Military History and Validation of Combat Models

A Presentation at MORS Mini-Symposium on Validation, 16 Oct 1990

By Trevor N. Dupuy

In the operations research community there is some confusion as to the respective meanings of the words “validation” and “verification.” My definition of validation is as follows:

“To confirm or prove that the output or outputs of a model are consistent with the real-world functioning or operation of the process, procedure, or activity which the model is intended to represent or replicate.”

In this paper the word “validation” with respect to combat models is assumed to mean assurance that a model realistically and reliably represents the real world of combat. Or, in other words, given a set of inputs which reflect the anticipated forces and weapons in a combat encounter between two opponents under a given set of circumstances, the model is validated if we can demonstrate that its outputs are likely to represent what would actually happen in a real-world encounter between these forces under those circumstances

Thus, in this paper, the word “validation” has nothing to do with the correctness of computer code, or the apparent internal consistency or logic of relationships of model components, or with the soundness of the mathematical relationships or algorithms, or with satisfying the military judgment or experience of one individual.

True validation of combat models is not possible without testing them against modern historical combat experience. And so, in my opinion, a model is validated only when it will consistently replicate a number of military history battle outcomes in terms of: (a) Success-failure; (b) Attrition rates; and (c) Advance rates.

“Why,” you may ask, “use imprecise, doubtful, and outdated history to validate a modem, scientific process? Field tests, experiments, and field exercises can provide data that is often instrumented, and certainly more reliable than any historical data.”

I recognize that military history is imprecise; it is only an approximate, often biased and/or distorted, and frequently inconsistent reflection of what actually happened on historical battlefields. Records are contradictory. I also recognize that there is an element of chance or randomness in human combat which can produce different results in otherwise apparently identical circumstances. I further recognize that history is retrospective, telling us only what has happened in the past. It cannot predict, if only because combat in the future will be fought with different weapons and equipment than were used in historical combat.

Despite these undoubted problems, military history provides more, and more accurate information about the real world of combat, and how human beings behave and perform under varying circumstances of combat, than is possible to derive or compile from arty other source. Despite some discrepancies, patterns are unmistakable and consistent. There is always a logical explanation for any individual deviations from the patterns. Historical examples that are inconsistent, or that are counter-intuitive, must be viewed with suspicion as possibly being poor or false history.

Of course absolute prediction of a future event is practically impossible, although not necessarily so theoretically. Any speculations which we make from tests or experiments must have some basis in terms of projections from past experience.

Training or demonstration exercises, proving ground tests, field experiments, all lack the one most pervasive and most important component of combat: Fear in a lethal environment. There is no way in peacetime, or non-battlefield, exercises, test, or experiments to be sure that the results are consistent with what would have been the behavior or performance of individuals or units or formations facing hostile firepower on a real battlefield.

We know from the writings of the ancients (for instance Sun Tze—pronounced Sun Dzuh—and Thucydides) that have survived to this day that human nature has not changed since the dawn of history. The human factor the way in which humans respond to stimuli or circumstances is the most important basis for speculation and prediction. What about the “scientific” approach of those who insist that we cart have no confidence in the accuracy or reliability of historical data, that it is therefore unscientific, and therefore that it should be ignored? These people insist that only “scientific” data should be used in modeling.

In fact, every model is based upon fundamental assumptions that are intuitive and unprovable. The first step in the creation of a model is a step away from scientific reality in seeking a basis for an unreal representation of a real phenomenon. I have shown that the unreality is perpetuated when we use other imitations of reality as the basis for representing reality. History is less than perfect, but to ignore it, and to use only data that is bound to be wrong, assures that we will not be able to represent human behavior in real combat.

At the risk of repetition, and even of protesting too much, let me assure you that I am well aware of the shortcomings of military history:

The record which is available to us, which is history, only approximately reflects what actually happened. It is incomplete. It is often biased, it is often distorted. Even when it is accurate, it may be reflecting chance rather than normal processes. It is neither precise nor consistent. But, it provides more, and more accurate, information on the real world of battle than is available from the most thoroughly documented field exercises, proving ground less, or laboratory or field experiments.

Military history is imperfect. At best it reflects the actions and interactions of unpredictable human beings. We must always realize that a single historical example can be misleading for either of two reasons: (1) The data may be inaccurate, or (2) The data may be accurate, but untypical.

Nevertheless, history is indispensable. I repeat that the most pervasive characteristic of combat is fear in a lethal environment. For all of its imperfections, military history and only military history represents what happens under the environmental condition of fear.

Unfortunately, and somewhat unfairly, the reported findings of S.L.A. Marshall about human behavior in combat, which he reported in Men Against Fire, have been recently discounted by revisionist historians who assert that he never could have physically performed the research on which the book’s findings were supposedly based. This has raised doubts about Marshall’s assertion that 85% of infantry soldiers didn’t fire their weapons in combat in World War ll. That dramatic and surprising assertion was first challenged in a New Zealand study which found, on the basis of painstaking interviews, that most New Zealanders fired their weapons in combat. Thus, either Americans were different from New Zealanders, or Marshall was wrong. And now American historians have demonstrated that Marshall had had neither the time nor the opportunity to conduct his battlefield interviews which he claimed were the basis for his findings.

I knew Marshall, moderately well. I was fully as aware of his weaknesses as of his strengths. He was not a historian. I deplored the imprecision and lack of documentation in Men Against Fire. But the revisionist historians have underestimated the shrewd journalistic assessment capability of “SLAM” Marshall. His observations may not have been scientifically precise, but they were generally sound, and his assessment has been shared by many American infantry officers whose judgements l also respect. As to the New Zealand study, how many people will, after the war, admit that they didn’t fire their weapons?

Perhaps most important, however, in judging the assessments of SLAM Marshall, is a recent study by a highly-respected British operations research analyst, David Rowland. Using impeccable OR methods Rowland has demonstrated that Marshall’s assessment of the inefficient performance, or non-performance, of most soldiers in combat was essentially correct. An unclassified version of Rowland’s study, “Assessments of Combat Degradation,” appeared in the June 1986 issue of the Royal United Services Institution Journal.

Rowland was led to his investigations by the fact that soldier performance in field training exercises, using the British version of MILES technology, was not consistent with historical experience. Even after allowances for degradation from theoretical proving ground capability of weapons, defensive rifle fire almost invariably stopped any attack in these field trials. But history showed that attacks were often in fact, usually successful. He therefore began a study in which he made both imaginative and scientific use of historical data from over 100 small unit battles in the Boer War and the two World Wars. He demonstrated that when troops are under fire in actual combat, there is an additional degradation of performance by a factor ranging between 10 and 7. A degradation virtually of an order of magnitude! And this, mind you, on top of a comparable built-in degradation to allow for the difference between field conditions and proving ground conditions.

Not only does Rowland‘s study corroborate SLAM Marshall’s observations, it showed conclusively that field exercises, training competitions and demonstrations, give results so different from real battlefield performance as to render them useless for validation purposes.

Which brings us back to military history. For all of the imprecision, internal contradictions, and inaccuracies inherent in historical data, at worst the deviations are generally far less than a factor of 2.0. This is at least four times more reliable than field test or exercise results.

I do not believe that history can ever repeat itself. The conditions of an event at one time can never be precisely duplicated later. But, bolstered by the Rowland study, I am confident that history paraphrases itself.

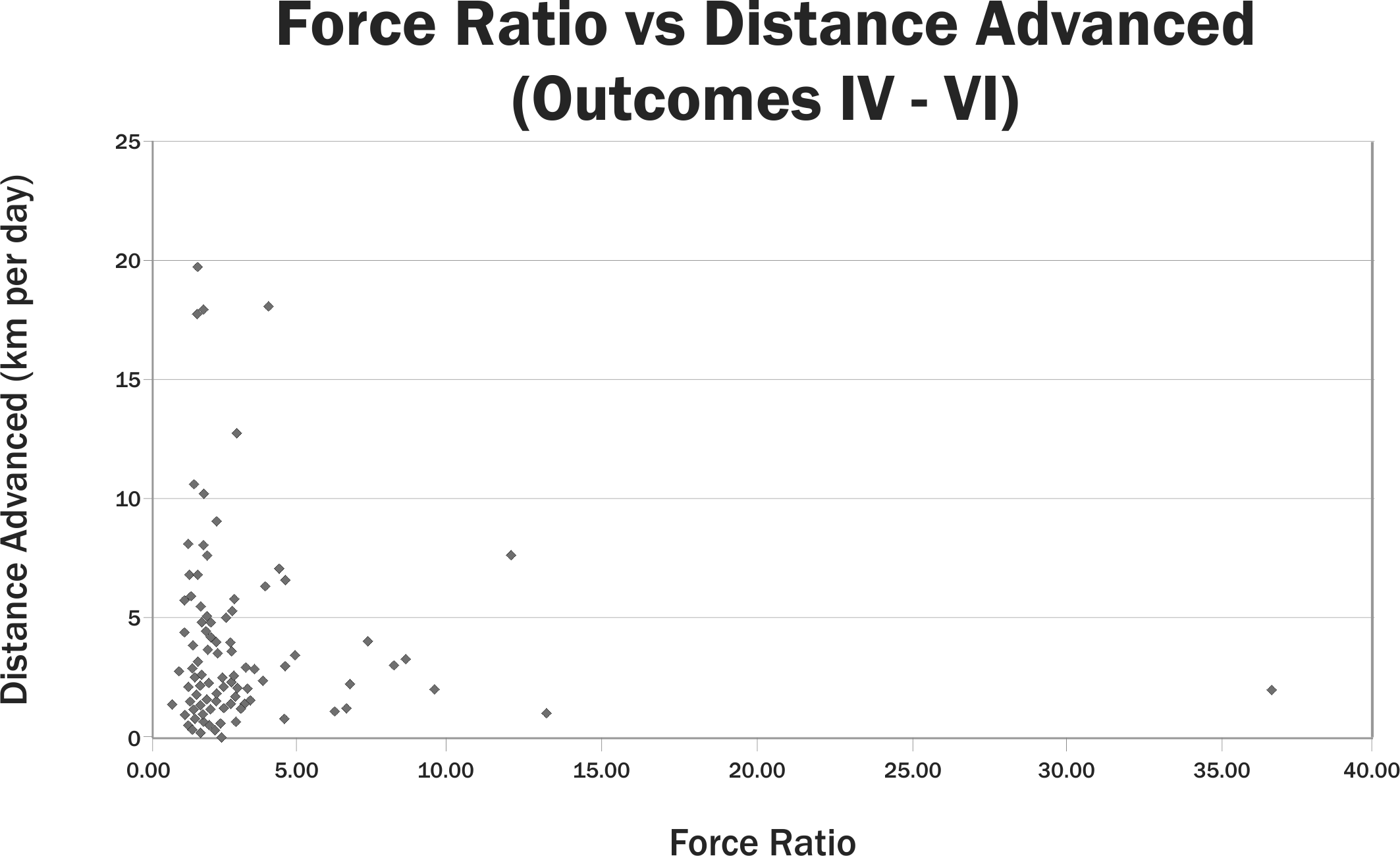

If large bodies of historical data are compiled, the patterns are clear and unmistakable, even if slightly fuzzy around the edges. Behavior in accordance with this pattern is therefore typical. As we have already agreed, sometimes behavior can be different from the pattern, but we know that it is untypical, and we can then seek for the reason, which invariably can be discovered.

This permits what l call an actuarial approach to data analysis. We can never predict precisely what will happen under any circumstances. But the actuarial approach, with ample data, provides confidence that the patterns reveal what is to happen under those circumstances, even if the actual results in individual instances vary to some extent from this “norm” (to use the Soviet military historical expression.).

It is relatively easy to take into account the differences in performance resulting from new weapons and equipment. The characteristics of the historical weapons and the current (or projected) weapons can be readily compared, and adjustments made accordingly in the validation procedure.

In the early 1960s an effort was made at SHAPE Headquarters to test the ATLAS Model against World War II data for the German invasion of Western Europe in May, 1940. The first excursion had the Allies ending up on the Rhine River. This was apparently quite reasonable: the Allies substantially outnumbered the Germans, they had more tanks, and their tanks were better. However, despite these Allied advantages, the actual events in 1940 had not matched what ATLAS was now predicting. So the analysts did a little “fine tuning,” (a splendid term for fudging). Alter the so-called adjustments, they tried again, and ran another excursion. This time the model had the Allies ending up in Berlin. The analysts (may the Lord forgive them!) were quite satisfied with the ability of ATLAS to represent modem combat. (Or at least they said so.) Their official conclusion was that the historical example was worthless, since weapons and equipment had changed so much in the preceding 20 years!

As I demonstrated in my book, Options of Command, the problem was that the model was unable to represent the German strategy, or to reflect the relative combat effectiveness of the opponents. The analysts should have reached a different conclusion. ATLAS had failed validation because a model that cannot with reasonable faithfulness and consistency replicate historical combat experience, certainly will be unable validly to reflect current or future combat.

How then, do we account for what l have said about the fuzziness of patterns, and the fact that individual historical examples may not fit the patterns? I will give you my rules of thumb:

- The battle outcome should reflect historical success-failure experience about four times out of five.

- For attrition rates, the model average of five historical scenarios should be consistent with the historical average within a factor of about 1.5.

- For the advance rates, the model average of five historical scenarios should be consistent with the historical average within a factor of about 1.5.

Just as the heavens are the laboratory of the astronomer, so military history is the laboratory of the soldier and the military operations research analyst. The scientific basis for both astronomy and military science is the recording of the movements and relationships of bodies, and then analysis of those movements. (In the one case the bodies are heavenly, in the other they are very terrestrial.)

I repeat: Military history is the laboratory of the soldier. Failure of the analyst to use this laboratory will doom him to live with the scientific equivalent of Ptolomean astronomy, whereas he could use the evidence available in his laboratory to progress to the military science equivalent of Copernican astronomy.