What we have listed in the previous articles is what we consider the six best databases to use for validation. The Ardennes Campaign Simulation Data Base (ACSDB) was used for a validation effort by CAA (Center for Army Analysis). The Kursk Data Base (KDB) was never used for a validation effort but was used, along with Ardennes, to test Lanchester equations (they failed).

The Battle of Britain Data Base to date has not been used for anything that we are aware of. As the program we were supporting was classified, then they may have done some work with it that we are not aware of, but I do not think that is the case.

Our three battles databases, the division-level data base, the battalion-level data base and the company-level data base, have all be used for validating our own TNDM (Tactical Numerical Deterministic Model). These efforts have been written up in our newsletters (here: http://www.dupuyinstitute.org/tdipub4.htm) and briefly discussed in Chapter 19 of War by Numbers. These are very good databases to use for validation of a combat model or testing a casualty estimation methodology. We have also used them for a number of other studies (Capture Rate, Urban Warfare, Lighter-Weight Armor, Situational Awareness, Casualty Estimation Methodologies, etc.). They are extremely useful tools analyzing the nature of conflict and how it impacts certain aspects. They are, of course, unique to The Dupuy Institute and for obvious business reasons, we do keep them close hold.

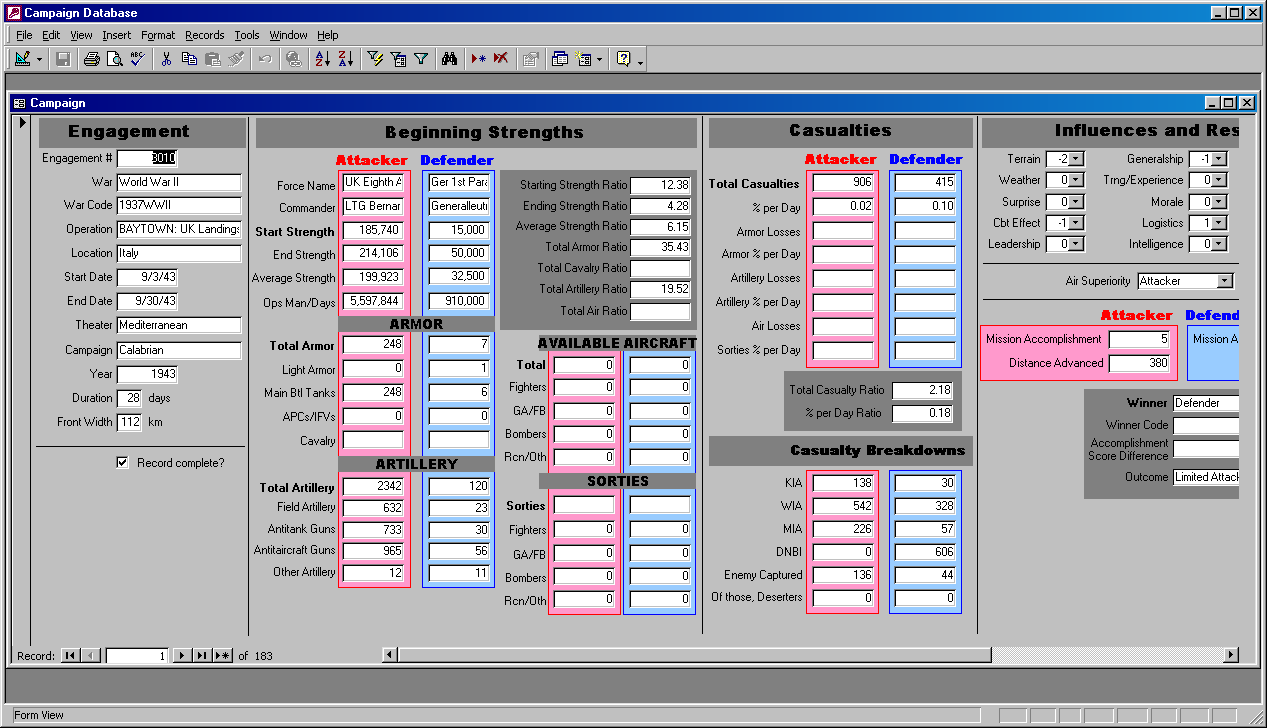

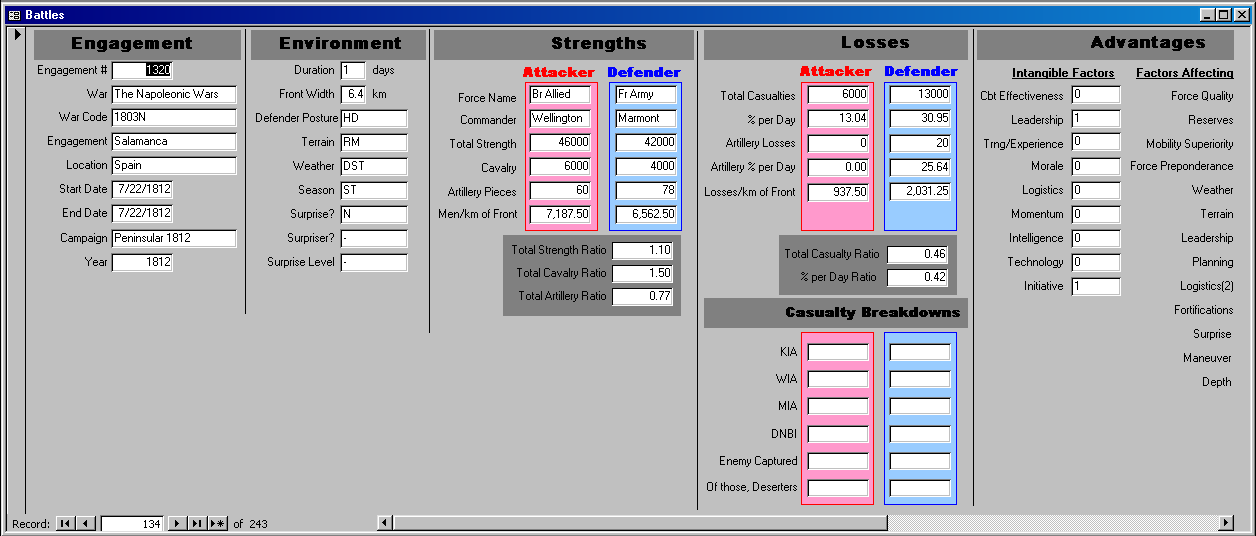

We do have a number of other database that have not been used as much. There is a list of 793 conflicts from 1898-1998 that we have yet to use for anything (the WACCO – Warfare, Armed Conflict and Contingency Operations database). There is the Campaign Data Base (CaDB) of 196 cases from 1904 to 1991, which was used for the Lighter Weight Armor study. There are three databases that are mostly made of cases from the original Land Warfare Data Base (LWDB) that did not fit into our division-level, battalion-level, and company-level data bases. They are the Large Action Data Base (LADB) of 55 cases from 1912-1973, the Small Action Data Base (SADB) of 5 cases and the Battles Data Base (BaDB) of 243 cases from 1600-1900. We have not used these three database for any studies, although the BaDB is used for analysis in War by Numbers.

Finally, there are three databases on insurgencies, interventions and peacekeeping operations that we have developed. This first was the Modern Contingency Operations Data Base (MCODB) that we developed to use for Bosnia estimate that we did for the Joint Staff in 1995. This is discussed in Appendix II of America’s Modern Wars. It then morphed into the Small Scale Contingency Operations (SSCO) database which we used for the Lighter Weight Army study. We then did the Iraq Casualty Estimate in 2004 and significant part of the SSCO database was then used to create the Modern Insurgency Spread Sheets (MISS). This is all discussed in some depth in my book America’s Modern Wars.

None of these, except the Campaign Data Base and the Battles Data Base (1600-1900), are good for use in a model validation effort. The use of the Campaign Data Base should be supplementary to validation by another database, much like we used it in the Lighter Weight Armor study.

Now, there have been three other major historical validation efforts done that we were not involved in. I will discuss their supporting data on my next post on this subject.

Between 2001 and 2004, TDI undertook a series of studies on the effects of urban combat in cities for the U.S. Army Center for Army Analysis (CAA). These studies examined a total of 304 cases of urban combat at the divisional and battalion level that occurred between 1942 and 2003, as well as 319 cases of concurrent non-urban combat for comparison.

Between 2001 and 2004, TDI undertook a series of studies on the effects of urban combat in cities for the U.S. Army Center for Army Analysis (CAA). These studies examined a total of 304 cases of urban combat at the divisional and battalion level that occurred between 1942 and 2003, as well as 319 cases of concurrent non-urban combat for comparison.