In an article published by the Association of the U.S. Army last November that I missed on the first go around, U.S. Army Colonel Eric E. Aslakson and Lieutenant Colonel Richard T. Brown, (ret.) make the argument that “Staff colonels are the Army’s innovation center of gravity.”

In an article published by the Association of the U.S. Army last November that I missed on the first go around, U.S. Army Colonel Eric E. Aslakson and Lieutenant Colonel Richard T. Brown, (ret.) make the argument that “Staff colonels are the Army’s innovation center of gravity.”

The U.S. defense community has settled upon innovation as one of the key methods for overcoming the challenges posed by new technologies and strategies adapted by potential adversaries, as articulated in the Third Offset Strategy developed by the late Obama administration. It is becoming clear however, that a desire to innovate is not the same as actual innovation. Aslakson and Brown make the point that innovation is not simply technological development and identify what they believe is a crucial institutional component of military innovation in the U.S. Army.

Innovation is differentiated from other forms of change such as improvisation and adaptation by the scale, scope and impact of that value creation. Innovation is not about a new widget or process, but the decisive value created and the competitive advantage gained when that new widget or process is applied throughout the Army or joint force…

However, none of these inventions or activities can rise to the level of innovation unless there are skilled professionals within the Army who can convert these ideas into competitive advantage across the enterprise. That is the role of a colonel serving in a major command staff leadership assignment…

These leaders do not typically create the change. But they have the necessary institutional and operational expertise and experience, contacts, resources and risk tolerance to manage processes across the entire framework of doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership and education, personnel and facilities, converting invention into competitive advantage.

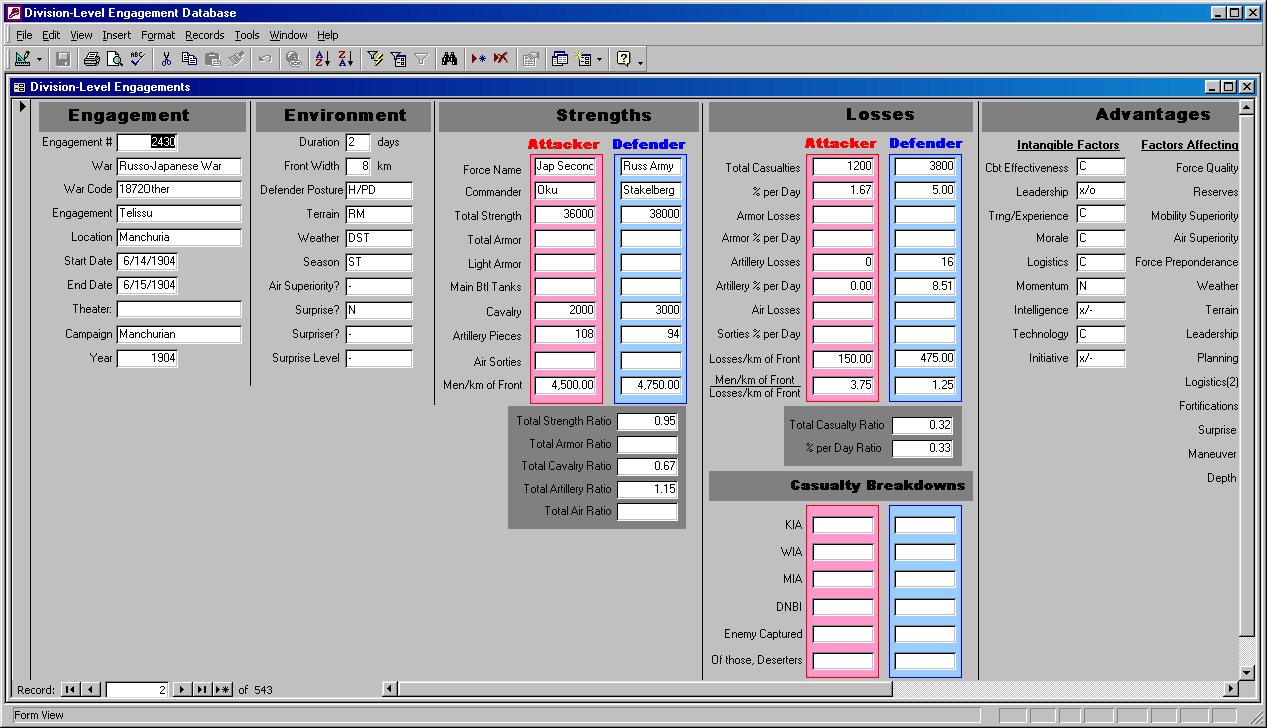

In his seminal book, The Evolution of Weapons and Warfare (Indianapolis, IN: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., 1980), Trevor Dupuy noted a pattern in the historical relationship between development of weapons of increasing lethality and their incorporation in warfare. He too noted that the crucial factor was not the technology itself, but the organizational approach to using it.

When a radically new weapon appears and is first adopted, it is inherently incongruous with existing weapons and doctrine. This is reflected in a number of ways; uncertainty and hesitation in coordination of the new weapon with earlier ones; inability to use it consistently, effectively, and flexibly in offensive action, which often leads to tactical stalemate; vulnerability of the weapon and of its users to hostile countermeasures; heavy losses incident to the employment of the new weapon, or in attempting to oppose it in combat. From this it is possible to establish the following criteria of assimilation:

- Confident employment of the weapon in accordance with a doctrine that assures its coordination with other weapons in a manner compatible with the characteristics of each.

- Consistently effective, flexible use of the weapon in offensive warfare, permitting full employment of the advantages of superior leadership and/or superior resources.

- Capability of dealing effectively with anticipated and unanticipated countermeasures.

- Sharp decline in casualties for those employing the weapon, often combined with a capability for inflicting disproportionately heavy losses on the enemy.

Based on his assessment of this historical pattern, Dupuy derived a set of preconditions necessary for a successful assimilation of new technology into warfare.

- An imaginative, knowledgeable leadership focused on military affairs, supported by extensive knowledge of, and competence in, the nature and background of the existing military system.

- Effective coordination of the nation’s economic, technological-scientific, and military resources.

- There must exist industrial or developmental research institutions, basic research institutions, military staffs and their supporting institutions, together with administrative arrangements for linking these with one another and with top decision-making echelons of government.

- These bodies must conduct their research, developmental, and testing activities according to mutually familiar methods so that their personnel can communicate, can be mutually supporting, and can evaluate each other’s results.

- The efforts of these institutions—in related matters—must be directed toward a common goal.

- Opportunity for battlefield experimentation as a basis for evaluation and analysis.

Does the U.S. defense establishment’s organizational and institutional approach to innovation meet these preconditions? Good question.