The United States is the third most populous country in the world, and has been since the collapse of the Soviet Union. It is likely to remain the third most populous country for a long time to come, as it will certainly not catch up to the two countries with over a billion people (China and India) and will not be surpassed by anyone else any time soon (Indonesia, 4th on the list, has a population of around 264 million in 2017 and a growth rate of 1.1% compared to the U.S. growth rate of 0.7%). It appears that we will be the third most populous country in the world for decades to come.

The United States population for 2018 is estimated at 328.3 million. This is more than twice what it was in 1950. It has been growing at 9.7% or higher for every decade since 1790, with the exception of the 1930s (7.3% for that decade). Annual growth rate in 2017 is 0.7%.

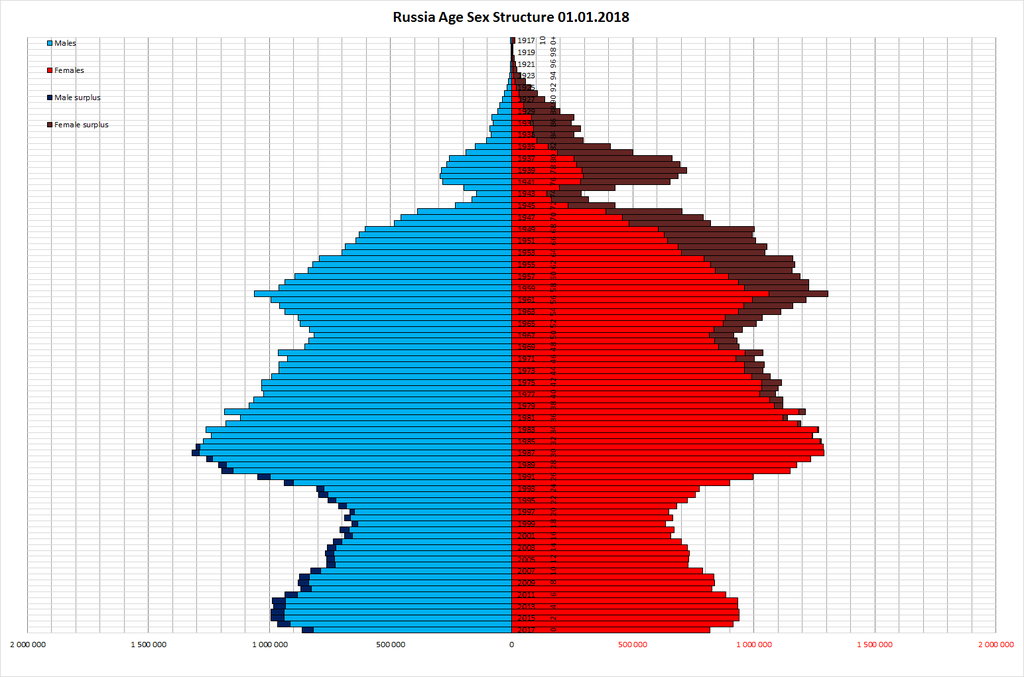

The fertility rates in the U.S. is 1.76 children per woman (2017). This is not that much higher than the 1.61 figure that Russia has (see my previous post on demographics). Almost all developed countries in the world now have a birth rate below 2. It needs to be around 2.1 to achieve replacement rate. The U.S. fertility rate dropped below 2.1 in 1972 and has remained below the replacement rate ever since then, except for two years (2006 and 2007). But, the U.S. population continues to grow, and that growth is due to immigration. If it was not for immigration, the U.S. population would be in decline.

The United States is currently 77.7% “white” (in 2013), which is defined by the census bureau as “having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa.” Non-Hispanic “whites” make up 62.6% of the country’s population. The non-Hispanic “white” population is expected to fall below 50% by 2045. Needless to say, this has become a political issue inside the United States, one that I have no interest in discussing on this blog. See: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2018/03/14/the-us-will-become-minority-white-in-2045-census-projects/

The United Nations predicts the U.S. population will be 402 million in 2050 (compared to their prediction of 132 for Russia in 2050). The U.S. census bureau projects the U.S. population will be 417 million in 2060.

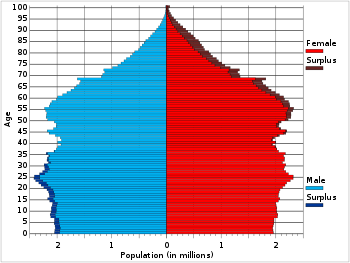

The population has gotten older, with the median age now being 38.1 years. In 1970, at the height of the “youth culture” it was 28.1 years. The demographic “pyramid” from 2015 for the United States is below. This is worth comparing to the Russian “pyramid” in a previous post.

The legal immigration rate of the United States has averaged around 1 million a year from 1989. The legal immigration rate rose to 1.8 million in 1991 and was 1.2 million in 2016. This was very much driven by the Immigration Act of 1990, which raised the cap on immigration. See: https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/yearbook/2016/table1

The illegal immigration rate is harder to calculate, as some illegal immigrants are deported, some return home and I gather a significant number of them later convert to legal immigrants. It is estimated that there are around 11 million illegal immigrants in this country (2016 estimate). In 1990, it was estimated that there were 3.5 million illegal immigrants. Does that mean that the actual immigration rate from illegal immigration is less than 300,000 a year (as many later become legal immigrants)? It is hard to say exactly, but it appears that our immigration rate is somewhere between 1,300,000 and 1,500,000 a year counting both legal and illegal immigrants.

This is the primary source of our population growth and will probably be so for some time to come. The United States ceased reproducing at replacement rate almost 50 years ago. This is not going to change anytime soon. Some immigration is probably essential to maintain our labor force at current or growing levels (this is as close to a political statement as I am going to get on the subject).

Next to China, India, Japan and Germany.

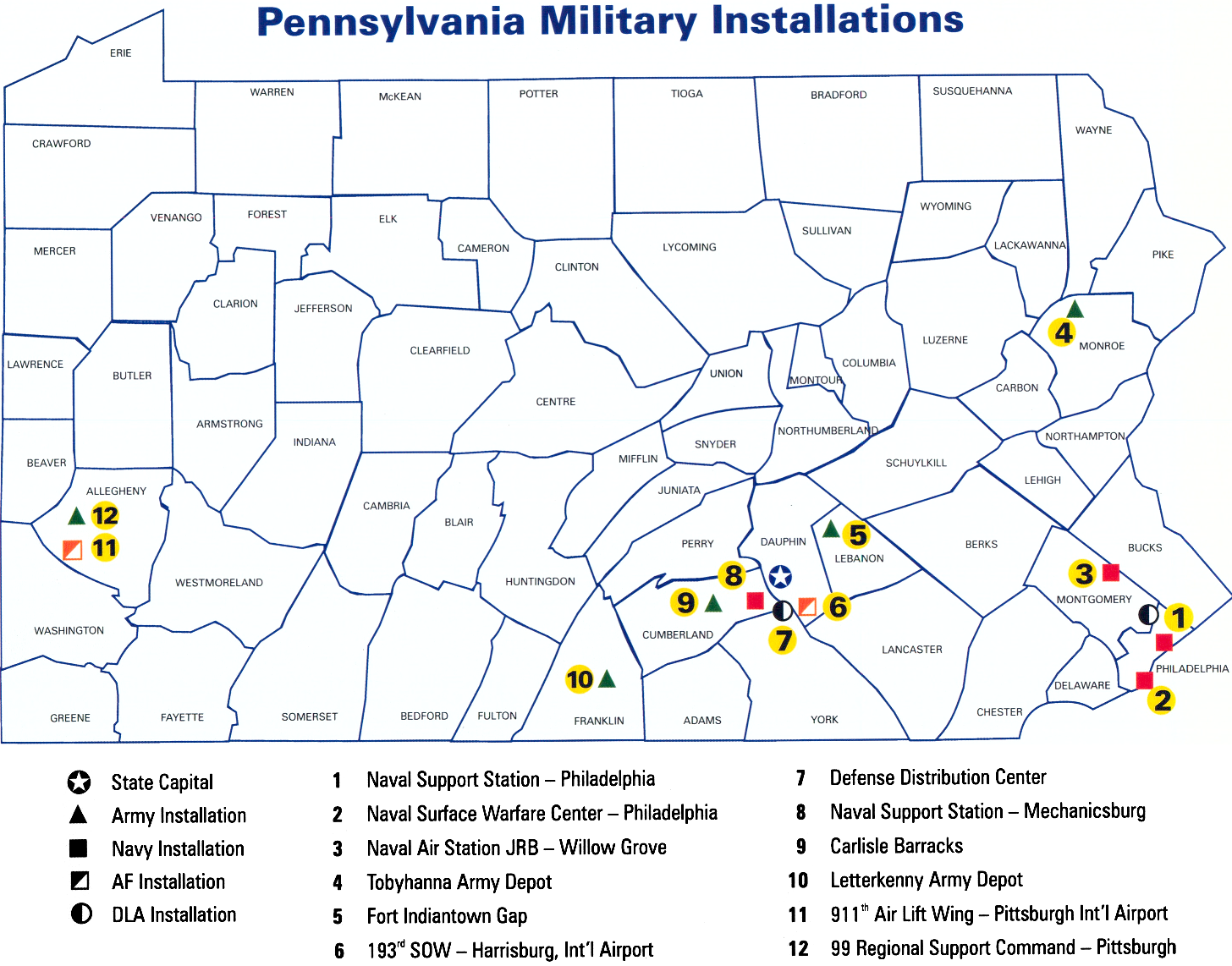

This map is from 2003.

This map is from 2003.