The biggest problem with the kill claims related to the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler (LSSAH) Division’s Tiger company on 5 July 1943 is that they claim dozens of T-34s killed on the 5th of July, when there were few in the area.

These specific claims are discussed here:

Panzer Aces Wittmann and Staudegger at Kursk – part 1

There were no units armed with T-34s that were attached to the Sixth Guards Army, and the armored units in the area with T-34s were not in action for most of the 5th (this would include the III Mechanized Corps and the II Guards Tank Corps). So either the LSSAH Tigers shot up a lot of M-3 Lees and Stuarts and they have become T-34s in the retelling, or the claims are just grossly inflated or flat out wrong.

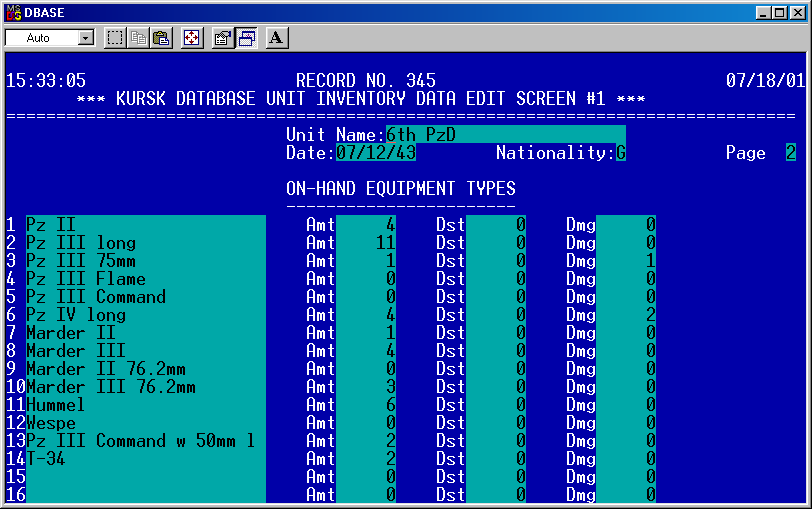

But….there may have been a few T-34s in the area. According to the March-April 1944 Soviet General Staff Study done on Kursk, 10 or 15 tanks were deployed in the fortified areas as part of the defense. See page 284 of my Kursk book. But, in the unit records we had, we never had a report on them (including in the Sixth Guards Army records). We have not seen any record of them other than the single report in the General Staff Study.

So there were 10 or 15 tanks deployed in the fortified areas. They do not say where and what types of tanks. It could have been T-34s in the Sixth Guards Army area….or it could not be. They could have been deployed together or scattered.

There are a few reports of dug-in T-34s on 4 and 5 July 1943.

Guenther Baer, II Battalion of the LSSAH Tank Regiment, reports for the 4th of July, the pre-battle evening clearing attack on the Soviet outpost line that:

We also came upon scattered dug-in T-34s, who were then quickly disabled by our own tanks. (page 282…interview was done in 1999 by MG Dieter Brand).

Lt. Franz-Joachim von Rodde, an adjutant with the 6th Panzer Regiment, 3rd Panzer Division reports that:

That evening [5 July]…penetrated all the way to a small village [Krasnyii Pochinok] along a narrow front line and staggered towards the rear. The village itself could not be taken in time, though. Here we encountered T-34s dug-in up to their turrets for the first time. (page 367…interview was done in 1999 by MG Dieter Brand).

As I note on page 368:

Lt. Rodde’s memory of T-34s dug-in around Krasnyii Pochinok cannot be confirmed. The Soviet 245th Tank Regiment did not have T-34s. The nearest forces with T-34s would be the 59th and 60th Tank Regiment attached to the Fortieth Army. While these forces may well have been in the area (as this is not the only report of tanks we have on the front line of the 71st Guard Rifle Division, 67th Guards Rifle Division, or the Fortieth Army units), we have not accounts of them being there in the Soviet records.

Just to continue Rodde’s quote:

This was another measure hitherto unknown. These dug-in tanks were very dangerous. They were camouflaged extremely well–as usual with the Russians–and could only be reconnoitered once they opened fire. They usually fired at short range so as to have a maximum chance of hitting something.

Then there also the reports of dug-in tanks from Alfred Rubbel, 503rd Heavy Panzer (Tiger) Battalion, in the area where the 6th Panzer Division was attacking on the 5th, but this is out of the area of our concern (see page 403). Still just to quote:

Our Tiger company suffered the first losses as well. For the first time we saw dug-in enemy tanks in this sector. In a way this was a surprise as that was a use of tanks not at all typical. There dug-in tanks were firing with great precision from their position and were thus very dangerous for us. On that day alone, we have four losses due to enemy fire, which could all be recovered but nevertheless represented the highest number of losses in one day of battle we had to absorb during the entire operation.

Those tanks were most likely from the Soviet 262nd Tank Regiment, which started the battle with 22 KV-1s.

So we have reports of dug-in T-34s in front of the LSSAH Division and in front of 3rd Panzer Division. These are two widely separated locations. So it is distinctly possible that the SS Panzer Corps could have encountered 6-9 dug-in T-34s. This is still considerably less than what they claim, but probably there is some basis to their claims. Still, it would appear that they, or subsequent authors, either over-claimed or credited every tanks as destroyed as being a T-34, even though most were not.

Hard to sort it out 75 years after the fact…..but it is clear that many of the published claims for 5 July 1943 are not correct.

Today’s edition of TDI Friday Read is a roundup of posts by TDI President Christopher Lawrence exploring the details of tank combat between German and Soviet forces

Today’s edition of TDI Friday Read is a roundup of posts by TDI President Christopher Lawrence exploring the details of tank combat between German and Soviet forces