When doing historical research questions often tend to lead to more questions which lead to more questions. You never seem to get to a final answer, you just move the questions further along. In my attempt to sort out the Staudegger fight of 8 July 1943, I ended up trying to figure out where the Das Reich SS Division’s Tiger tanks were (as one or two may have been involved in the fight against the II Tank Corps). That question led me to look back at the Tiger tank strengths of the Das Reich on the 8th, which led me to review the whole period from 6 to 9 July 1943. There is a hole there in the Das Reich records. This happens a lot (especially with the SS, who were not the best record keepers).

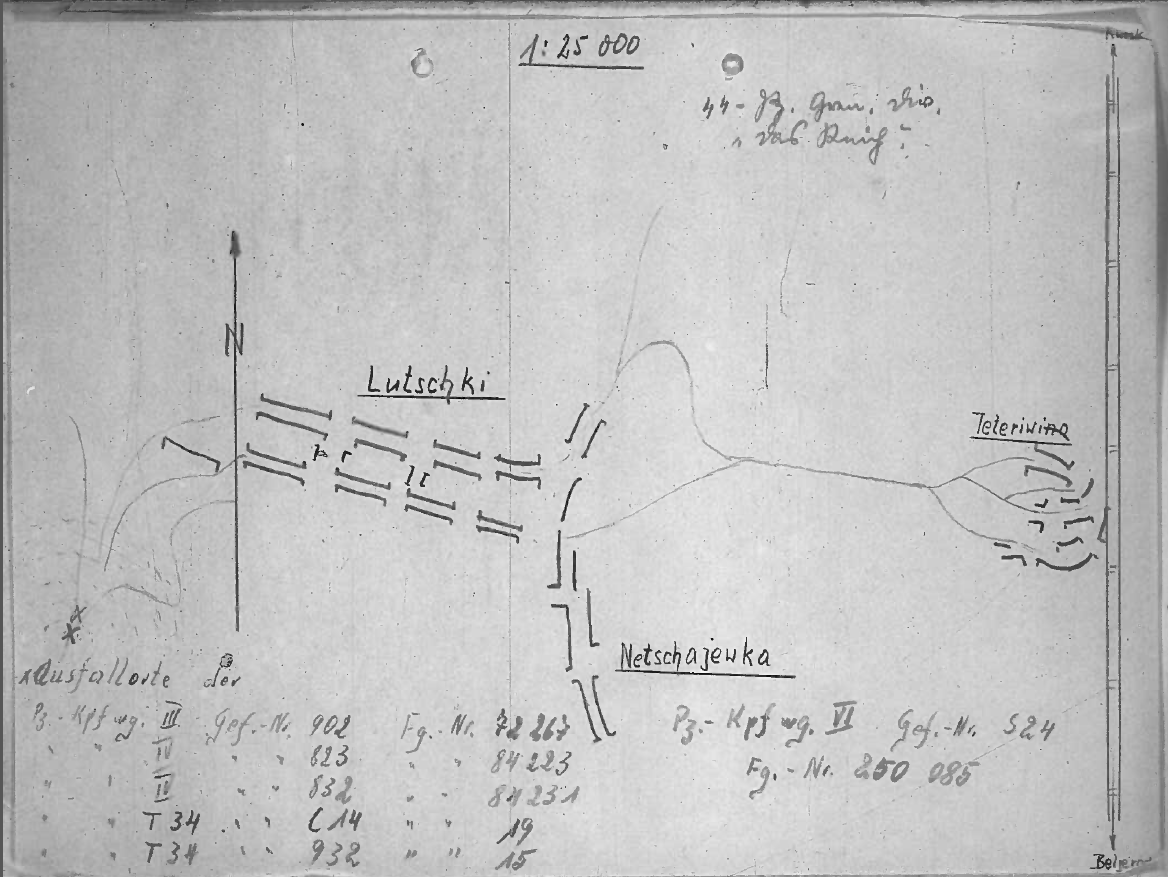

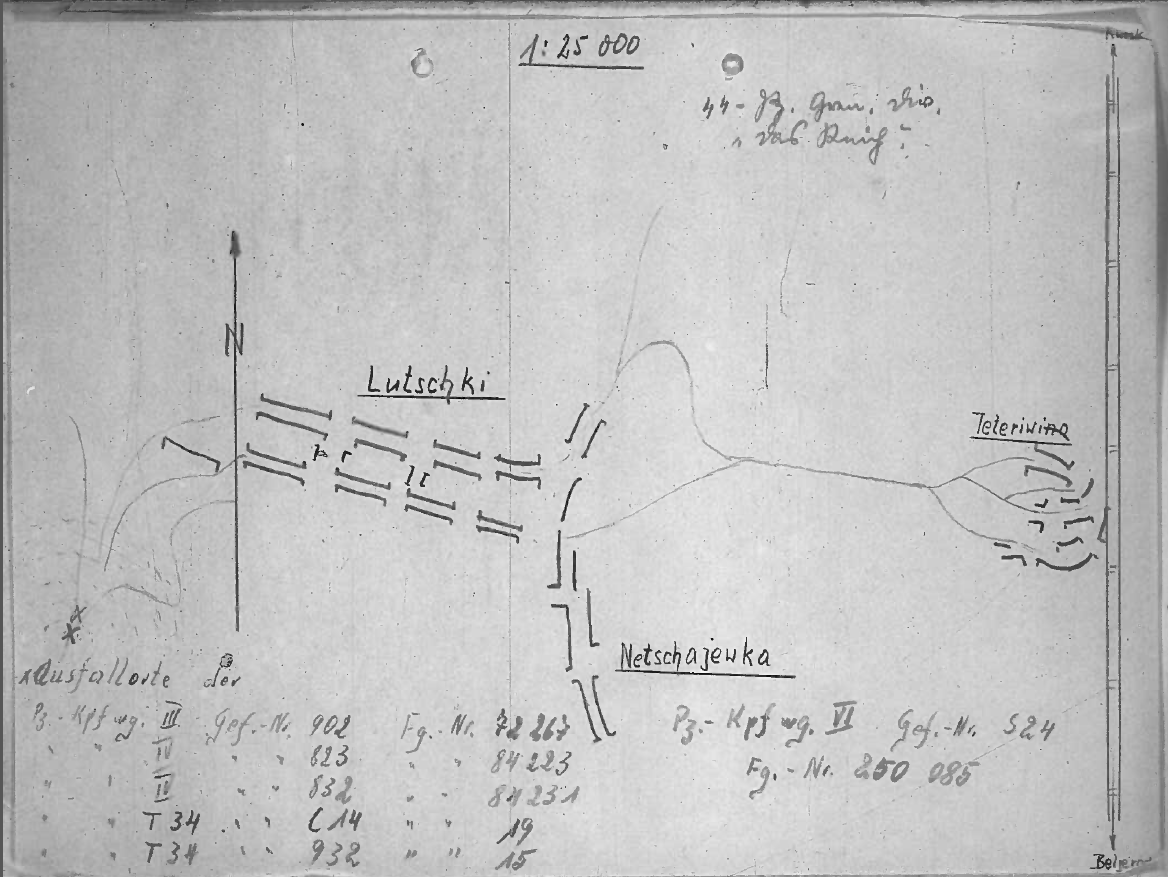

This then led me back to a diagram showing 6 tanks destroyed in a gully about one kilometer SSW of Luchki (south), roughly at grid 246404. They were one Panzer III, two Panzer IVs, 2 German T-34s and one Panzer VI (serial number 250085). See T313, R390, page 839.

If six tanks were destroyed there, then how many were damaged (could be 30+)? This would be a significant fight. Das Reich took Luchki on 6 July. There is no detailed records of any significant armor action there that I have found. Did six tanks just happen to get destroyed there because of a series of accidents and odd shots, or is this the ditch where they just happened to storing all their seriously damaged tanks, or as the map only has two “X’s” marked on it are the other four loss locations not marked, or is this an indication of a much larger undocumented fight that occurred on 6 July (or perhaps it was later). Right now, my Kursk book has several statements about the fighting at Luchki that does not indicate much armor action. They include:

It brought Luchki under attack at 1030 [6 July] but by 1045, the division was complaining that its attacks on height 243.2 was not making progress. Das Reich put its Der Fuehrer SS Regiment foremost and after overcoming stiff resistance, in particular from antitank guns and artillery, concentrated the fire of all heavy weapons onto hill 246.3, which the regiment then seized at 1130 [this height is located a little over 2 kilometers south of the tank “graveyard” in question]. On the other hand, the Adolf Hitler SS Division claims it seized hill 246.3 at 1115. (page 468-469)

But in the Corps log book (T313, R368) there is further detail for 6 July.

1115: message to commanding general: Das Reich attacking with panzers against Hill 246.3. Enemy strength unclear. Intention: Advance, go around Luchki on both sides.

1125: From Das Reich: Position west of Hill 246.3 in our hands, very fluid battle moving eastward.

1130: Message to commanding general: Hill 246.3 in our hands.

1340: Message to commanding general: 2nd Pz Regt [Das Reich] at Hill 232.0; Regiment Der Fuehrer apparently in Luchki. Ordering a change of position for the command post.

1405: From Das Reich: Regiment Der Fuehrer in combat in Luchki. Panzers moving against Hill 232.0.

1515: Orders to Das Reich: Continue attacking, objective Prokhorovka.

Back to my book:

By 1340, the panzer regiment had taken [probably should say were at] height 232.0 and Der Fuehrer SS Regiment had taken Luchki (1320 Berlin time). Nechayevka also fell to the Germans.

This is from page 469, I cannot locate height 232.0, but do not think it is near Luchki. It is stated for 6 July that end of the day the division succeeded in capturing Luchki (grid 2840), Sobachevskii (295440) and Kalinin (305460, as well as hill 232.0 (????), Oserovskii (2946) and the wooded section just NW of there. As this locations tend to be listed from left to right, this would indicate that height 232.0 is around 5 kilometers north of Luchki.

Our battalion had fought its way through the enemy entrenchments by the early hours of the afternoon and we occupied a place called Luckhi [the one on the Lipovyii Donets]. We reached the perimeter of this village that laid toward the enemy together with the first Grenadiers, but were completely out of ammunition. There was nothing left to do except wait for ammunition resupply under cover of this village.

While we waited for supply vehicles, cleaned out guns and prepared everything for loading ammunition, we were unexpectedly attacked by our own planes. A squadron of Hs-123s [German ground attack planes] dropped their bombs in a diving attack on Luchki. The bombs kept impacting closer until were hurriedly laid flat on the ground next to the vehicle tracks. Lots of bad language greeted the departing planes’ farewell. After this incident we removed the flag stretches across the hood for identification by air and instead the aerial observer on duty had to wave it forcefully whenever friendly planes were approaching. This apparently did the trick, as friendly planes no longer bothered us.

…In a great rush we filled up the magazines, transferred an extra few cases of ammunition over to our vehicle, refueled and quenched our thirst with the water from the containers brought along. We then closed up to the Grenadiers on the southern perimeter of Luchki at high speed. Another gun from our platoon was already engaged in an exchange of fire there. It took several more hours until the village had been taken.

There was an elevation behind Luchki that the enemy had to traverse in his retreat. We caught the enemy infantry columns with our 20mm guns on the bare include that provided almost no cover and caused great losses among them. The immediate follow up of our battalion was prevent by this bare terrain, through, mainly because of heavy fire from the flank to which we were exposed without protection. There was no way to move forward from there. Sharpshooters fired from extremely well camouflaged positions on every man who made a move and forced us to exercise greatest care. We repeatedly attempted to force enemy sharpshooters from their assumed positions by firing single, targeted shots. But the drama only ceased at nightfall. We remained ready for action throughout the night in position. There was no way to catch sleep as the exchange of fire never ceased completely at night.

The last four paragraphs are from page 470, from the interview with Private Kurt A. Kaufmann, loader with 14th company of the antiaircraft battery, Der Fuehrer SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment.

During the fighting near Luchki, the Tiger company claimed 12 T-34s. Also they report that a Russian armored train entered battle, causing some losses and was then set ablaze by the Tigers! (page 470, passage taken from Wolfgang Schneider, Tigers in Combat, Volume II, page 143)

The railroad track is four kilometers were of Luchki.

By the end of the day, the Das Reich SS Division was able to capture Luchki, Sobachevskii, Kalinin, heght 232.0, Ozerovskii, and the wooded section northwest of Ozerovskii. It lost 30 tanks and assault guns this day. (page 472)

This does not really indicate why there were 6 destroyed tanks to the SSW of Luchki (south). The town is hardly mentioned elsewhere in my book and does not appear to have been further fought over, although Luchki (north) was.

P.S. The Henschel 123 painting is from: http://keefsblog.blogspot.com/2012/05/henschel-hs-123.html

This series of posts was based on the article “Iranian Casualties in the Iran-Iraq War: A Reappraisal,” by H. W. Beuttel, originally published in the

This series of posts was based on the article “Iranian Casualties in the Iran-Iraq War: A Reappraisal,” by H. W. Beuttel, originally published in the