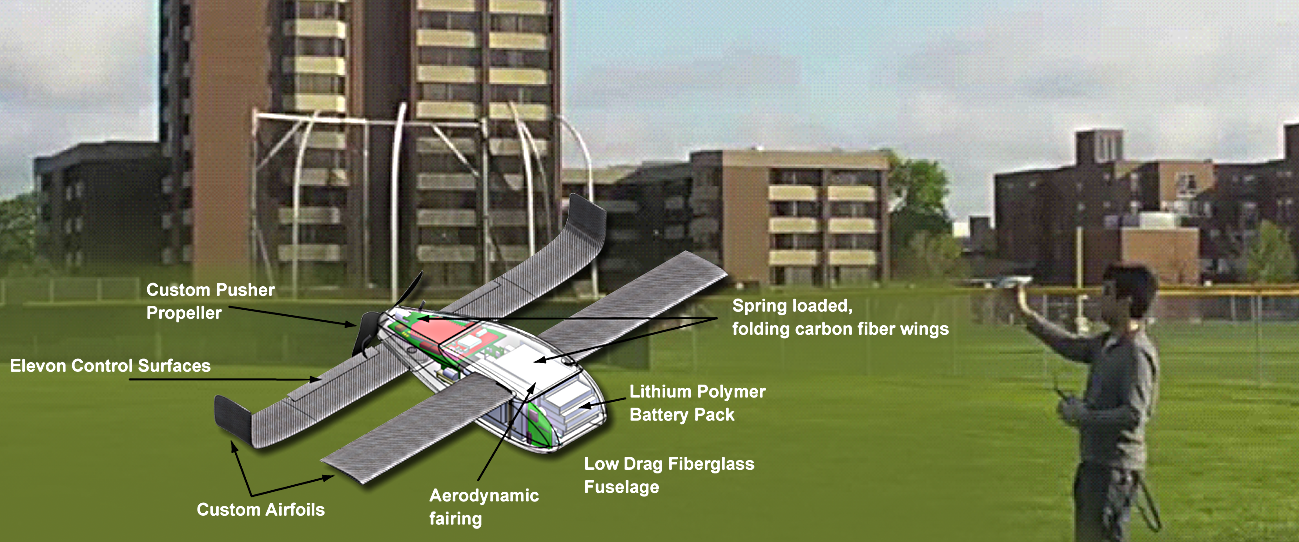

A conclusion that Fox alluded to in his article, but did not state explicitly, is that in a sense, the Russians “held back” in the design of their operations against the Ukrainians. It appears quite clear that the force multipliers derived from the battalion tactical groups, drone-enabled recon-strike model, and cyber and information operations capabilities generated more than enough combat power for the Russians to decisively defeat the Ukrainian Army in a larger “blitzkrieg”-style invasion and occupy most, if not all, of the country, if they had chosen to do so.

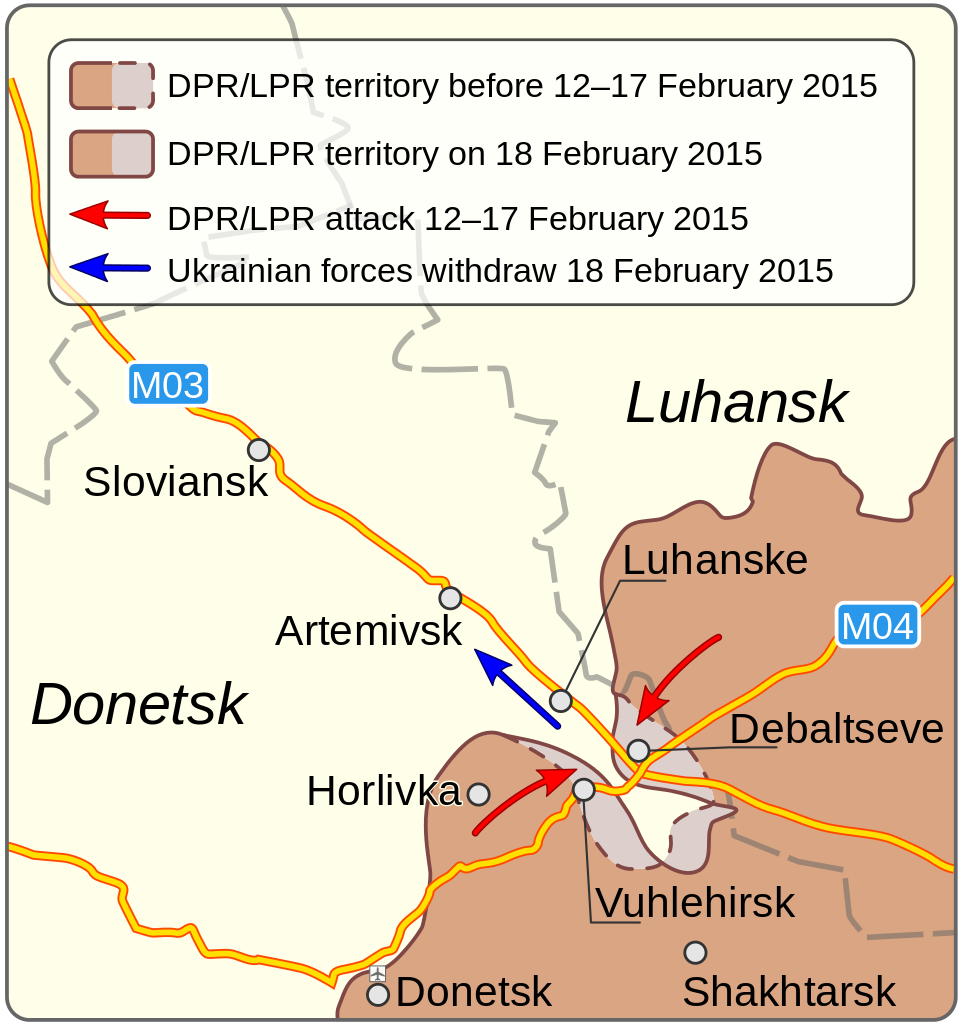

This clearly is not the desired political goal of the Russian government, however. Instead, the Russian General Staff carefully crafted a military strategy to fulfill more limited political goals, and creatively designed their operations to make full use of their tactical capabilities in support of that strategy.

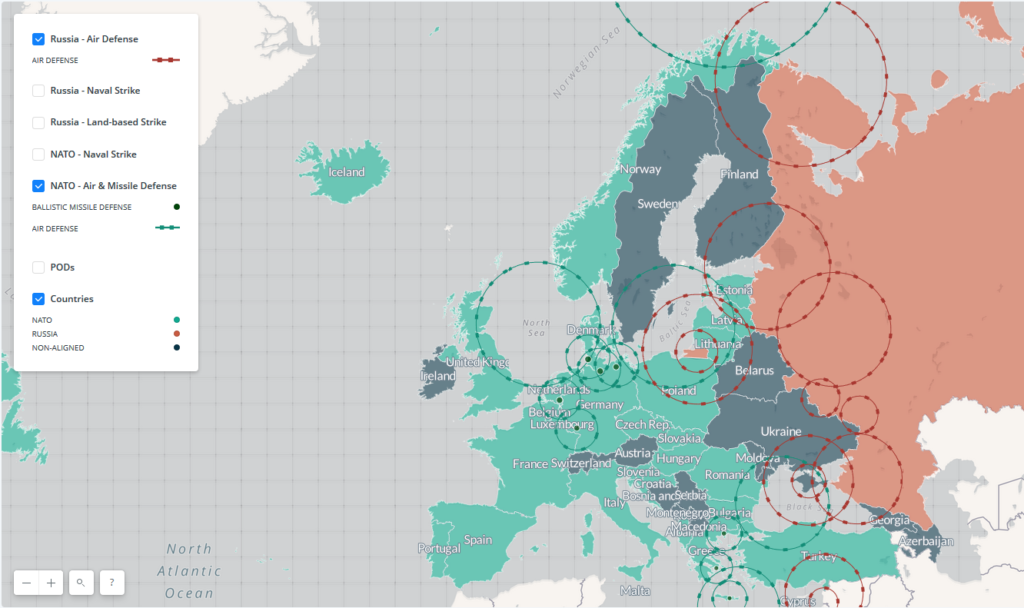

This successful Clausewitizan calibration of policy, strategy, operations, and tactics by the Russians in Ukraine and Syria should give the U.S. real concern, since itself does not currently seem capable of a similar level of coordination or finesse. Now, the Russian achievements against the relatively hapless Ukrainians, or in Syria, where the ultimate outcome remains very much indeterminate, are no guarantee of future success against more capable and well-resourced opponents. However, it does demonstrate what can be achieved with a relatively weak strategic hand to play through a clear unity of political purpose and military means. This has not been the U.S.’s strong suit historically, and it is unclear at this juncture whether that will change under the incoming Trump administration.