The Division Level Engagement Data Base (DLEDB) is one of eight data bases that make up our DuWar suite of databases: See http://www.dupuyinstitute.org/dbases.htm This data base, of 752 engagements, is described in depth at: http://www.dupuyinstitute.org/data/dledb.htm

It now consists of 752 engagements from 1904 to 1991. It was originally created in 2000-2001 by us independent of any government contracts (so as to ensure it was corporate proprietary). We then used it as an instrumental part of the our Enemy Prisoner of War studies and then our three Urban Warfare studies.

Below is a list of wars/campaigns the engagements are pulled from:

Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905): 3 engagements

Balkan Wars (1912-1913): 1 engagement

World War I (1914-1918): 25 engagements

…East Prussia (1914): 1

…Gallipoli (1915): 2

…Mesopotamia (1915): 2

…1st & 2nd Artois (1915): 7

…Loos (1915): 2

…Somme (1916): 2

…Mesopotamia (1917): 1

…Palestine (1917): 2

…Palestine (1918): 1

…US engagements (1918): 5

World War II (1939-1945): 657 engagements

…Western Front: 295

……France (1940): 2

……North Africa (1941): 5

……Crete (1941): 1

……Tunisia (1943): 5

……Italian Campaign (1943-1944): 141

……France (1944): 61

…,,,Aachen (1944): 23

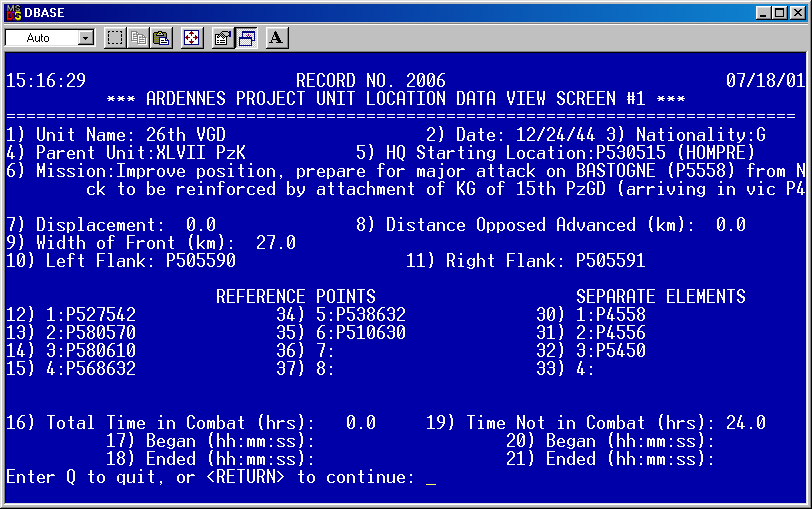

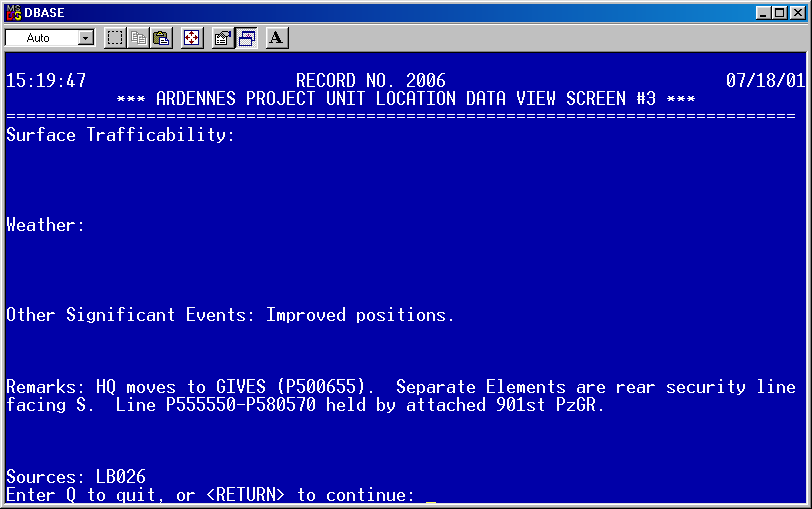

……Ardennes (1944-1945): 57

…Eastern Front: 267

……Eastern Front (1943-1945): 11

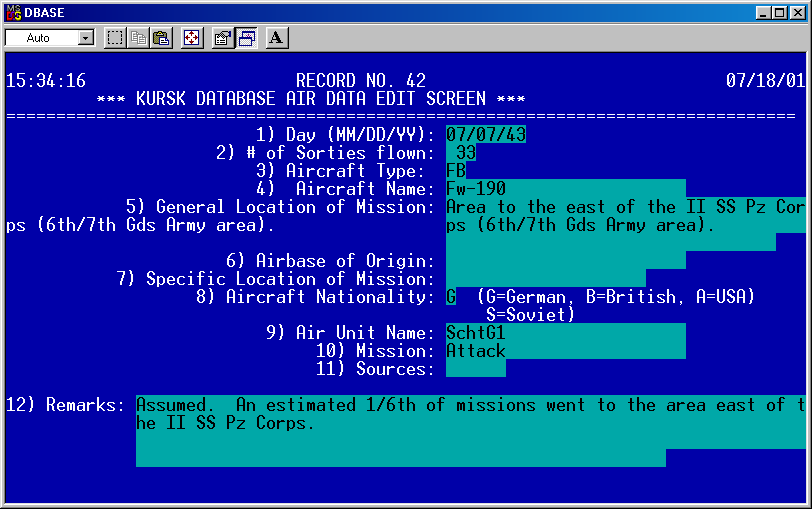

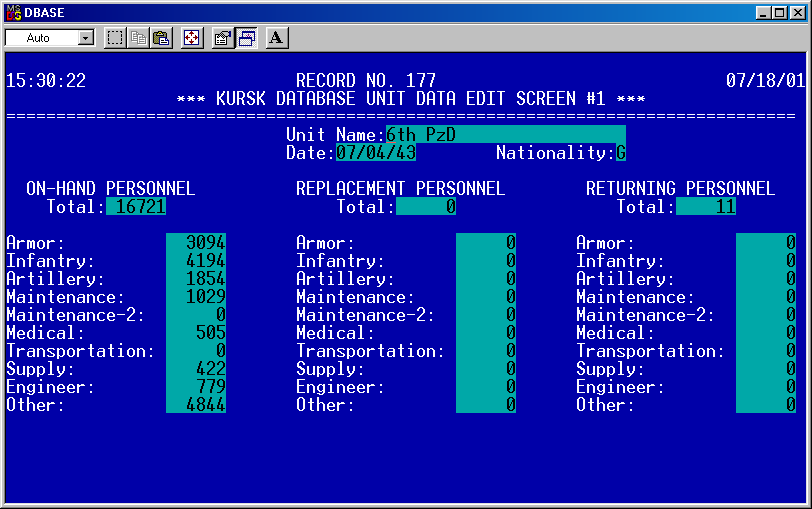

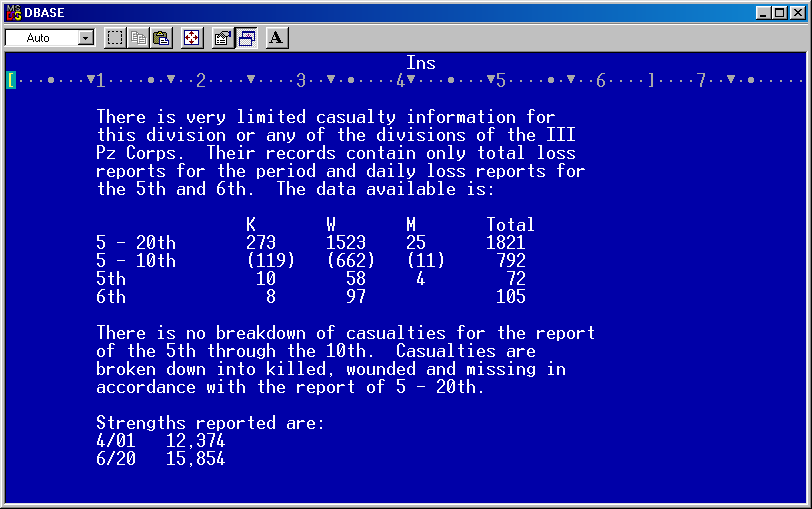

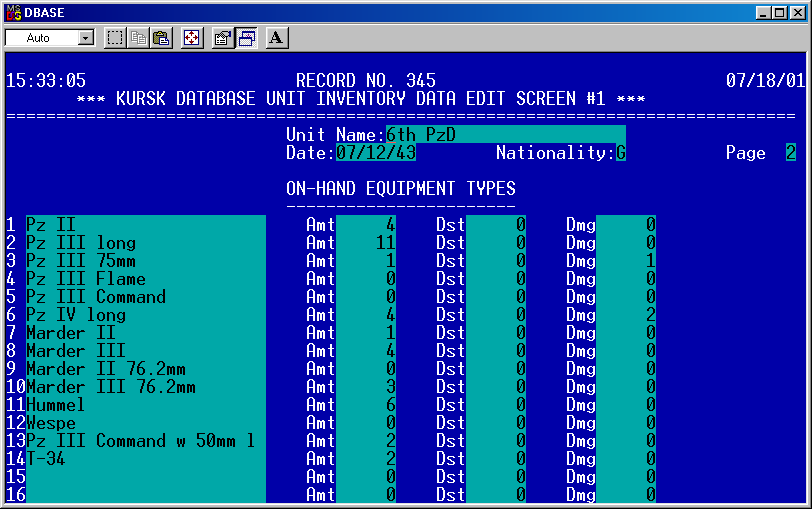

…….Kursk (1943): 192

……Kharkov (1943): 64

…Pacific Campaign: 95

…….Manchuria (1938): 1

…….Malayan Campaign (1941): 1

…….Phillipines (1942): 1

…….Islands (1944-1945): 4

…….Okinawa (1945): 27

…….Manila (1945): 61

Arab-Israeli Wars (1956-1973): 51 engagements

…1956: 2

…1967: 16

…1968: 1

…1973: 32

Gulf War (1991): 15 engagements

Now our revised version of the earlier Land Warfare Data Base (LWDB) of 605 engagements had more World War I engagements. But some of these engagements had over a hundred of thousand men on a side and some lasted for months. It was based upon how the battles were defined at the time; but was really not relevant for use in a division-level database. So, we shuffled them off to something called the Large Action Data Base (LADB), were 55 engagements have sat, unused, since then. Some actions in the original LWDB were smaller than division-level. These made up the core of our battalion-level and company-level data bases.

The Italian Campaign Engagements were the original core of this database. An earlier version of the data base has only 76 engagements from Italy in them (around year 2000). We then expanded, corrected and revised them. So the database still has 40 of the original engagements, 22 were revised, and the rest (79) are new.

The original LWDB was used for parts of Trevor Dupuy’s book Understanding War. The DLEDB was a major component of my book War by Numbers.

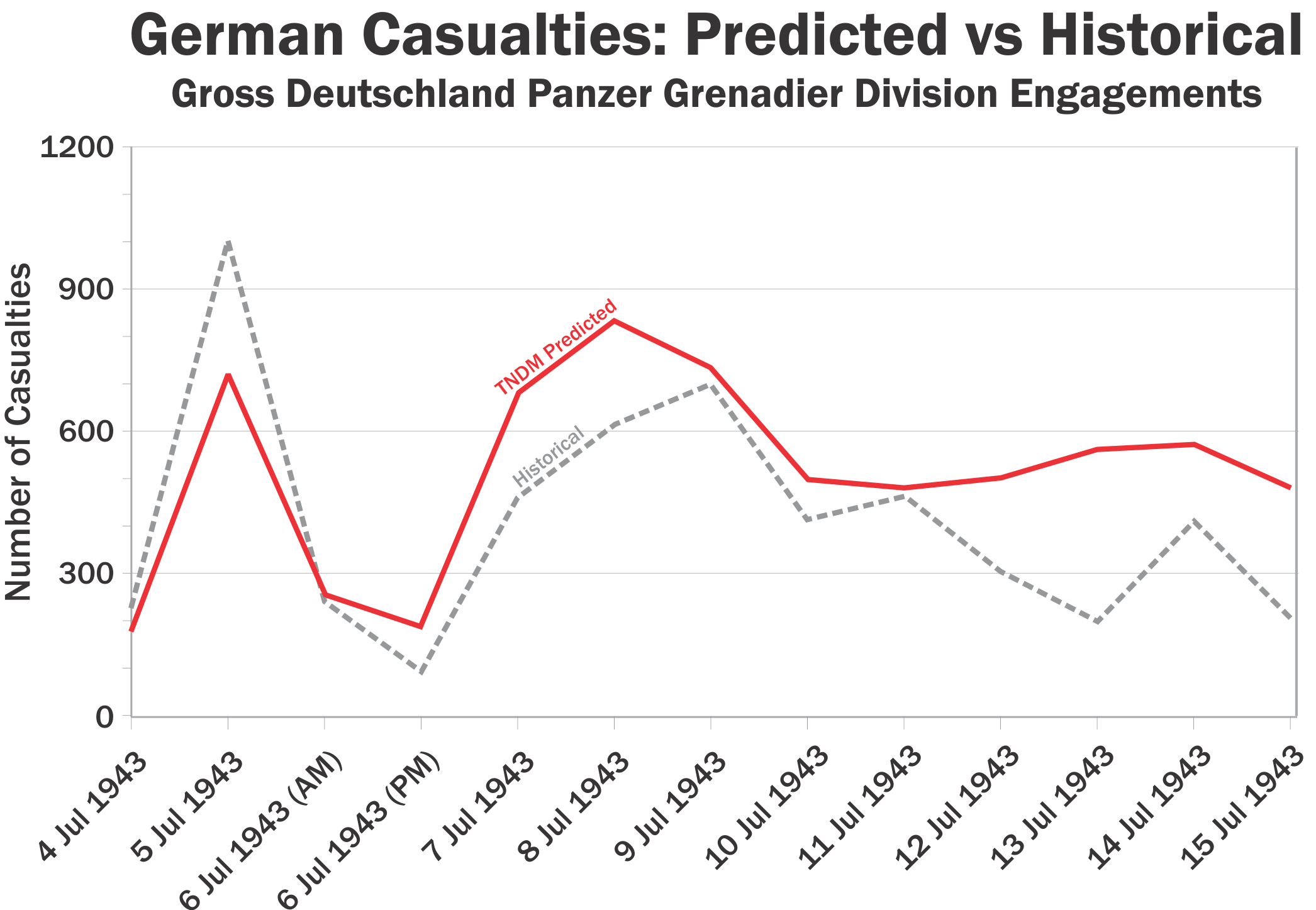

As can be seen, it is possible to use this database for model development and/or validation. One could start by developing/testing the model to the 141 Italian Campaign engagements, and then further develop it by testing it to the 141 campaigns from France and the Battle of the Bulge. And then, to test the human factors elements of your models (which if you are modeling warfare I would hope you would have), one could then test it to the 267 division-level engagements on the Eastern Front. Then move forward in time with the 51 engagements from the Arab-Israeli Wars and the 15 engagements from the Gulf War. There is not a lack of data available for model development or model testing. It is, of course, a lot of work; and lately it seems that the industry has been more concerned about making sure their models have good graphics.

Just to beat a dead horse, we remind you of this post that annoyed several people over at TRADOC (the U.S. Army’s Training and Doctrine Command):

Finally, it is possible to examine changes in warfare over time. This is useful to understand it one is looking at changes in warfare in the future. The DLEDB covers 88 years of warfare. We also have the Battles Data Base (BaDB) of 243 battles from 1600-1900. It is described here: http://www.dupuyinstitute.org/data/badb.htm

Next I will describe our battalion-level and company-level databases.

The December 2018 issue of

The December 2018 issue of