So we created three campaign databases. One of the strangest arguments I have heard against doing validations or testing combat models to historical data, is that this is only one outcome from history. So you don’t know if model is in error or if this was a unusual outcome to the historical event. Someone described it as the N=1 argument. There are lots of reasons why I am not too impressed with this argument that I may enumerate in a later blog post. It certainly might apply to testing the model to just one battle (like the Battle of 73 Easting in 1991), but these are weeks-long campaign databases with hundreds of battles. One can test the model to these hundreds of points in particular in addition to testing it to the overall result.

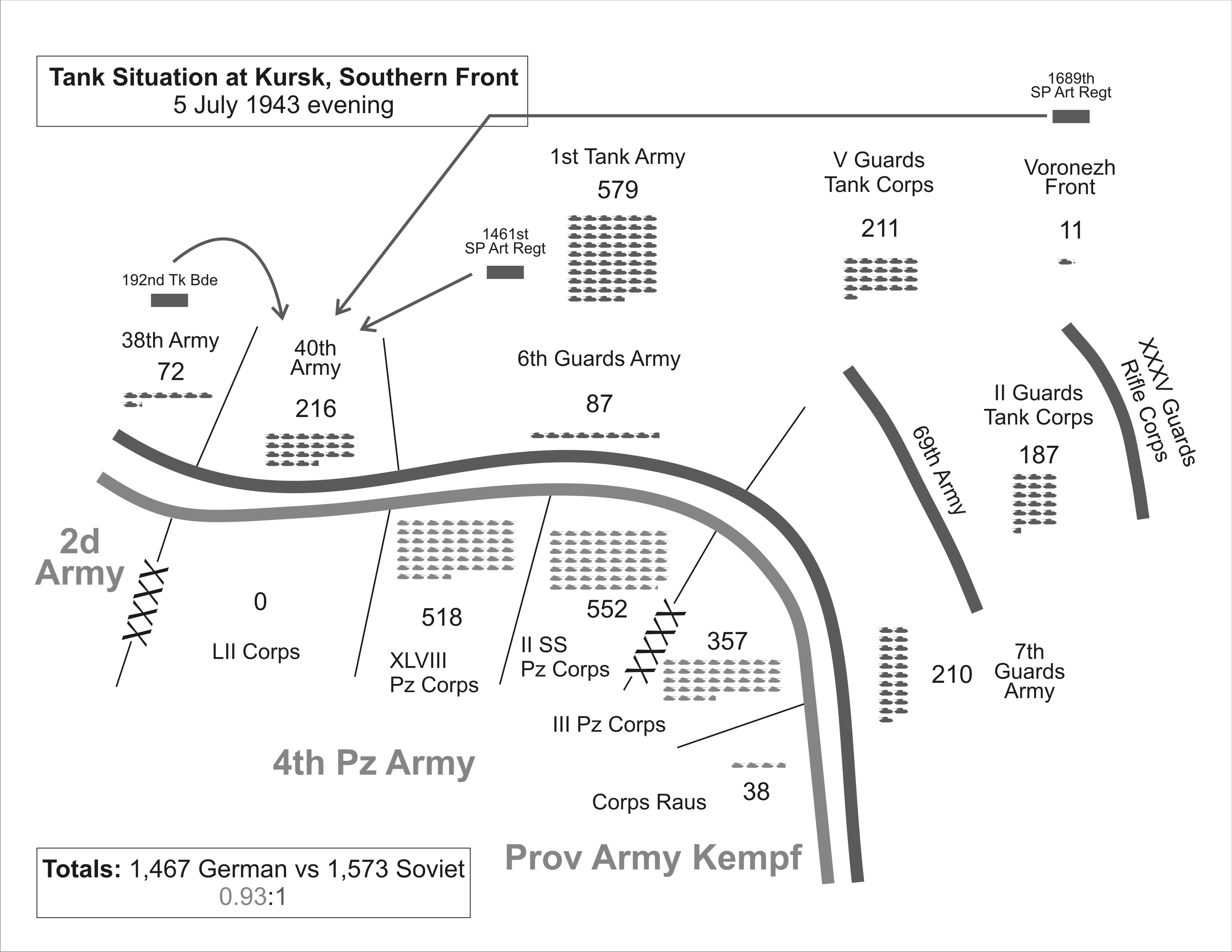

In the case of the Kursk Data Base (KDB), we have actually gone through the data base and created from it 192 division-level engagements. This covers every single combat action by every single division during the two week offensive around Belgorod. Furthermore, I have listed each and every one of these as an “engagement sheet’ in my book on Kursk. The 192 engagement sheets are a half-page or page-long tabulation of the strengths and losses for each engagement for all units involved. Most sheets cover one day of battle. It took considerable work to assemble these. First one had to figure out who was opposing whom (especially as unit boundaries never match) and then work from there. So, if someone wants to test a model or model combat or do historical analysis, one could simply assemble a database from these 192 engagements. If one wanted more details on the engagements, there are detailed breakdowns of the equipment in the Kursk Data Base and detailed descriptions of the engagements in my Kursk book. My new Prokhorovka book (release date 1 June), which only covers the part of the southern offensive around Prokhorovka from the 9th of July, has 76 of those engagements sheets. Needless to say, these Kursk engagements also make up 192 of the 752 engagements in our DLEDB (Division Level Engagement Data Base). A picture of that database is shown at the top of this post.

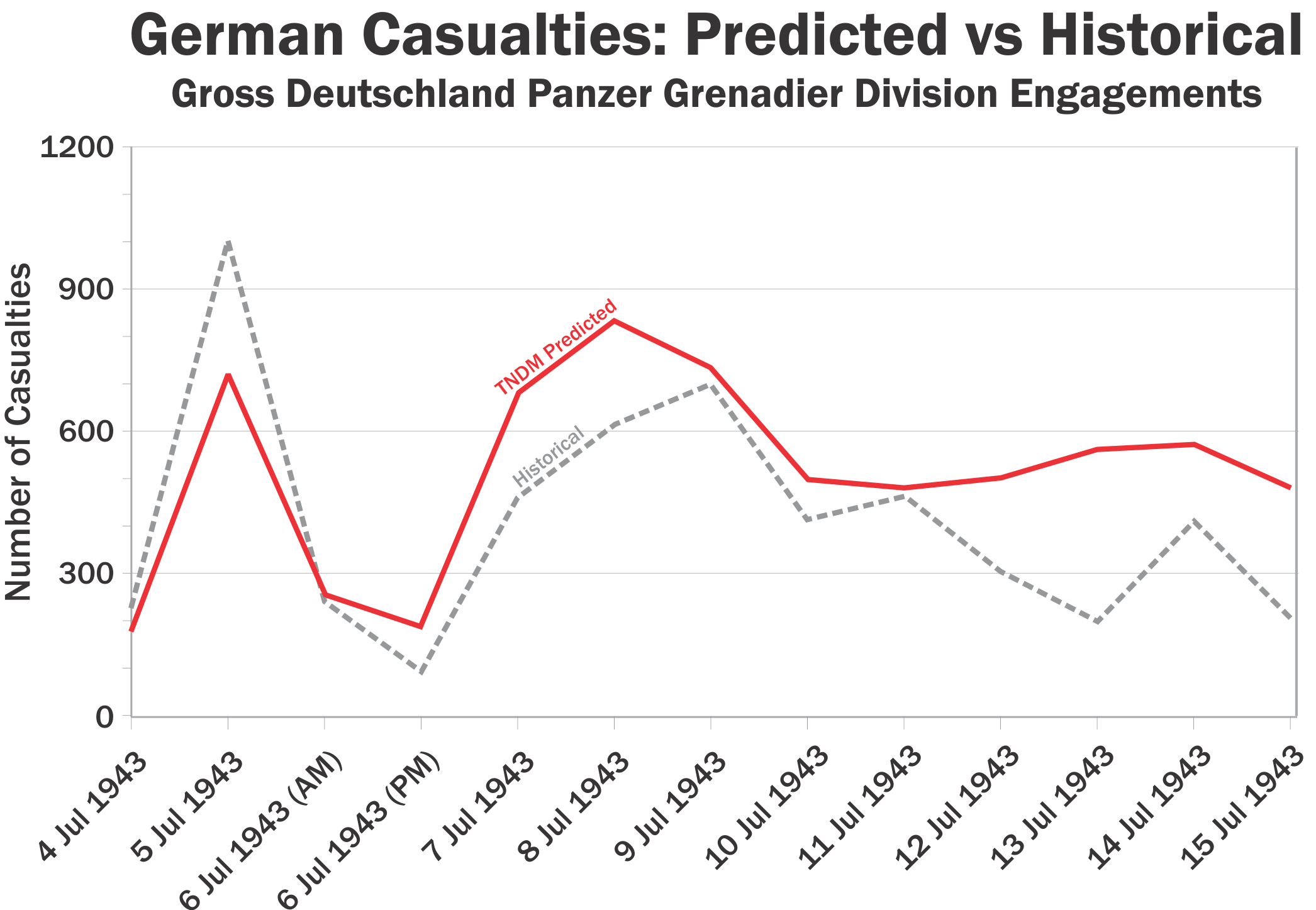

So, if you are conducting a validation to the campaign, take a moment and check the results to each division to each day. In the KDB there were 17 divisions on the German side, and 37 rifle divisions and 10 tank and mechanized corps (a division-sized unit) on the Soviet side. The data base covers 15 days of fighting. So….there are around 900 points of daily division level results to check the results to. I drawn your attention to this graph:

There are a number of these charts in Chapter 19 of my book War by Numbers. Also see:

The Ardennes database is even bigger. There was one validation done by CAA (Center for Army Analysis) of its CEM model (Concepts Evaluation Model) using the Ardennes Campaign Simulation Data Bases (ACSDB). They did this as an overall comparison to the campaign. So they tracked the front line trace at the end of the battle, and the total tank losses during the battle, ammunition consumption and other events like that. They got a fairly good result. What they did not do was go into the weeds and compare the results of the engagements. CEM relies on inputs from ATCAL (Attrition Calculator) which are created from COSAGE model runs. So while they tested the overall top-level model, they really did not test ATCAL or COSAGE, the models that feed into it. ATCAL and COSAGE I gather are still in use. In the case of Ardennes you have 36 U.S. and UK divisions and 32 German divisions and brigades over 32 days, so over 2,000 division days of combat. That is a lot of data points to test to.

Now we have not systematically gone through the ACSDB and assembled a record for every single engagement there. There would probably be more than 400 such engagements. We have assembled 57 engagements from the Battle of the Bulge for our division-level database (DLEDB). More could be done.

Finally, during our Battle of Britain Data Base effort, we recommended developing an air combat engagement database of 120 air-to-air engagements from the Battle of Britain. We did examine some additional mission specific data for the British side derived from the “Form F” Combat Reports for the period 8-12 August 1940. This was to demonstrate the viability of developing an engagement database from the dataset. So we wanted to do something similar for the air combat that we had done with division-level combat. An air-to-air engagement database would be very useful if you are developing any air campaign wargame. This unfortunately was never done by us as the project (read: funding) ended.

As it is we actually have three air campaign databases to work from, the Battle of Britain data base, the air component of the Kursk Data Base, and the air component of the Ardennes Campaign Simulation Data Base. There is a lot of material to work from. All it takes it a little time and effort.

I will discuss the division-level data base in more depth in my next post.