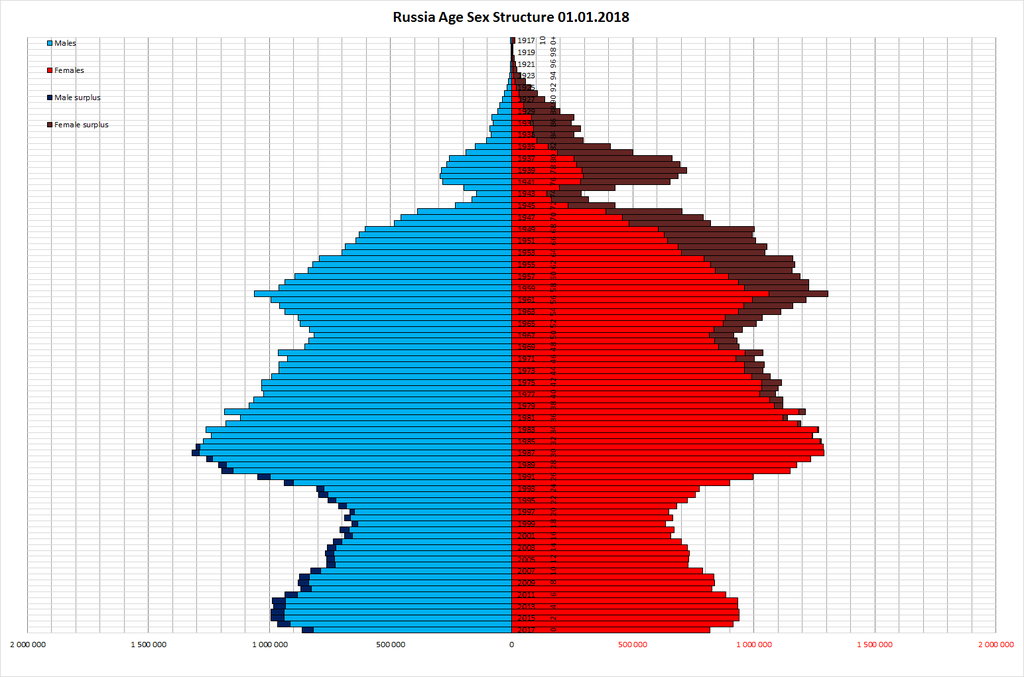

The Soviet Union broke up into 15 separate countries in December 1991. What would a reconstituted Soviet Union/Russian Empire look like, if that is indeed one of the goals of Russian leadership (and some people say it is).

1. Russia, 2. Ukraine, 3. Belarus, 4. Uzbekistan, 5. Kazakhstan, 6. Georgia, 7. Azerbaijan, 8. Lithuania, 9. Moldavia, 10. Latvia, 11, Kirghizia, 12. Tajikistan, 13. Armenia, 14. Turmenistan, 15. Estonia.

The three Baltic states appear to be out of their grasp, being members of NATO. They are militarily protected by an alliance of 29 members, and their economic growth has been significant. The per capita income of Estonia is $19,840 (IMF 2017), while that of Russia is $10,608. Half of Russia’s GDP is in Moscow, just to drive home what the rest of the country is like.

Some of these countries are united into the Eurasian Economic Union. It consists of five countries: Russia, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan. It was Ukrainian President Yanukovych’s decision to develop closer economic ties with Russia and the Eurasian Union and back away from an association agreement with the European Union (28 countries) that started the Euromaiden protests in November 2013 that lead to his removal from power in February 2014 (and the Russian seizure of Crimea and the Russian-influenced revolts in Lugansk and Donetsk). The Eurasian Union flag is below. Interesting map choice.

So who would be in a reconstituted Soviet Union/ Russia Empire?

There are the five “stans” in Central Asia (Kazakstan, Uzbekiskan, Kyrgystan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan). By the nature of their geography they are somewhat isolated, landlocked, and potentially could be brought back into Russia’s orbit. Two countries are already members of the Russian created Eurasian Union. There is also Belarus, another Eurasian Union member. Belarus does not have a strong history of independence and could be brought back into Russia’s orbit. Belarus might very well rejoin Russia after its dictator Lukaschenko (age 64) moves on to wherever he ends up. These could reconstitute a new force if they could be brought into Russia’s orbit. Some stats:

(2018 est.) (IMF 2017)

Population GDP (millions)

Russia 146,877,088 $1,527,469

Uzbekistan 32,653,900 47,883

Kazakhstan 18,292,700 160,839

Belarus 9,478,200 54,436

Tajikistan 8,931,000 7,234

Kyrgystan 6,309,300 7,061

Turkmenistan 5,851,466 37,926

Sub-Total 228,393,654 1,842,848

This adds up. It is more significant demographically than economically. The per capita income of Uzbekistan is $1,491 per year and Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are worse. This recombined country would move from being the 12th richest in the world up to being the 10th richest, ahead of Canada but behind Italy.

Now there are three countries in the Caususus: Georgia, Azerbaijain, and Armenia and four odd political entities (Abkhazia, North Ossetia, Artsakh and Chechnya). Of the three former Soviet countries, Georgia is openly hostile to Russia (and Abkhazia and North Ossetia have been carved from it) and Azerbaijain and Armenia are hostile to each other. They fought a war over the province of Nagorno-Karabakh from 1988-1994, which Armenia won. It is now the Republic of Artsakh.

Only Armenia is a member of the Eurasian Union. It will be difficult for Russia to bring these three nations into its fold for a number of reasons, but again they remain relatively isolated with only Iran and Turkey as the neighbors in the region. So…lets us assume this somehow happens:

Population GDP (millions)

Old Sub-total 228,393,654 1,842,848

Azerbaijain 9,943,226 40,670

Georgia 3,729,600 15,230

Armenia 2,969,800 11,037

Abkhazia 240,705 N/A

Artsakh 145,053 N/A

New sub-total 245,422,038 1,909,785

They are all pretty poor, with Azerbaijan having a per capita income of $4,141 and Georgia and Armenia having similar slightly lower numbers.This really does not get a new Russia Empire back to being a world power. Italy still has a larger GDP.

This now assembles 10 of the original 15 republics together. The three Baltic states are out of reach without a world war, and that leaves only Ukraine and Moldova.

Population GDP

Ukraine 42,248,129 109,321

Moldova 3,550,900 7,945

Transnistria 470,600 N/A

Note that the Ukrainian population figures excludes Crimea and Sevastopol but includes Lugansk and Donetsk. The per capita income of Ukraine is $2,583 and Moldova is $2,280.

It is clear that if one was going to re-constitute the Soviet Union/Russian Empire that Ukraine is the real prize here. Some argue that this is what the conflict in 2013-2014 was about, and is the source of the continued conflict over Crimea, Lugansk and Donetsk.

P.S. The stats for the three Baltic states are:

Population GDP

Lithuania 2,799,127 47,263

Latvia 1,923,400 30,319

Estonia 1,319,133 25,973