The third and last of three recent articles from William (Chip) Sayers. The conclusions are his:

——-

Wargaming 101 – Sayers vs. The US Navy

Early in the Reagan Administration, his Secretary of the Navy, John Lehman, adopted “The Maritime Strategy,” a doctrine that would send the US Navy aggressively into the face of the Soviet Union in the case of general war. Since the late 1930s, navies had been circumspect in sending their capital ships into the range of land-based airpower. The wisdom of this reticence was most spectacularly demonstrated two days after Pearl Harbor when the Royal Navy’s battleship HMS Prince of Wales and battlecruiser HMS Repulse were sunk while underway on the open ocean by Japanese bombers based outside of Saigon.

But 40 years later, SECNAV Lehman was seemingly throwing the hard-learned lessons of history to the wind. His plan was to send US Navy carrier battlegroups (CVBGs) into waters menaced by Soviet land-based airpower in order to threaten enemy base areas with nuclear-capable bombers. Secretary Lehman believed by bringing the CVBGs in close, it would unnerve Moscow and throw them off their game, possibly forcing mistakes that would ease the pressure on the central front. Writing years after he left Government, Lehman went so far as to say that the Maritime Strategy was instrumental in bringing down the Soviet Union.[1]

My math saw it a bit differently. The average carrier air wing of the 1980s consisted of two fleet air defense squadrons with 12 F-14 Tomcats, each; two light attack squadrons with a total of 24 A-7 Corsair IIs (later replaced by F-18 Hornets), one attack squadron with 10 A-6 Intruders — the heavy punch of the fleet — a fixed-wing anti-submarine squadron with 10 S-3 Vikings, a rotary-wing anti-submarine squadron with 8 SH-3 Sea Kings and roughly 16-20 radar warning, electronic warfare, cargo, tanker and reconnaissance aircraft. The F-14 was specifically designed to protect the CVBG from Soviet Naval Aviation (AV-MF, or in English, SNA) bombers, though it was also the only aircraft capable of escorting for the carrier’s bombers until the F-18s gradually replaced the A-7s over the course of the 1980s. Depending on how one counts the F-14, about 45% of the air wing was dedicated to defense of the battle group. Put another way, disregarding operational readiness rates, a carrier could dispatch 34 bombers against enemy targets. Compare that to a USAF F-111 wing that could put up considerably more bombers with significantly greater range and load-carrying capacity. Secretary Lehman’s big stick didn’t look so big in that light.

The Soviet Union was a Continental power and has always looked at military force from that perspective. To the Soviet General Staff, the Soviet Navy was a supporting arm whose primary responsibility was to aid the Army in securing its flanks. As such, the Navy took a backseat to the Army and Strategic Rocket Forces when it came to resources and emphasis in planning. In reality, it wasn’t as simple as this: Khruschev’s emphasis of nuclear missile forces at the expense of conventional forces gave the Navy not only a strategic offensive mission with their Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missiles (SLBMs), but also an important and frequently overlooked mission of securing the sub patrol areas near Soviet home waters when the range of their SLBMs made that possible in the mid-1970s.

To secure these “bastion” areas, the Soviet Navy devoted powerful combined-arms forces to keep the US Navy at bay. First, the Soviets deployed the world’s largest submarine fleet, comprised of a large number of modern, nuclear attack submarines along with a huge number of (albeit, mostly old) diesel-electric boats, and the only dedicated anti-ship cruise missile (ASCM) submarines in any navy. The second leg of this triad was a fleet of “rocket” cruisers with large, long-range anti-ship cruise missiles capable of destroying any ship smaller than an aircraft carrier with a single hit, and a carrier with multiple hits. These missiles were very long-ranged (240-340nm) compared to Western counterparts and exploitation of that capability may have been problematic, but the Soviet fleet was betting that they could overcome the targeting difficulties inherent to over-the-horizon missile shots. These missiles were as large as small fighter aircraft and, in addition to carrying a very large armor-piercing warhead, would hit the target moving at several times the speed of sound. Given the basic physics formula of energy = mass x velocity2, they would not even require a warhead for most targets.

The big stick on this combined-arms team, however, was the bomber regiments of Soviet Naval Aviation. Each Soviet fleet had two or three medium bomber regiments of 24-30 aircraft, each. Tu-16/BADGERS could carry two anti-ship cruise missiles, while supersonic Tu-22M/BACKFIRES could carry one on long-range missions, or up to three closer to home. These Kh-22 (AS-4/KITCHEN) ASCMs were about 2/3rds the size of a MiG-21 fighter, but could fly at Mach 4.6 and 90,000 feet while carrying a 1,000kg warhead. The Backfire was the threat the F-14 was developed to counter and, as a single SNA regiment could launch as many as 90 KITCHENs at a CVBG, it is clear why the F-14 — capable of carrying up to six long-range AIM-54 Phoenix bomber killing missiles — and the later cruiser-based Aegis high-volume-of-firepower Surface-to-Air Missile (SAM) system had to be developed.

To illustrate the utility of wargames in analyzing how the enemy views his Courses of Action (COAs), I would cite an unusual example. During the research phase for his novel Red Storm Rising, Tom Clancy asked a couple of mutual friends to help him wargame a troop convoy crossing of the Atlantic, intended to be the centerpiece of the story. Larry Bond and Chris Carlson (now hugely successful novelists in their own right) used Larry’s naval miniatures wargame Harpoon to facilitate the study. They quickly found that the SNA bombers in repeated trials were running to a brick wall formed by a USAF squadron of F-15 Eagles based at Keflavik, Iceland. The SNA never got close to the convoy. It was shaping up to be a boring novel, when one of the team members (I’ve heard it was Chris, though he denies it) thought of mounting a Spetsnaz commando raid prior to H-Hour to take out the pesky Eagles. This story was so compelling, it ended up as a major plotline in the novel. And the rest, as they say, is history.

The idea that the Soviet Navy was planning to shoot through the Greenland-Iceland-UK Gap and sweep the North Atlantic of NATO seapower was never a part of Soviet doctrine and Tom Clancy’s wargame experience shows why it was unrealistic. If a small number of USAF fighters could unhinge the entire operation, what would happen with many times that number of F-14s and Aegis cruisers? What of the powerful and practiced US and UK submarine force? Harpoon ASCM-firing B-52s? The enemy gets a vote when considering COAs, and NATO had a mind-boggling array of options to foil such a move by the Soviet Northern Fleet at the bleeding edge of its capabilities. This view was completely at odds with Soviet doctrine, which had the Soviet Navy playing — as it had in WWII — a primarily defensive role in support of the Army and the SLBM force.[2]

Far from counter-punching the Soviet Navy, the Maritime Strategy proposed walking face-first into a well-prepared, multi-faceted defense. However, Secretary Lehman was himself a naval aviator and he wasn’t suicidal. He did have ideas on how to mitigate the SNA threat. One was the use of Norway’s Vestfjord to provide his CVBGs with cover.[3]

USS America in Vestfjord clearly showing how the mountains would block the line of sight of missile-carrying bombers until they were very close to the target. (USNI Proceedings)

USS America in Vestfjord clearly showing how the mountains would block the line of sight of missile-carrying bombers until they were very close to the target. (USNI Proceedings)

Vestfjord is created by the Lofoten Archipelago that forms the northern side of Ofotfjord at Narvik and extends about 100nm into the North Sea. The dramatic vertical relief provides an excellent radar shadow protecting ships operating in the deep waters close inshore from airborne radars searching from the north. If that were the only trick up the Soviet sleeve, hiding in Vestfjord’s radar shadow would provide extra time for the CVBG’s F-14s to whittle down the attacking bombers before they could achieve line of sight and launch their missiles. That wasn’t, however, the end of the story. In fact, it was just the beginning for me.

Over a period of about three years in the late 1980s, I participated in a number of wargames where this issue came up. As a Soviet Air Forces analyst, I brought a different perspective to the problem. Secretary Lehman was well aware of the threat SNA posed to his CVBGs, but he was undoubtedly unversed on Soviet Air Force (VVS) capabilities and formations, since it would not have been a factor for him until he sent the Navy into Vestfjord.

While duking it out with the Navy, I ran into a phenomenon well-known within the wargaming community where the Navy under no circumstances would allow one of their aircraft carriers to be portrayed as being sunk or even seriously damaged. In one exercise, I was told that an attack by 90 bombers had managed to slightly damage one catapult. In another, my pilots had mysteriously mistaken a Royal Navy jump-jet carrier for a US CVN four times its size. After taking major losses on that raid, I nonchalantly told the Blue Navy player that I would whistle up another bomber division (like we “had plenty more where that came from”) and go at it again, tomorrow. He winced and admitted to me that there wasn’t any point because they would never allow me to sink a carrier. I replied that I just wanted him to admit that out loud before I let it go.

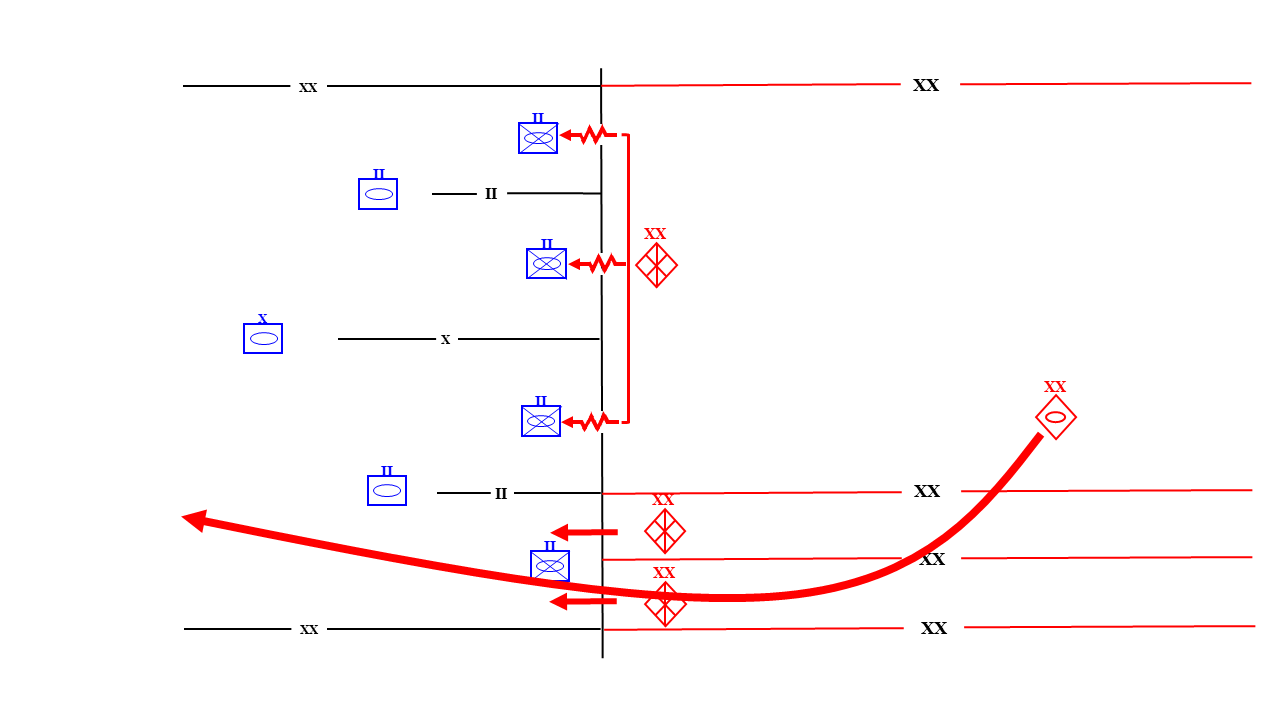

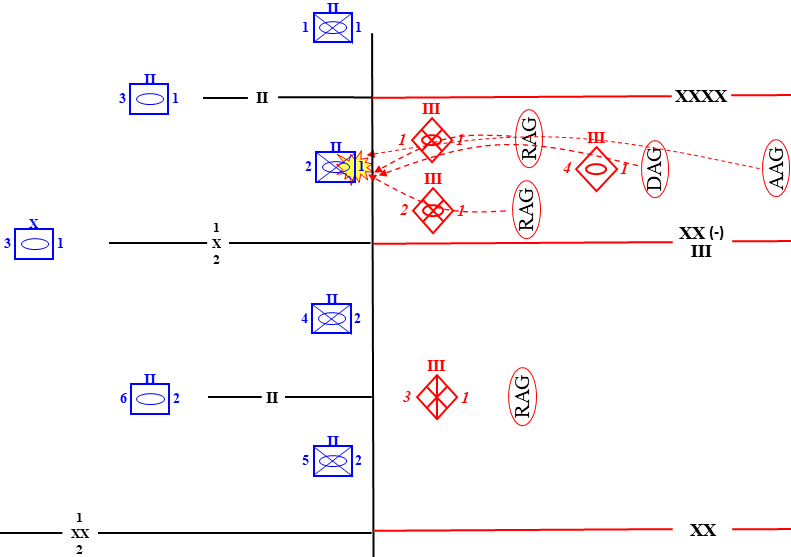

Yellow: SNA ASCM-carrying bombers fly from bases on and near the Kola, around the North Cape and down the coast of Norway. Large purple circle: Kh-22 300nm launch line. Small purple circle: Kh-22 67nm launch line (reduced by the radar shadow in Vestfjord). Blue: USN F-14 fleet defense fighters push north to intercept the SNA before they can get radar line-of-sight to the CVBG. Red: VVS Bomber Aviation Division uses the mountains to screen its attack on the CVBG.

Yellow: SNA ASCM-carrying bombers fly from bases on and near the Kola, around the North Cape and down the coast of Norway. Large purple circle: Kh-22 300nm launch line. Small purple circle: Kh-22 67nm launch line (reduced by the radar shadow in Vestfjord). Blue: USN F-14 fleet defense fighters push north to intercept the SNA before they can get radar line-of-sight to the CVBG. Red: VVS Bomber Aviation Division uses the mountains to screen its attack on the CVBG.

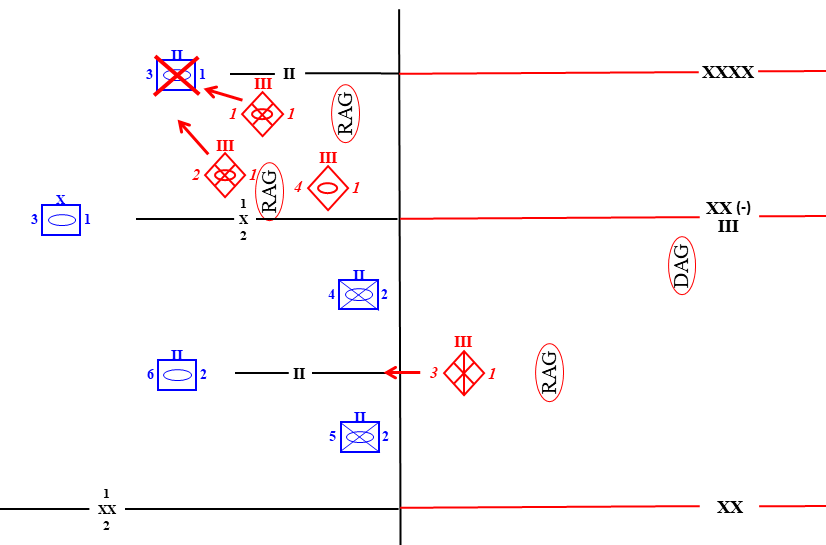

The final showdown came when I was called to the Pentagon and asked to give all the details of my tactics in a mano a mano combat with a Navy officer and a rather large crowd of onlookers. My final plan went like this: I sent a major SNA raid from the north to threaten the two-carrier CVBG hugging the southern slope of the mountains in Vestfjord. My opponent, knowing the broad strokes of my strategy, tried to hold back F-14s in reserve. However, he was quickly cut off by another Navy officer who said that the F-14s would have to “honor the threat” by committing the interceptors against the SNA bombers.

While the F-14s were tied up 100-200nm north of Vestfjord, I sent in a bomber aviation division with about 90 Su-24/FENCER light bombers armed with a pair of 1,500kg Laser-guided bombs apiece. This force went into Vestfjord in a long trail formation covered by Su-27/FLANKERS. My opponent raised the difficulties of finding the target ships, but I countered that in a trail formation, all the later aircraft need do would be to follow the smoke columns from the fires of shot down aircraft and damaged ships.

The FENCERS hugged the mountains so that their radars were looking out to sea for the CVBG, while the US radars were trying to pick out FENCERS from the radar clutter of the mountains behind them. What had been sauce for the goose had suddenly become sauce for the gander. The Navy knew from experience that picking out fighter aircraft from the mountains was a nasty challenge. This gave the VVS bombers a real chance to make it through to the target.

While nearly all modern warships lack any kind of significant armor, US Navy aircraft carriers are the exception. The Navy keeps the details close to their chest, but even if they don’t have conventional armor plate like a battleship, the use of fuel and water tankage can create a reasonable facsimile, while the sheer size of a carrier and the compartmentation available ensure that any damage is isolated and kept away from the vital areas of the ship. To do real harm takes a large bomb with real penetrative capability. Both of these are embodied in the 1,500kg bomb. Further, while dropping from low altitude — deck height or lower — the bomb would impact almost perpendicular to the side of the ship, ensuring maximum penetration. Laser guidance wouldn’t add too much to the equation, but it did give me an extra argument to deflect disputes about accuracy. With the bombs detonating inside the ship, there would be no danger from fragging one’s own aircraft and little danger to following planes, as well. A further advantage to dropping from such low altitude would be that it would be nearly impossible to mistake the target carrier with anything else — no other ship would tower over the bombers so they need only steer for the biggest object ahead of them.

Squirm as he might, my opponent was frustrated at every turn. Each idea he came up with was shot down by the onlookers. The Navy observers looked at our little desk-side exercise and could find no way out. They were finally forced to concede that their carriers were not invincible, after all. From that day to this, I haven’t heard the Navy talk about Vestfjord or taking on land-based air. My campaign may not have been what caused the Navy to rethink The Maritime Strategy, but it assuredly provided at least one nail in the coffin.

Naval wargaming is simple and straightforward when compared to wargaming ground combat. Naval warfare lends itself to mathematical fights between weapons systems. There are little, if any, terrain considerations and all the combatants can be discretely modeled. Further, there is little of the human element to be considered as most of the interactions are, in reality, controlled by computer. In contrast, a land battle has a nearly infinite number of interactions and the human factor is the most important single determinate of defeat — you defeat the enemy by breaking his will to stand his ground — while weapons are merely tools to get inside his head. Elsewhere in this blog, I have stated that I had $40 commercial wargames in my closet that could do a more realistic job than the Pentagon’s million-dollar computer models. The cost factor only grows larger with naval wargames.

Perhaps this is why the US Navy has traditionally invested in wargames: the inherent simplicity, clarity and believable results of naval wargames make them accessible and instructive. After WWII, Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz was asked if anything surprised him during the battles of the Pacific war. His answer, that only the Japanese use of Kamikaze tactics had not been foreseen and wargamed before the war ever began, is informative on the utility of naval wargaming. The US Naval War College continues to this day to run annual wargames with its students working on fleet problems with real-world relevance. The War College’s own website declared that, “Simulating complex war situations—from sea to space to cyber—builds analytical, strategic, and decision-making skills. Wargaming programming not only enriches our curriculum, but it also helps shape defense plans and policies for various commands and agencies.” Thus saith the Navy. The Air Force would agree. If we can get the Army in on it, we might have something of use to the nation.

[1] Zakheim, Dov S. and Lehman, John (2018) “Lehman’s Maritime Triumph,” Naval War College Review: Vol. 71 : No. 4 , Article 11. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol71/iss4/11.

[2] Watkins, James D. Admiral USN, The Maritime Strategy, US Naval Institute Proceedings, January 1986, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1986/january-supplement/maritime-strategy-0.

[3] Ibid.

——

His other recent and related articles are:

The Easy Button | Mystics & Statistics (dupuyinstitute.org)

Wargaming 101 – The 40-60-80 Games | Mystics & Statistics (dupuyinstitute.org)

Wargaming 101 – In the Bowels of the Pentagon with J-8 | Mystics & Statistics (dupuyinstitute.org)

Wargaming 101: The Bad Use of a Good Tool | Mystics & Statistics (dupuyinstitute.org)

Wargaming 101: A Tale of Two Forces | Mystics & Statistics (dupuyinstitute.org)

He is doing a presentation at HAAC on Day 2 (Wednesday, Oct. 18) on Wargaming 101: Schedule for the Second Historical Analysis Annual Conference (HAAC), 17-19 October 2023 | Mystics & Statistics (dupuyinstitute.org)