent experience with it. Although they did not lead the fights, Iraqi Army elements participated in the battles for Fallujah in 2004 and Sadr City in 2008. Iraqi government forces cleared Basra with Coalition assistance in 2008, and recaptured Tikrit, Ramadi, and Fallujah (again) over the last year.

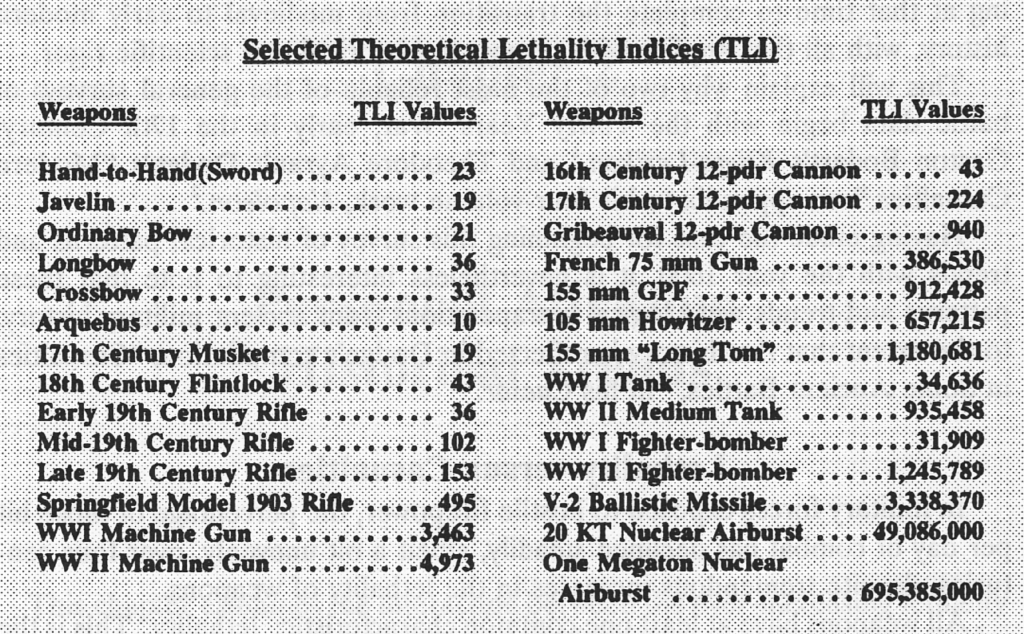

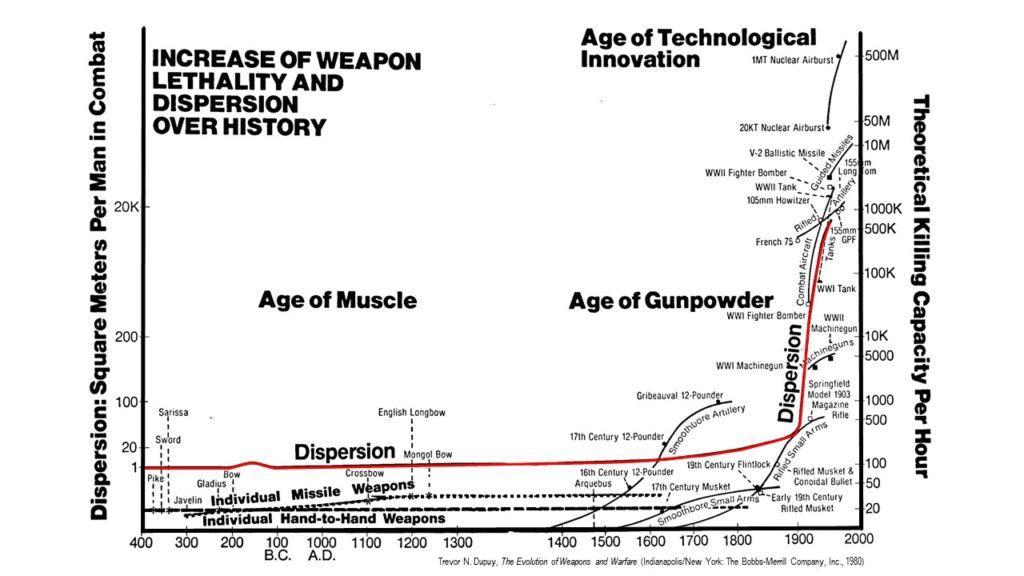

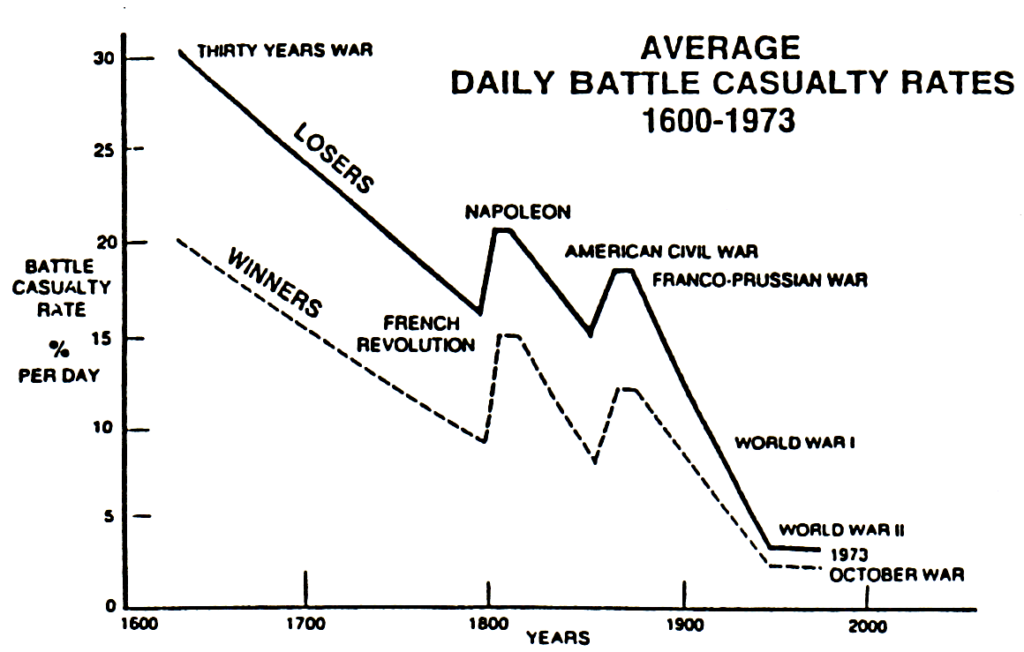

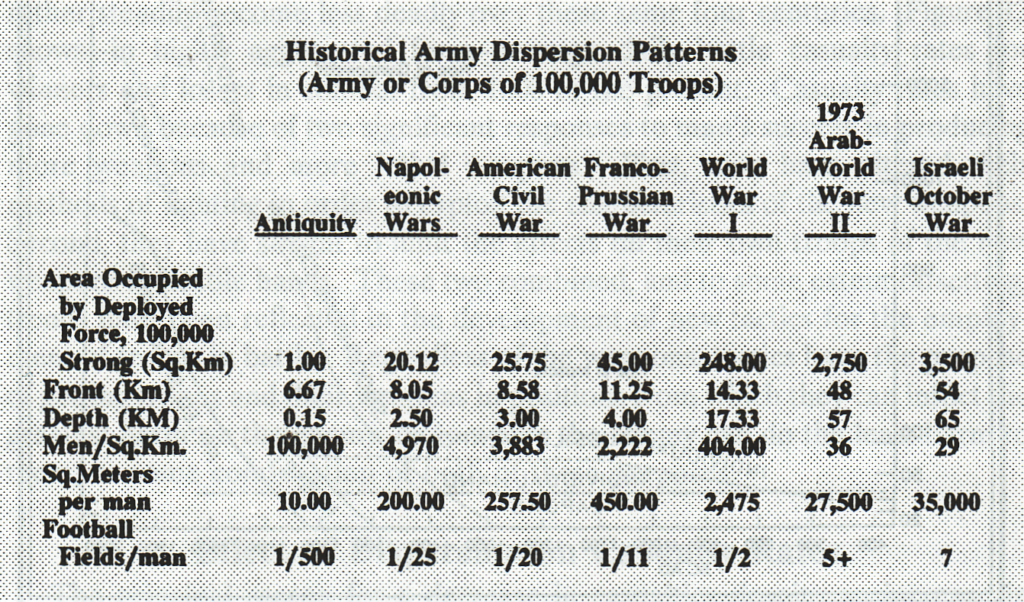

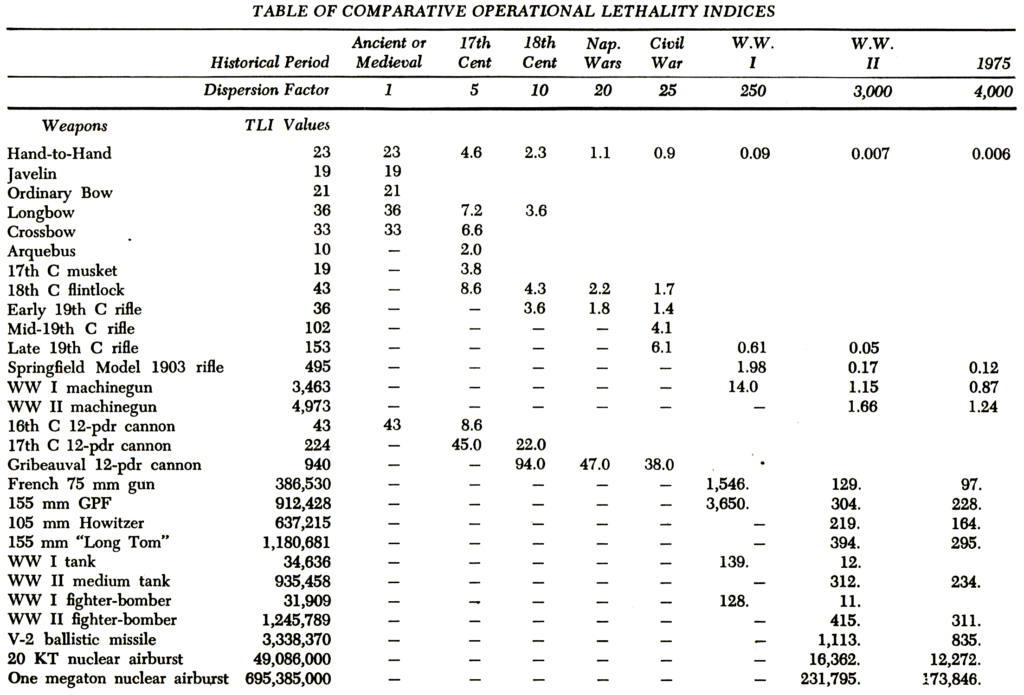

There exists a significant body of conventional wisdom that holds that urban combat is bloodier than non-urban combat, requires a higher ratio of attackers to defenders to be successful, and will be prevalent in the future. None of these conclusions is borne out by historical evidence. TDI has done a significant amount of analysis challenging the basis and conclusions of this conventional wisdom. War by Numbers, the forthcoming book by TDI President Chris Lawrence, goes into this research in great detail.

Over at his

Over at his