There is a post-war account (published in 1990) by the LSSAH Division chief of staff Major Rudolf Lehmann where he states that the II Panzer Battalion had 33 panzers. That is sometimes interpreted as meaning that the afternoon or evening of 11 July 1943 there remained near height 252.2 around 33 panzers. This would be II Panzer Battalion, the Battalion HQ and possibly the Panzer Regiment HQ. He specifically states: “Sturmbannfuehrer Gross [commander of II Panzer Battalion] managed to bring this battle to a successful conclusion despite the crushing numerical superiority of the enemy; he had at this point only thirty-three Panzers.” (page 236). I doubt this is a number he remembered of the top of his head 47 years after the fact, so I assume he got it from a diary or notes or a document from the time. I have not seen this figure documented anywhere else.

Now, this could mean that they had 33 tanks on the evening of the 11th or before the fighting on the 12th or after the fighting on the morning of the 12th. If they had 33 tanks after the fighting on the morning of the 12th, then this may imply that they started the battle with 37 tanks. Now, this quote is placed in the narrative for 12 July right after discussing the 6th panzer company having seven tanks and having lost 4 in their retreat. Regardless it appears the II Panzer Battalion had either 33 or 37 tanks. The problem is that the Panzer Regiment is reported to have 69 tanks on the evening of 11 July.

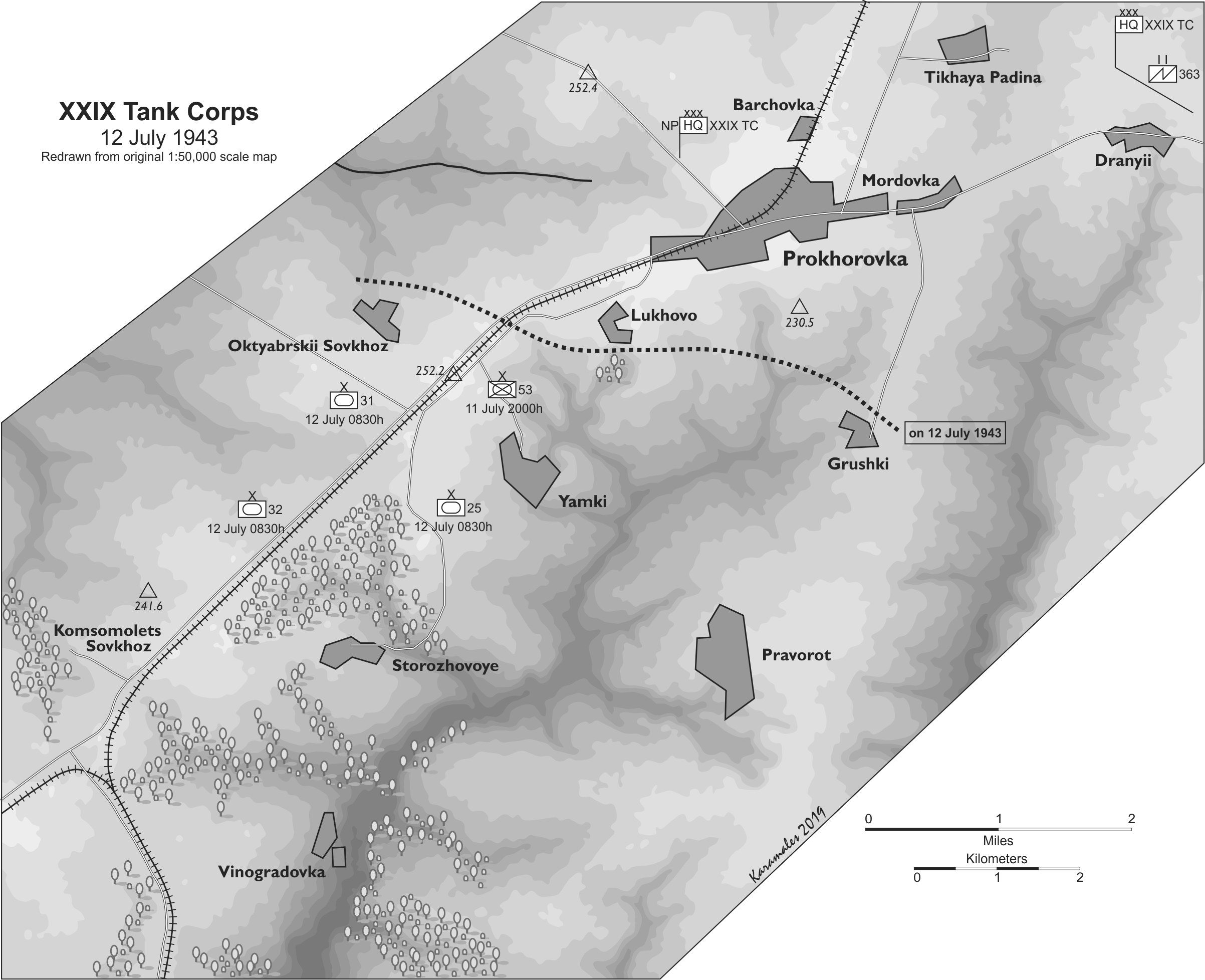

Height 252.2 is just to the southwest of Prokhorovka. The panzer were then pulled back to behind the tank ditch except for Captain Rudolf von Ribbentrop’s 6th Panzer Company. Captain Ribbentrop was the son of the Nazi foreign minister. So the 6th Panzer Company remained near 252.2 while the 5th and 7th Panzer Companies moved further back to the rear. According to Lehmann, these two panzer companies were located around 800 meters to the rear.

According to Ribbentrop, the 6th panzer company had 7 tanks on the morning of 12 July. Lehmann also states that. One could infer from this that the 5th and 7th panzer companies each had around 12 to 16 tanks, less 2 or 3 tanks for the battalion command (7 + 12 + 12 + 2 = 33 or 7 – 4 + 15 + 16 + 3 = 37)

Now, according to the Kursk Data Base, as of the evening of 11 July the LSSAH Division had 2 Panzer Is, 4 Panzer IIs, 1 Panzer III short, 4 Panzer III longs, 7 Panzer III Command tanks, 47 Panzer IV longs, and 4 Panzer VIs for a total of 69 tanks in the panzer regiment (see footnote 34, page 165, of The Battle of Prokhorovka).

So, 69 tanks in the panzer regiment and the II Panzer Battalion appears to have had 33 or 37 tanks. There are 4 Tigers for 13th Panzer Company, which was not with them. That would leave 28 to 32 or so tanks for an ersatz I Panzer Battalion and the panzer regiment headquarters (2 or 3 command tanks and probably the 2 Panzer Is and 4 Panzer IIs). This leaves two Panzer III Command, four Panzer III longs and 13 to 18 Panzer IVs for an ersatz I Panzer Battalion.

Now, I have been arguing for a while that the LSSAH may well have had two operational panzer battalions at Kursk. This debate first started as a series of emails between Niklas Zetterling and I, and continued as a series of posts and debated between Dr. Wheatley and I. If Lehmann’s account is correct, and if Ribbentrop’s account on 12 July is correct, then this would strongly argue that there was indeed an ersatz I Panzer Battalion at Prokhorovka.

My previous post on the subject is:

Did the LSSAH have 3 panzer panzer companies, 4 panzer companies or two panzer battalions in July 1943? | Mystics & Statistics (dupuyinstitute.org)

P.S. Lehmann’s book is references in July an 8th Panzer Company. It is identified on page 450 as under command of “Ost. Amberger” with the note “The 8. Kompanie did not take part on Operation Zitadelle because of an insufficient number of panzers.” With the LSSAH Division starting the battle with 90 Panzer IIIs and IVs, this statement does not make sense unless there was an ersatz first panzer battalion.