In our previous post, there is an extended discussion on how much the terrain was influencing the results.

Measuring Human Factors based on Casualty Effectiveness in Italy 1943-1944

I have done some analysis of the terrain involved. Below are some figures for the German attacks based upon terrain:

Germans Attacking U.S. – Italian Campaign 1943-44:

…………………………………………..Average..Average

………………………………Percent…Percent…Attacker..Defender

…………………..Cases….Wins…….Advance..Losses…Losses

Rugged Mixed…..1………..0…………..0…………..250……….1617

Rolling Mixed……1…………0…………..0…………..769……….525

Flat Mixed………..3…………0…………33…………..647……….672

.

…………………………………Force….Exchange

…………………..Cases…….Ratio…..Ratio

Rugged Mixed…..1…………..0.72…….0.15-to-1

Rolling Mixed……1…………..0.84…….1.46-to-1

Flat Mixed………..3………….1.60……..0.96-to-1

.

Germans Attacking UK – Italian Campaign 1943-44:

……………………………………………………….Average..Average

………………………………Percent…Percent…Attacker..Defender

…………………..Cases….Wins…….Advance..Losses…Losses

Rugged Mixed…..3……….33…………33…………312……….623

Rolling Mixed…….3………..0…………..0………….250……….689

Flat Mixed…………4………75…………75………….938………755

.

……………………………..Force….Exchange

…………………Cases…..Ratio…..Ratio

Rugged Mixed…..3…………0.82…….0.50-to-1

Rolling Mixed…….3………..0.78…….0.36-to-1

Flat Mixed…………4……….1.38……..1.24-to-1

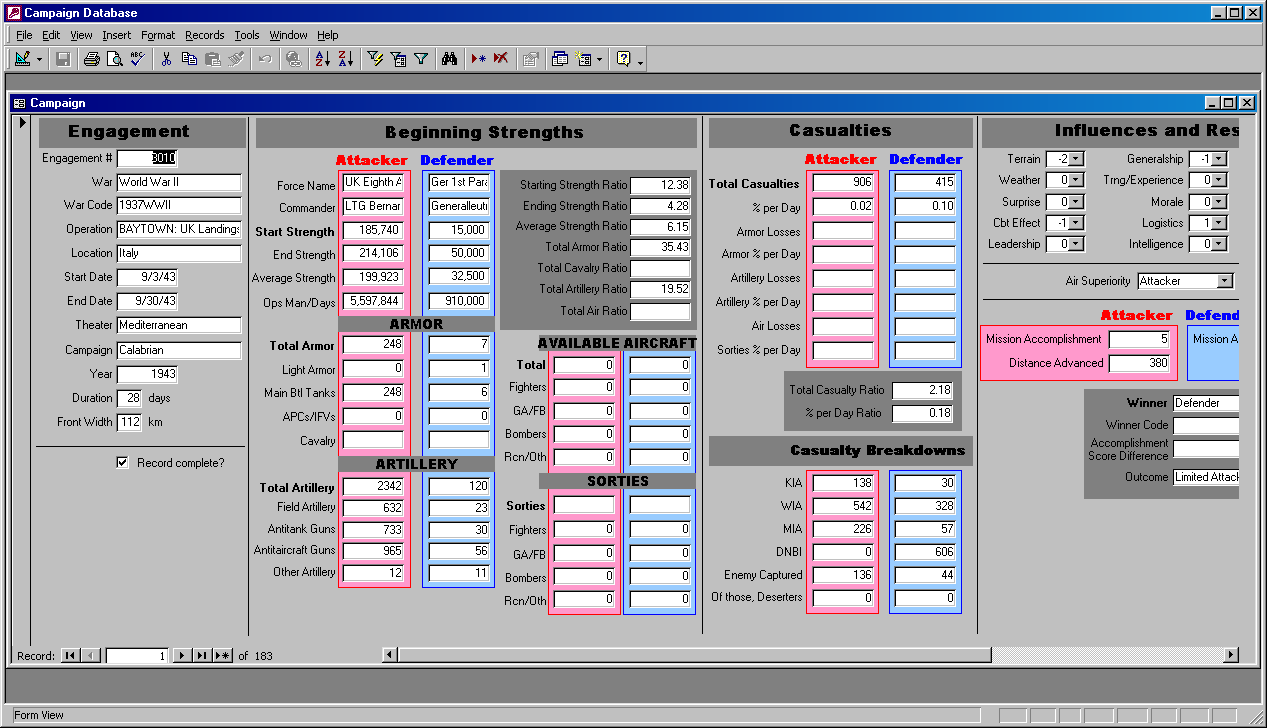

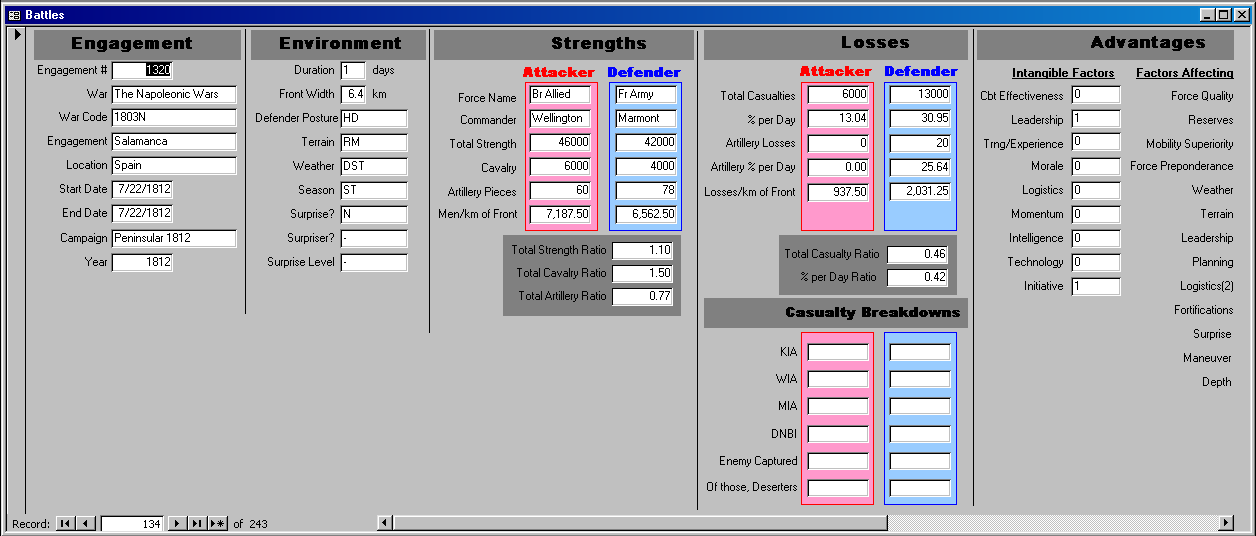

This is material that I am developing for a new book tentatively called More War by Numbers.

Anyhow, the terrain is as defined by Trevor Dupuy. What is interesting to look at is the flat mixed terrain compared to rugged and rolling.

Cases is the number of engagements. Needless to say, the number of cases in each category is way too low to be statistically significant….and this is from a data base of 141 cases (for Italy alone). Percent wins is based upon analyst coding of engagements. Percent advance is based upon a different analyst coding of engagements. In it possible that an engagement can be coded as “Attack Advances” and a “Defender” win. It does not happen in these 15 cases. Average attacker and defender losses is based upon the average losses per day (so losses in a multi-day engagement is divided by the number of days). The force ratio is the total strength of the attackers in all these selected engagements divided by the total strength of the defenders in all these selected engagements. The exchange ratio is the total losses of the attackers in all these selected engagements divided by the total losses of the defender in all these selected engagements.

So, for example, in flat mixed terrain there are three cases of the Germans attacking the Americans. The force ratio is 1.60-to-1 (averaged across these attacks) and the exchange ratio is less than one-to-one (0.96-to-1). On the other hand, in the four cases of the Germans attacking the Americans in flat mixed terrain, the weighted force ratio is 1.38-to-1 and the weighted loss ratio is 1.24-to-1, meaning the German attacker lost more than British defender.

I do have similar data for the Americans. It is also pretty confusing to interpret.