I updated this post with tables! Click through to the original post and scroll to the bottom.

Excellence in Historical Research and Analysis

Excellence in Historical Research and Analysis

Mystics & Statistics

Defeating an Insurgency by Air II

One of my earliest blog posts, done in December 2015 was on “Defeating an Insurgency by Air.” It was in part inspired by the Republican debate at the time and people talking about “carpet bombing” ISIL.

The post is here: https://dupuyinstitute.dreamhosters.com/2015/12/29/defeating-an-insurgency-by-air/

The same article is was posted on the History News Network: http://historynewsnetwork.org/article/161601

An expanded article was posted on the Small War Journal: http://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/airpower-just-part-of-the-counterinsurgency-equation

I gather the part of the article that gives people heartburn is: “So, we are left to state that we cannot think of a single insurgency that was defeated by airpower, primarily defeated by airpower, or even seriously undermined by airpower. Perhaps there is a case we are missing. It is probably safe to say that if it has never successfully been done in over a hundred insurgencies over the last hundred years, then it is something not likely to occur now.”

Now, we do go on a hunt for other cases. This led to the follow-up blog posts:

This last post was actually not tagged as an “air power” subject, but I felt it was particularly relevant….and yes, we do have two blog posts with the same title. But this second one has this cool graph:

$5,000 Book

Just browsing Amazon.com and notice that one of the re-sellers has my Kursk book up for sale for $5,008.00: https://www.amazon.com/gp/offer-listing/0971385254/ref=dp_olp_all_mbc?ie=UTF8&condition=all

Really? Has he sold any at that price? I would be willing to part with a couple of my author’s copies at that price.

Anyhow, the book is still available from Aberdeen Books at a much more modest $195: http://www.aberdeenbookstore.com/

See A Russian Su-35 Defy The Laws Of Physics

If you want to watch a breath-taking aerial maneuver by a Russian Sukhoi Su-35 Flanker-E fighter at the 2017 International Aviation and Space Show outside Moscow, click on the link below.

Действуют ли законы физики на Су-35? #МАКС2017 pic.twitter.com/przaI59G2l

— Вежливые люди (@vezhlivo) July 20, 2017

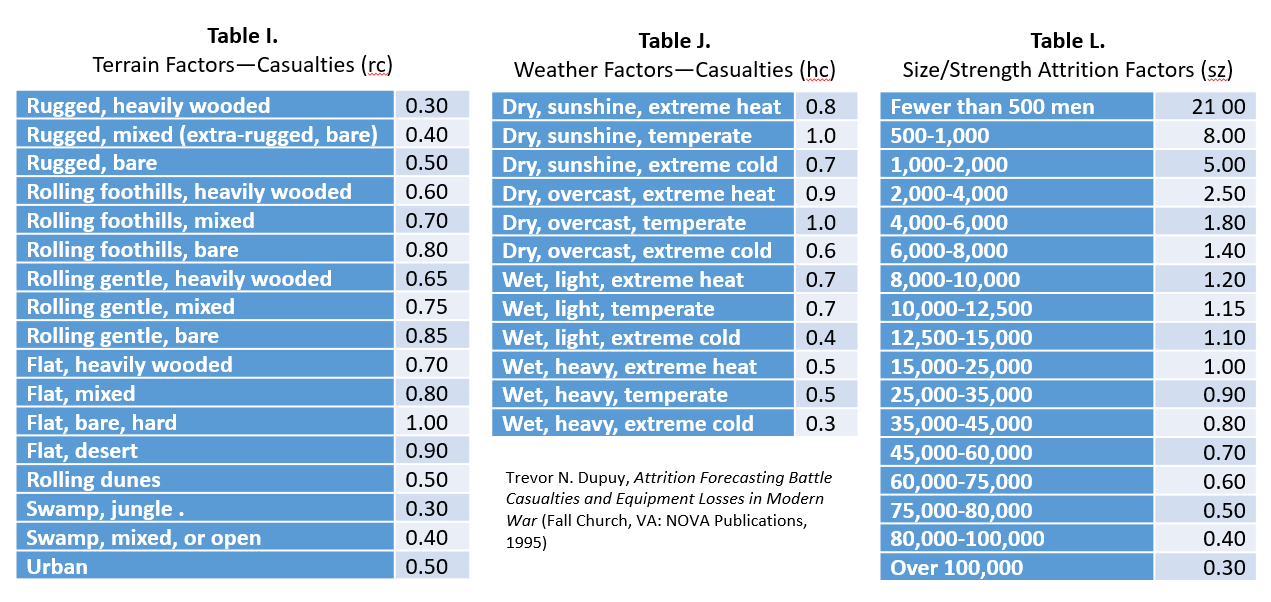

Human Factors In Warfare: Combat Intensity

Trevor Dupuy considered intensity to be another combat phenomena influenced by human factors. The variation in the intensity of combat is an aspect of battle that is widely acknowledged but little studied.

No one who has paid any attention at all to historical combat statistics can have failed to notice that some battles have been very bloody and hard-fought, while others—often under circumstances superficially similar—have reached a conclusion with relatively light casualties on one or both sides. I don’t believe that it is terribly important to find a quantitative reason for such differences, mainly because I don’t think there is any quantitative reason. The differences are usually due to such things as the general circumstances existing when the battles are fought, the personalities of the commanders, and the natures of the missions or objectives of one or both of the hostile forces, and the interactions of these personalities and missions.

From my standpoint the principal reason for trying to quantify the intensity of a battle is for purposes of comparative analysis. Just because casualties are relatively low on one or both sides does not necessarily mean that the battle was not intensive. And if the casualty rates are misinterpreted, then the analysis of the outcome can be distorted. For instance, a battle fought on a flat plain between two military forces will almost invariably have higher casualty rates for both sides than will a battle between those same two forces in mountainous terrain. A battle between those two forces in a heavy downpour, or in cold, wintry weather, will have lower casualties than when the forces are opposed to each other, under otherwise identical circumstances, in good weather. Casualty rates for small forces in a given set of circumstances are invariably higher than the rates for larger forces under otherwise identical circumstances.

If all of these things are taken into consideration, then it is possible to assess combat intensity fairly consistently. The formula I use is as follows:

CI = CR / (sz’ x rc x hc)

When: CI = Combat Intensity Measure

CR = Casualty rate in percent per day

sz’ = Square root of sz, a factor reflecting the effect of size upon casualty rates, derived from historical experience

rc = The effect of terrain on casualty rates, derived from historical experience

hc = The effect of weather on casualty rates, derived from historical experience

I then (somewhat arbitrarily) identify seven levels of intensity:

0.00 to 0.49 Very low intensity (1)

0.50 to 0.99 Low intensity (56)

1.00 to 1.99 Normal intensity (213)

2.00 to 2.99 High intensity (101)

3.00 to 3.99 Very high intensity (30)

4.00 to 5.00 Extremely high intensity (17)

Over 5.00 Catastrophic outcome (20)

The numbers in parentheses show the distribution of intensity on each side in 219 battles in DMSi’s QJM data base. The catastrophic battles include: the Russians in the Battles of Tannenberg and Gorlice Tarnow on the Eastern Front in World War I; the Russians on the first day of the Battle of Kursk in July 1943; a British defeat in Malaya in December, 1941; and 16 Japanese defeats on Okinawa. Each of these catastrophic instances, quantitatively identified, is consistent with a qualitative assessment of the outcome.

[UPDATE]

As Clinton Reilly pointed out in the comments, this works better when the equation variables are provided. These are from Trevor N. Dupuy, Attrition Forecasting Battle Casualties and Equipment Losses in Modern War (Fall Church, VA: NOVA Publications, 1995), pp. 146, 147, 149.

Economics of Warfare 19 – 1

Continuing with the nineteenth and second to last lecture from Professor Michael Spagat’s Economics of Warfare course that he gives at Royal Holloway University. It is posted on his blog Wars, Numbers and Human Losses at: https://mikespagat.wordpress.com/

This lecture continues the discussion of terrorism, a subject we often deliberately avoid. We actually don’t even have a category for terrorism on the blog, in part because I consider it a tool of an insurgency, not a separate form of warfare.

On the first slide is a paper on the determinants of media attention for terrorist attacks. This is a significant subject as terrorism does rely on media attention to make their points. If there was no coverage……then the terrorist act would be relatively ineffective. The purpose of terrorism is not to kill people, it is to attract attention. Modern international terrorism started with the Palestinian Black September attack on the Munich Olympics in 1972, which turned the Palestinian issue from a Middle East concern into an issue that now garnered world wide attention.

Anyhow, the lecture starts with a paper by Michael Jetter, which is linked to on page 1 (one of the very nice things about this lecture series is that all the various papers he discusses are linked in the lecture…providing a extensive collection of interesting and useful papers to read). The question is “…why do some attacks generate more coverage than others do?” The answer is on slides 10 and 12, but the short answer is: attacks in wealthier countries, countries that trade with the U.S., that are closer to the U.S. get more coverage (in the New York Times).

Not sure how really meaningful this is except to note that obviously, terrorist attacks in Canada are going to get a lot more attention in the U.S. newspapers than terrorist attacks in Sri Lanka.

Anyhow, this is going to turn into a two-part posting, so will do the rest later this week. The link to his lecture is here: http://personal.rhul.ac.uk/uhte/014/Economics%20of%20Warfare/Lecture%2019.pdf

Russian Protestors

It probably does not come as a surprise to most who read this blog that I am not favorably disposed to the presidency of Vladimir Putin. I found the following article in the Christian Science Monitor to be interesting: What is Stirring Russia’s Youth to Rally Around Alexei Navalny

Just a couple of quotes from the article that caught my eye:

Mikhail Aralov: “In our country the population is called ‘the people.’ when in fact we are citizens. ‘The people’ need bread and circuses, but citizens need civil institutions.”

Dmitry Zabelin: “I am tired of corruption, the state of human rights, and all the hypocrisy that you see every day. I’m very worried about how Putin is trying to restore the Soviet Union; Russia should be trying to become a Western country and part of the world.”

Anyhow, I wish them the best.

Russian Arms Sales

Little article on Russian arms sale, not a subject we track: http://www.businessinsider.com/this-how-many-countries-buy-weapons-from-russia-2017-7

The article is based upon the first DIA report on the Russia/Soviet military that they have published since 1991. I have not read the report but note that the article states: “The DIA report, however, has been criticized by some for being too hawkish, just like previous DIA reports on the Soviet Union.” I have not reviewed the DIA report and don’t have the ability to really do so properly, but I do remember well their old reports in the 1980s, and they were certainly “too hawkish.” They clearly overemphasized Soviet strengths and ignored many of their weaknesses. The Soviet Union collapsed in 1991.

More to the point, we engaged one of the Soviet armed countries, Iraq, in the Gulf War in 1991; and we had a chance to review their military in the 1990s (something which I have some knowledge of). I have never seen a systematic analysis of what the defense and intelligence analysts were saying in the 1980s compared to what they were able to see in the 1990s, but there is an interesting story there about our misperceptions and failures to understand the Soviet military.

Human Factors In Warfare: Surprise

Trevor Dupuy considered surprise to be one of the most important human factors on the battlefield.

A military force that is surprised is severely disrupted, and its fighting capability is severely degraded. Surprise is usually achieved by the side that has the initiative, and that is attacking. However, it can be achieved by a defending force. The most common example of defensive surprise is the ambush.

Perhaps the best example of surprise achieved by a defender was that which Hannibal gained over the Romans at the Battle of Cannae, 216 BC, in which the Romans were surprised by the unexpected defensive maneuver of the Carthaginians. This permitted the outnumbered force, aided by the multiplying effect of surprise, to achieve a double envelopment of their numerically stronger force.

It has been hypothesized, and the hypothesis rather conclusively substantiated, that surprise can be quantified in terms of the enhanced mobility (quantifiable) which surprise provides to the surprising force, by the reduced vulnerability (quantifiable) of the surpriser, and the increased vulnerability (quantifiable) of the side that is surprised.

I have written in detail previously about Dupuy’s treatment of surprise. He cited it as one of his timeless verities of combat. As one of the most powerful force multipliers available in battle, he calculated that achieving complete surprise could more than double the combat power of a force.

Mosul Mop-Up

By the way, there is still some fighting going on in Mosul (no link).