Today’s edition of TDI Friday Read asks the question, how do we know if the theories and concepts we use to understand and explain war and warfare accurately depict reality? There is certainly no shortage of explanatory theories available, starting with Sun Tzu in the 6th century BCE and running to the present. As I have mentioned before, all combat models and simulations are theories about how combat works. Military doctrine is also a functional theory of warfare. But how do we know if any of these theories are actually true?

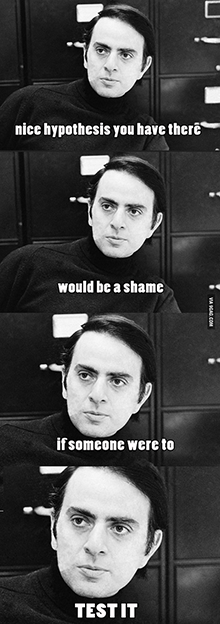

Well, one simple way to find out if a particular theory is valid is to use it to predict the outcome of the phenomenon it purports to explain. Testing theory through prediction is a fundamental aspect of the philosophy of science. If a theory is accurate, it should be able to produce a reasonable accurate prediction of future behavior.

In his 2016 article, “Can We Predict Politics? Toward What End?” Michael D. Ward, a Professor of Political Science at Duke University, made a case for a robust effort for using prediction as a way of evaluating the thicket of theory populating security and strategic studies. Dropping invalid theories and concepts is important, but there is probably more value in figuring out how and why they are wrong.

Trevor Dupuy and TDI publicly put their theories to the test in the form of combat casualty estimates for the 1991 Gulf Way, the U.S. intervention in Bosnia, and the Iraqi insurgency. How well did they do?

Dupuy himself argued passionately for independent testing of combat models against real-world data, a process known as validation. This is actually seldom done in the U.S. military operations research community.

However, TDI has done validation testing of Dupuy’s Quantified Judgement Model (QJM) and Tactical Numerical Deterministic Model (TNDM). The results are available for all to judge.

I will conclude this post on a dissenting note. Trevor Dupuy spent decades arguing for more rigor in the development of combat models and analysis, with only modest success. In fact, he encountered significant skepticism and resistance to his ideas and proposals. To this day, the U.S. Defense Department seems relatively uninterested in evidence-based research on this subject. Why?

David Wilkinson, Editor-in-Chief of the Oxford Review, wrote a fascinating blog post looking at why practitioners seem to have little actual interest in evidence-based practice.

His argument:

The problem with evidence based practice is that outside of areas like health care and aviation/technology is that most people in organisations don’t care about having research evidence for almost anything they do. That doesn’t mean they are not interesting in research but they are just not that interested in using the research to change how they do things – period.

His explanation for why this is and what might be done to remedy the situation is quite interesting.

Happy Holidays to all!